By Bob Rietz

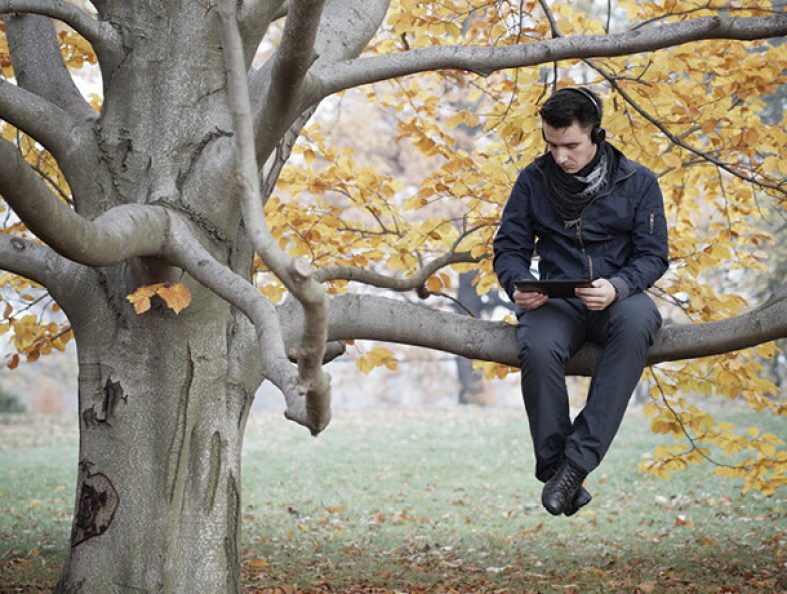

We’ve all been out on a limb—that is, we have taken a risk. Our first kiss, our first date. We weighed the risk of rejection, and decided the possible reward was worth taking the risk. Then the risks and rewards became bigger. Marriage. Will they say yes? What if they reject me? Should I accept? Do I want to spend the rest of my life with this person?

Selecting an occupation was another risk and reward choice. This math major chose between becoming a teacher and an actuary. A teaching career presented little to no risk but low lifetime earnings potential. Trying to become an actuary carried a high risk—exam pass ratios were hovering around 40%—but also promised rewards of high career earnings. Readers will think the rewards exceeded the risks, but they represent survivor bias. What about others who also took the risk but weren’t able to successfully pass through the exam gantlet?

I think back to my first house. How far out on a limb did I crawl, promising to pay $180/month, about 20% of my take-home pay, for 30 years? (1972 was a very long time ago.)

Children were another consideration. Can we afford to feed, clothe, shelter, educate, and nurture another human being? And another? And one more? Who took the greater risk, the parent or the child?

Relocation, whether while working or after retirement, represents a classic risk and reward analysis. Moving often means trading the security of family, friends, and established personal infrastructure for the lure of better climate, lower taxes, and superior cultural or natural attractions. Thank goodness for healthy trees with sturdy limbs!

Few people spend their entire working lifetime with their first employer. At some point, everyone measures the risk of changing employers or occupations against the rewards. An unfamiliar workplace, different co-workers, and expectations of a new supervisor present nebulous risks to evaluate. Potential rewards of higher salary, professional advancement, and job satisfaction can be as difficult to appraise.

Retirement provides another occasion to gauge risks and rewards. The primary risk is outliving an income stream. Another risk is living too economically, and not enjoying the fruits of a lifetime of labor. Conversely, rewards appear bountiful; who doesn’t dream of endless golf, travel, reading, volunteering? The list goes on and on. Yet retirement is not an easy risk/reward decision. Retirement was the topic of the author’s initial End Paper column (“The Hardest Thing I Ever Did”; Contingencies; Sept./Oct. 2010).

Trees and limbs still beckon, even in retirement. The Cottons of Grundisburgh was my first attempt at writing more than 725 words (see “Who’s Your (Daddy’s Daddy’s) Daddy?”; Contingencies; Sept./Oct. 2020). The book has been available online since late May, with total sales in the low double digits. Did I feel a limb snap?

I’m on another limb and hope this one is stronger, because I’m spending three or four hours a day on it. My longsuffering wife says I’m obsessed … and she usually has a more accurate perspective than I do. This limb started with a long lost family relic I found during a pandemic-inspired spring cleaning. Tucked inside my mother’s wedding album were 25 single-spaced yellowed typewritten pages.

My aunt was a Maryknoll missionary; her first assignment was in mainland China in early 1949. She was 28 and proselytized with one other Maryknoll missionary in and around Xingning, a village with 4,000 inhabitants.

The Korean War commenced on June 25, 1950, and after almost being annihilated at Pusan, the U.S. military counterattacked and advanced within 50 miles of the Chinese border. Which is when she was placed under house arrest for 13 months with rations of rice, lard, and salt. She endured multiple searches of the convent, was falsely convicted of spying in a People’s Trial, and witnessed executions. Edith smuggled the 25 pages through numerous border inspections when China expelled her in January 1952.

Her story needs to be shouted from the rooftops. A 60,000- to 70,000-word novel, based primarily on these typewritten pages, is about halfway completed. Finding a literary agent willing to represent a debut author to publishing houses will be the next step in the process. If this limb breaks at that point, the public will never learn of this strong woman, and about 2,000 hours will be for naught.

Stay tuned.

BOB RIETZ is a retired pension actuary who lives in Asheville, N.C. His book, The Cottons of Grundisburgh, relating his forays into genealogy back to a small village in Suffolk, England, was published in March.