By Carlos Fuentes

The Strategic Role of Ownership

Structure for Insurance Companies

“All men can see these tactics whereby I conquer, but what none can see is the strategy out of which victory is evolved”

—Sun Tzu

What is the corporate structure that best supports an entity’s goals? Private? Not-for-profit? Managed by the government? It is difficult to imagine an automobile manufacturer organized as a non-for-profit company, yet there are accomplished cooperatives such as the Mexican cement enterprise Cruz Azul. In education, state and not-for-profit universities have been successful while for-profit institutions have not. In the provision of health care, when the U.S. model is compared with the models of other industrialized countries, the evidence is overwhelmingly clear, yet there is much disagreement on the subject. What about insurance companies? Are stock companies (“stocks”) the obvious choice? Or maybe there are reasons to believe that mutual companies (“mutuals”) are better positioned for success?

This article discusses the role of ownership structure in insurance companies from a strategic point of view. The reader who is unfamiliar with game theory will find a brief discussion of concepts utilized in this article such as Nash Equilibrium in “Winning or Losing the Game,” Contingencies, July/August 2016.

Executive Summary

“Go for a business that any idiot can run because sooner or later any idiot probably is going to run it”

—Peter Lynch

The mutual form of ownership, although declining, has been conspicuous in the insurance industry. Its early success was based on the mutuals’ ability to select better risks, make credible commitments to solvency and product value, and align owners’ and customers’ interests. With the passage of time, these advantages have become less accentuated: Solvency regulation applies to all insurers, making them roughly equivalent in their ability to fulfill future obligations; technology has allowed stocks to improve their risk selection abilities and product offerings; the image of mutuals has changed from that of a small company formed to serve the community to a big corporation with as much or little sense of social responsibility as stocks. On the other hand, competitive forces have fueled mergers and acquisitions as insurers seek to take advantage

of economies of scale,[1] economies of scope,[2] and complementarities,[3] transactions for which the mutual ownership model places insurers at a disadvantage over their stock counterparts. It is not surprising, then, that mutuals are converting to enjoy the same structural flexibility.

Company Structure

“A good system shortens the road to the goal”

—Orison Swett Marden

Insurance firms can be structured as stock, mutual, or non-for-profit companies. A mutual company is a corporation that has no shareholders. Instead, policyholders, as long as they remain alive and keep their policies in force, have the following membership rights:

- Contractual benefits, which vary depending on the policy in force (e.g., life insurance protection and dividend payments for a whole life insurance product);

- The assurance that the corporation operates primarily for the benefit of its members;

- The right of participating in corporate governance, usually by electing directors to oversee the operation of the company;

- The entitlement to bring legal action against the directors and officers for violating their fiduciary duties;

- Receipt of any remaining value if the corporation is liquidated or demutualized.

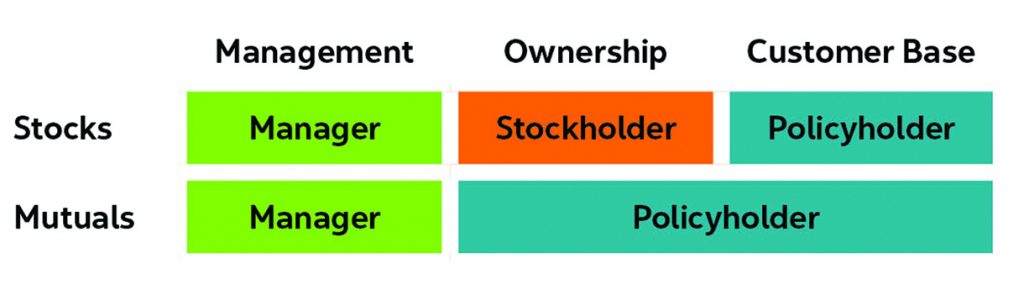

A stock company is a corporation that serves customers (policyholders) who have no ownership rights or interests in the enterprise. Subject to a fair amount of regulation, the company operates for the benefit of its shareholders.

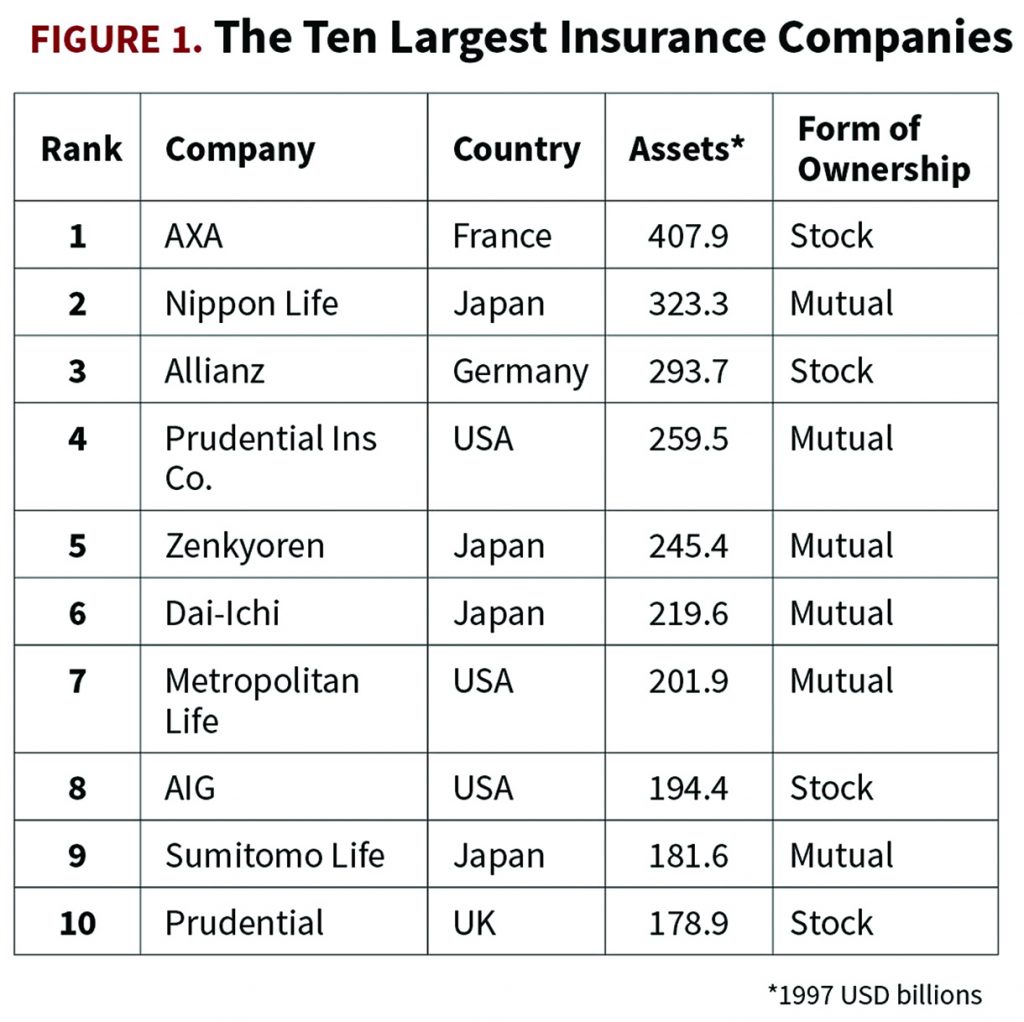

In 1997, six of the 10 largest insurance companies in the world were mutuals (See Figure 1).[4]

Although the prevalence of mutual ownership varies widely by country, mutuals have played a significant role in international insurance business. Their presence, however, has decreased over the past decades due to conversions to stock ownership triggered by two forces: competition and consolidation.

The Reasons Behind Demutualization

“Only the extremely wise and the extremely stupid do not change”

Competition

The old model under which mutuals enjoyed the advantages of strong horizontal differentiation[5] (via local recognition) and substantial market share penetration has been transformed with the advent of technological advances (e.g., internet services, efficient mass marketing) that reduce search costs and allow insurers to serve customers regardless of place of residence. Furthermore, consumer tastes have changed, rendering typical mutual products less appealing and forcing insurers to continuously innovate. In the life/pension arena, for example, the emphasis has shifted from saving to investing products; in the health arena, from indemnity to complex managed care to pay-for-performance and investment accounts. This alteration in demand has prompted many insurers to develop or purchase asset management tools, expand the scope of their horizontal boundaries,[6] and consider options for enlarging their geographical reach. Companies wishing to compete must make extensive technological investments that mutuals sometimes cannot afford.

To summarize, technology has reduced entry barriers in what once were niche markets for mutual insurers while at the same time shifts in consumer demands have increased the need for capital investments, an activity in which mutuals are at a disadvantage compared with their stock-structured counterparts.

Consolidation

In reaction to competitive forces, more and more insurers are merging with one another and with other types of financial service providers as they see opportunities for complementarities, economies of scale and economies of scope. The argument for complementarities, typically elusive, is better understood with an example: an investment bank could acquire a life insurance company with a large pension portfolio, giving rise to the following opportunities for improvement:

- Fund managers would enjoy added financial latitude in their investment decisions as the matching of assets and liabilities could be integrated or fragmented, subject to company needs and regulation;

- The pool of specific human assets, particularly actuarial and investment talent, would be enlarged and perhaps diversified;

- The good reputation and strong brand recognition of the acquirer or acquired entity could result in umbrella branding.[7]

Economies of scale are expected to translate into lower unit costs achieved mainly through reduced overhead and enhanced distribution channels.[8] Economies of scope are expected to result in the introduction of new financial products (a key advantage in a dynamic, growing industry) and cross-selling, which increases revenue and decreases lapse rates.

The strategic importance of consolidation has been fueled by record-high stock prices (the percentage of insurance acquisitions that funded entirely with cash decreased sharply in recent years[9]), deregulation and, in Europe, the introduction of the euro. But consolidations and acquisitions are much more difficult transactions for mutual insurers,[10] which must rely entirely on retained earnings and debt financing.

In the U.S., a more liberal regulatory stance has softened banks’ entry barriers into the insurance market; in Europe, the focus of insurance supervision has shifted from regulating rates to preventing insolvencies, also lowering entry barriers. Proactive insurers can seize new opportunities by expanding their business into markets and activities that were previously off-limits. Insurers that do not react run the risk of falling out of step with a rapidly changing market. Mutuals are at a competitive disadvantage to expand, merge, or acquire due in part to the stringent regulation in which they operate.

The adoption of the euro paved the way for a unified European capital market that is much broader and deeper than the capital markets of any individual European country. The resulting expansion in the scope of investments from a national to a pan-European scale has increased the demands on asset managers and fueled diversifications.

Does It Make Sense to Go From Stock to Mutual Status?

“The best advice will come from the person who has no personal interest in the matter”

—Eraldo Banovac

The wave of demutualizations has been a response to market conditions, which could change—making the mutual ownership model attractive again. For example, stock companies may want to mutualize to avoid being acquired. Furthermore, the possibility of stock companies not controlling the customer-owner conflict to the satisfaction of regulators could also trigger mutualizations, as it happened in the early part of the 20th century when the Armstrong Commission,[11] after finding evidence of outrageous abuses within the industry, recommended—and the state of New York adopted—the statute that allows stock companies to convert to the mutual form. Sequels of that event have been long-lasting; for example, in 1978, Richard Schinn, the chief executive of Metropolitan Life (a company that mutualized in 1915) stated before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Citizens and Shareholder Rights and Remedies[12] that “no longer would the board be subject to the conflicting interest of shareholders and policyholders—their primary responsibility would now be to the policyholders. … Let me emphasize that Metropolitan’s conversion to a mutual company benefited the policyholders by insulating them from possible attempts to raid the large pools of marketable assets, representing policy reserves and surplus.”

The Absence of Shareholders Provides Mutuals With a Pricing Advantage[13]

“Any fool can know. The point is to understand”

—Albert Einstein

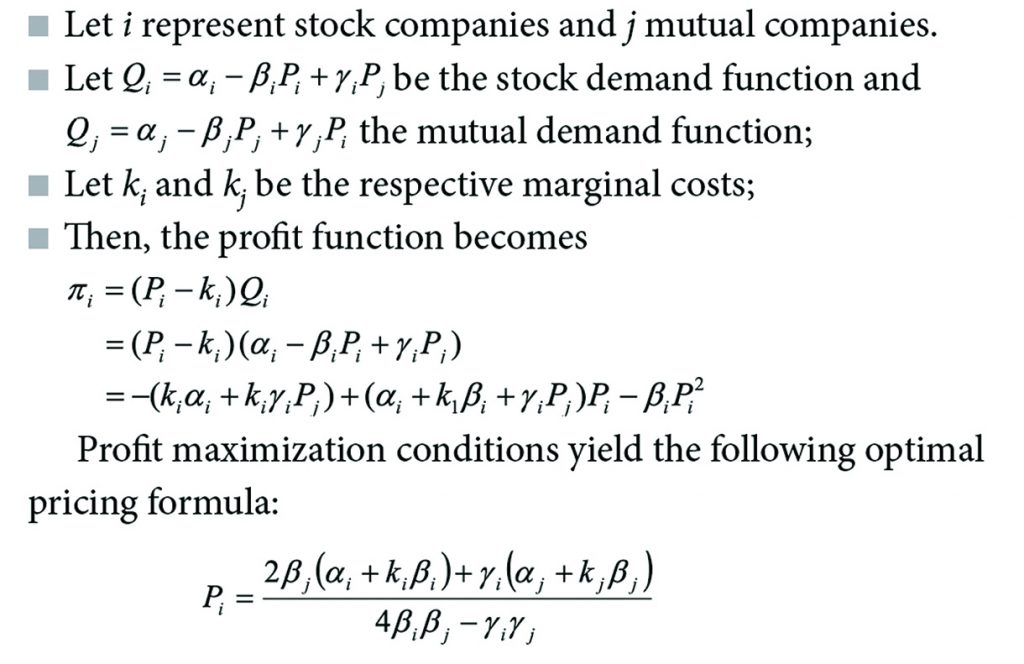

This is a key consideration and a reminder that lower prices do not necessarily translate into optimal profits. To analyze the pricing dynamics of mutuals and stocks, note that it is reasonable to think of mutuals and stocks as oligopolistic companies engaged in a Differentiated Bertrand[14] Competition,[15] either locally, nationally, or internationally. The economic model is as follows:

Finding the values of the parameters requires an econometric study that is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is reasonable to speculate that demand at the local level was initially greater for mutuals than for stocks and that, over time, it has been equalized by the forces described above. Marginal costs—defined in this case as the expenses incurred by the firm to provide services, including distribution costs, the cost of capital (e.g., dividend payments to shareholders) and agency costs—are higher for stocks,[16] that is, ki > kj.

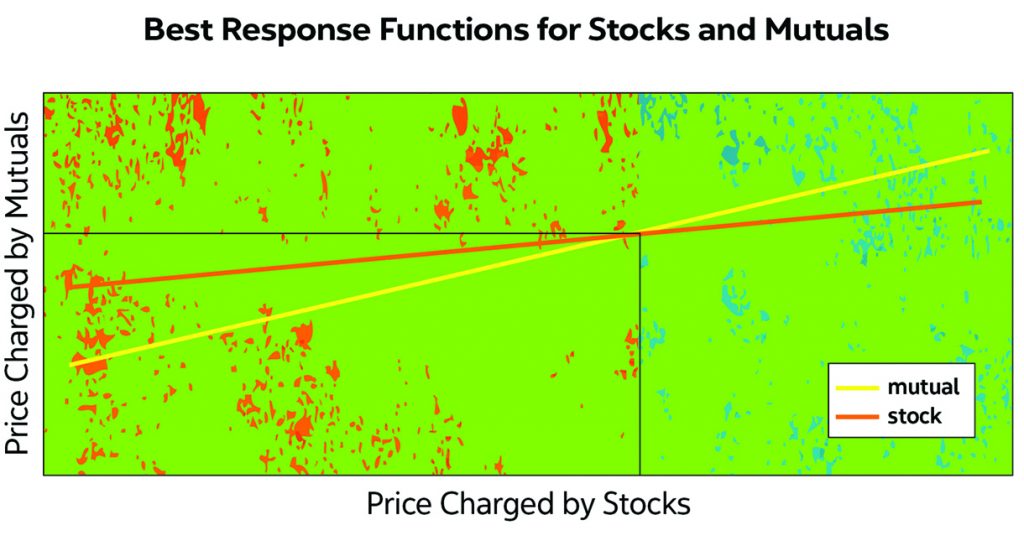

In this scenario, the Nash equilibrium is such that the price charged by mutuals is slightly lower than the price charged by stocks for the same product. This result is consistent with the lower cost coverage provided by mutuals, typically expressed in actuarial terms as higher loss ratios.

With the introduction of new products, cross-selling, and integration of banking and insurance services, the demand for stock products exceeded the demand for mutual products. The Differentiated Bertrand Model indicates that in this scenario, the Nash equilibrium is such that the price gap between stocks and mutuals widens, with mutuals reducing premium rates (or not increasing rates as much as stocks) to defend market share, and stocks increasing premium rates to maximize profits. This tendency would be less apparent in offerings that do not enjoy a great deal of horizontal differentiation such as medical policies, but even in the health care sector, companies continue to develop products with unique features.[17]

Countering the pricing effects of stock products are the efforts of stocks to become more efficient, particularly regarding distribution channels.[18] If stocks manage to reduce marginal costs—that is, if the difference between ki and kj shrinks—then the prices charged (or the rate increases) by both stocks and mutuals would decrease (more so for stocks), but the amount of insurance sold would increase (more so for stocks), resulting in more profits for stocks and less for mutuals. Regardless of price changes, stocks would adopt a long-run marginal strategy (i.e., expense reduction) due to their commitments to shareholders. Shadow pricing,[19] popular with health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and very much a U.S. phenomenon, is unlikely to play a role in the current insurance environment.

Agency Theory and the Ownership Structure of insurance Companies

“See through the stereotypes, which were made due to lack of information”

—Richard Burr

It is interesting to point out that in 1997, the three largest American mutual insurers (Prudential, Metropolitan Life, and State Farm) together had more assets than any industrial corporation in the U.S. except for General Motors, Ford, and General Electric. Does this mean that mutuals have been as efficient as stock companies? If so, how have they been able to overcome their corporate structural disadvantages that seem so daunting?

When attempting to measure efficiency, actuaries typically focus on production costs, which include direct costs (e.g., reimbursement to hospitals in the case of health insurance) and indirect costs (e.g., staff salaries). Like other financial professionals, actuaries believe that mutuals and not-for-profits are less efficient than stock insurers. Their opinion, validated by numerous studies, conforms to economic thinking.[20] However, mutuals can be—and in some cases have been—at least as efficient as stock companies despite their higher production costs. Agency theory[21] can explain this apparent contradiction: Firms that successfully compete have ownership structures that help them minimize total costs, which are the sum of production costs and agency costs. Production costs have been the subject of numerous studies and are the typical basis for assessing efficiency. Agency costs, on the other hand, are a relatively new development in economics and are not as well known in actuarial literature.

Agency costs arise from conflicting incentives within an organization and are defined as the sum of the expenses for reducing conflicts plus the value of output lost by not eliminating them. To understand the conflicts that arise in the insurance industry, note first that mutual and stock companies have different stakeholders: managers and owners (policyholders) for mutuals; managers, stockholders, and policyholders for stock companies.

The Customer-Owner Conflict

The management of a stock insurer sets dividend, financing, and investment policies in ways that benefit stockholders at the expense of policyholders. On the other hand, the management of a mutual insurer has the flexibility to undertake initiatives in the long-term interest of policyholders that may not bear fruit initially. The mutual form of ownership mitigates the customer-owner conflict by merging the owner and customer functions, thus minimizing policyholder subsidies to shareholders. A major rating agency noted this potential for conflict: “Moody’s believes that mutual life insurers that change their corporate form [from mutual to stock] are likely to become more focused on increasing their return on equity and improving shareholder returns, and that this focus will often cause a reduction in creditworthiness.”[22, 23]

The Owner-Manager Conflict

The separation of ownership and control raises concerns about the extent to which management might pursue its own interests at the expense of the owners of the firm. The ownership form of an insurer can either mitigate or aggravate the owner-management conflict. If an insurer is a publicly traded stock company, its management must concern itself with the performance of the stock. Mutual insurers, by contrast, cannot issue stock or options to align managers’ and owners’ interests.[24] Most policyholders lack financial awareness and have no convenient way of assessing how well their mutual is managed; thus, management faces no effective market for corporate control.

To summarize, mutual ownership is more effective in controlling the customer-owner conflict and less effective in controlling the owner-manager conflict. These costs are difficult to assess but significant.

Agency Theory and the Existence of Mutual Insurance Companies[25]

European life mutuals have their roots in the Middle Ages when guilds protected members and their families in the event of sickness or death.[26] After the guilds disbanded, member protection continued through the establishment of mutual insurers that, by virtue of their ownership structure, could make commitments of financial stability and concern for their policyholders.[27] In the U.S., the insurance industry’s early history is plagued with examples where mutuals succeeded while stocks did not, as stocks could not make credible commitments on solvency matters, and consequently were relegated to offering only term life insurance for short time horizons (one to seven years). In short, the mutual ownership structure decreases the probability of insolvency by minimizing management’s incentives to behave opportunistically through low claims reserves[28] or aggressive investments, and by giving managers latitude to set adequate premia. Oddly enough, by constraining the behavior of managers and setting solvency standards, regulation improved the credibility of stock insurers, thereby slowly leveling off the playing field.[29, 30]

In contrast to life insurance, solvency considerations are less relevant in property/casualty, where policies are in force for short durations.[31] The early advantage of mutuals was due to superior underwriting information (i.e., minimization of the asymmetric applicant-underwriter information problem[32]) and reduced moral risk,[33] both the result of the ownership structure. Mutuals, which were started by groups of people or businesses in a given region or industry, had as customers policyholders who were less likely to cheat peers than to defraud stock companies. Furthermore, mutuals often possessed clearer insights into local risk identification and assessment than remotely located stock insurers.

The Managerial Discretion Hypothesis

Mayers and Smith developed the managerial discretion hypothesis,[34] which rests on the agency theory. The managerial discretion hypothesis states that mutuals tend to specialize in lines of business where management has limited discretion to compensate for the limited control that owners exercise over management. Empirical research on the U.S. property/casualty market confirms that this is the case. Research also shows that stocks tended to operate on a more geographically diverse basis than did mutuals (geographic diversity requires greater managerial discretion with regard to resource allocation and similar issues). Thus, ownership structure influences market positioning in terms of product offerings and geographic reach.

The Evidence

Lamm-Tennant and Starks examine the risks underwritten by U.S. property/casualty insurers.[35] They find that, controlling for firm size, the loss ratios of stocks vary more than the loss ratios of mutuals, and that mutuals concentrate in homeowners’ multiple peril, automotive liability, and automotive physical damage, while stocks concentrate in workers’ compensation and other liabilities. In particular, mutuals have been most conspicuous in automotive lines, which have low underwriting risk and therefore require limited managerial discretion. In the health/life market, mutuals have been most active in health lines and in the provision of ordinary life products such a whole life insurance and endowments. In the U.S. pension business, mutuals were late adopters of in-house asset management capabilities, which were crucial for entering the rapidly growing annuity business. These findings are consistent with agency theory and the managerial discretion theory and support the following conclusion: Mutuals have less incentive to direct their attention to riskier lines of business.

In terms of operational efficiency, loss ratios and cost ratios[36] are the most revealing metrics, although loss ratios are less informative due to the long-term nature of the contracts and the difficulty in assessing the performance of the savings component. Typical financial measures such as return on investment provide a distorted view because mutuals offer lower cost coverage to members and naturally underperform when measured in terms of earnings.[37] As expected, property/casualty and health mutuals have had higher loss ratios than stock insurers; surprisingly, however, mutuals have had lower cost ratios. This result may be partly due to the use by mutuals of more efficient distribution channels and their ability to better control agency costs, which remain elusive but can be substantial. In the life segment, the cost ratios of mutuals and stocks have been roughly the same, although there are variations by field of specialty.

Final Remarks

“We are surrounded by data but starved for insights”

—Jay Baer

The corporate structure of insurers furthers or hinders their competitive position depending on the prevailing economic, technological, and legal environment in which they operate. Mutuals enjoyed advantages over stocks such as better risk selection, a high-level of credibility with the public, alignment of owner and customer incentives and, in the absence of shareholders, better value to customers. With the passage of time, the playing field for mutuals and stocks has leveled off while access to capital—indispensable for growth and acquisitions—has become the paramount consideration. Current market conditions favor stocks over mutuals, hence the wave toward conversion. Despite this, mutuals have been able to compete successfully with stocks and their share of the worldwide insurance market remains substantial.

The strategic analysis of the ownership structure of an insurance company sheds light into topics such as pricing and management incentives. Although technical studies tend to downplay the latter, human nature—sometimes in glaring display but more often buried in piles of financial studies—is the driving force behind the dynamics of any financial institution, including insurance companies. Game theory, which can be learned, and intuition, which can be improved, enhance the likelihood of understanding complex dynamics and making better decisions.

Carlos Fuentes, MAAA, FSA, FCA, MBA, is president of Axiom Actuarial Consulting and managing partner of Your2tor.

The opinions expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author. They do not express the official views of the American Academy of Actuaries, nor do they necessarily reflect the opinions of the Academy’s officers, members, or staff.

References

[1] Economies of scale are cost advantages reaped by companies when production is increased and costs are reduced. [2] Economies of scope refers to the reduction of per-unit costs through the production of a wider variety of goods or services. [3] A complementary service is a service whose use is related to the use of an associated service. Two services (A and B) are complementary if using more of service A requires using more of service B. [4] Source: “Special Report: World Business,” The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 28, 2006. [5] Horizontal differentiation refers to differences between products that increase perceived benefit for some consumers but decrease it for others. For example, the same automobile can be offered with automatic or manual transmission. Vertical differentiation refers to features of a product that makes it better than the products of competition. For example, the higher resolution of a monitor, the more desirable it is. [6] A firm’s horizontal boundaries identify the quantities and varieties of products and services that it produces. [7] Umbrella branding is the marketing practice of selling several related products under a single brand. [8] One of the competitive advantages of mutuals over stocks has been their more efficient distribution channels. [9] From over 70% in 1993 to under 40% in 1998—and the trend has continued. See Fox-Pitt, Kelton, “Corporate Finance Outlook: Mutual Insurance Companies,” October 1998, p. 3. [10] Other factors may trigger demutualizations: mutual company executives are richly rewarded when an insurer goes public. Furthermore, reorganizations benefit investment bankers, attorneys, accountants, and consulting actuaries whose professional services are required to implement the demutualization. [11] In the early 20th century, public outrage at certain life insurance practices led to an investigation in New York state that threatened to curtail growth in the industry. Charles Evans Hughes guided the four-month-long Armstrong Investigation, which made startling revelations, and offered a number of controversial recommendations, several of which would forbid the most popular form of life insurance (tontine insurance), limit the growth of life insurers (which included several of the nation’s largest financial institutions at the time), and prevent insurance firms from owning the stock of other companies. [12] New York State Assembly Standing Committee on Insurance, “The Feeling’s Not Mutual: An Analysis of Governor Pataki’s Proposed Mutual Holding Company Legislation,” March 1998. [13] See Stephen Paul Taylor-Gooby of Tillinghast-Towers Perrin, “Demutualization in an International Context,” Society of Actuaries, Record 24:1 (June 1998). [14] Joseph Louis Francois Bertrand (1822–1900) was a French mathematician who worked in the fields of number theory, differential geometry, probability, thermodynamics, and economics. [15] In a Bertrand’s model, each firm selects a price to maximize its own profits, given the price that it believes the other firm will select. [16] Other costs (such provider reimbursement, which depend on negotiated discounts) are assumed to be independent of the company’s ownership structure. For purposes of the present discussion, a sweeping cost hypothesis is necessary. [17] Unique features may include services targeted to specific populations (e.g., acupuncture for Chinese customers), marketing material in a language other than English, contracting with certain group of providers (e.g., Spanish-speaking doctors), wellness programs, etc. This dynamic is conspicuous in the private Medicare segment. [18] For example, in the U.S. not-for-profit Blue Cross Blue Shield plans have sold their products through captive agents. Stocks have relied on brokers and general agents, who tend to be more expensive. [19] Shadow pricing is the practice of maintaining price parity with competitors while profiting from a low-cost structure, rather than profiting from a greater market share. [20] Market discipline forces stock companies to minimize production costs. [21] Agency theory attempts to explain the manner in which businesses are organized and how managers behave. See Michael C. Jensen and William H. Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 3:305-60 (October 1976), and J. Zimmerman, Accounting for Decision Making and Control (2006), pp. 156-163. [22] Arthur Fliegelman, Kevin W. Maloney, and Robert L. Riegel, “March of the Mutuals—A Rapidly Evolving World,” Moody’s Investors Service, May 1998. [23] The promise to fulfill contractual obligations is part of the insurance product. When this obligation is impaired, the value of the product diminishes. [24] Although mutual insurers can and do pay performance-linked bonuses, these have tended to be more modest than the stock and options packages that stock companies pay their executives. [25] For an extended discussion, see “The Ownership of Enterprise” by Henry Hansmann. [26] Two important examples of these early mutuals were the German Wandsbeker Kranken-und Totenlade, established in 1677, and the British Amicable Society for Perpetual Assurance Office, founded in 1706. [27] Credibility was crucial in light of the risks associated with long-term insurance contracts. [28] In fact, claims reserves is one of the few places where not-for-profits and mutuals can “discreetly” accumulate surplus. [29] Despite regulatory oversight, many early U.S. stock companies were quite unstable. Sixty percent of the stock companies operating in 1868 had failed by 1905. [30] The strategic importance of commitments cannot be overstated. Mutuals, by virtue of their ownership structure, were committed to serve their customers who were also owners. Stocks were committed to their stockholders first, then to their management teams, and finally to their customers. Regulation forced stocks to act with a minimum level of responsibility toward their customers, thereby extracting a “commitment” that, although different in nature from the early commitments of mutuals, had the effect of rendering claims on solvency credible. [31] There are exceptions, of course, such as workers’ compensation medical insurance. [32] In contract theory and economics, information asymmetry is the study of decisions in transactions where one party is more informed than the other. [33] Moral risk or moral hazard refers to situations in which an economic actor has an incentive to increase its exposure to risk because it does not bear the full costs of that risk. For example, a bank could issue risky loans to increase earning (because they pay a high interest rate) if it knows that in case of default, taxpayers—not management—will front the bill. [34] “Ownership Structure Across Lines of Property Casualty Insurance,” David Mayers and Clifford W. Smith, Jr., Journal of Economics 31: 351-78 (1988). [35] “Stock versus Mutual Ownership Structures: The Risk Implication,” Joan Lamm-Tennant and Laura T. Starks, Journal of Business 66:29-46 (1993). [36] Keeping other variables constant, the higher the loss ratios, the larger the shares of premiums that flow back to policyholders in form of lower payments. Higher loss ratios, on the other hand, could reflect weaker underwriting standards. The lower the cost ratio, the greater the insurer’s operating efficiency. [37] Mutuals are typically subject to higher solvency standards, which also depress return-on-equity measures. Additionally, the risk profile and the corresponding expected returns of the businesses that mutuals and stocks underwrite are different. When a mutual plans to convert, however, management shifts its focus from servicing customers to maximizing profits.