Though addiction and overdoses remain a major problem, one avenue of abuse has been cleaned up

By Jim Lynch

Eight years ago, I wrote in these pages about an epidemic of prescription drug abuse and how doctors, hospitals, insurers, and regulators were responding. I focused on workers’ compensation insurance because that is what I know best.

How have things gone since then? For workers’ comp, not bad.

When injured workers receive opioids, they get fewer pills, and, on average, each pill is weaker. Alternative treatments—for example, less-addictive drugs, physical therapy, massage—are used more often. And the number of deaths from prescription drugs nationwide has leveled off. Workers’ compensation insurers spend less on opioids, and the number of addicts created by the medical community has fallen, too.

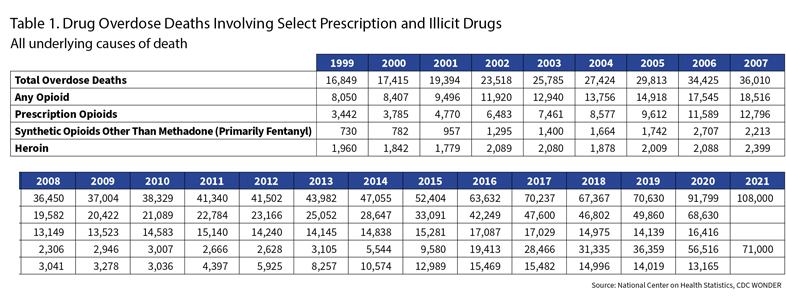

The prescription drug crisis has been blunted. But the abuse of drugs has gotten so much worse. Look at Table 1. More than 100,000 people died from overdoses last year, twice as many as eight years ago.

To be realistic, there is only so much that workers’ comp can do. As a specialized twist on medical care—patients are employees hurt on the job—workers’ compensation has a number of advantages and disadvantages in dealing with a health care crisis.

The disadvantages are easy to see. It lacks some of the tools that other lines of business use to control costs. The worker pays no deductibles and no co-payments. The amount ultimately paid is often unlimited.

An advantage: Benefits are defined by statute. And it is required for almost all businesses. For many, it is their most expensive insurance purchase. That means insurers, businesses, and unions can confront legislators and regulators when the system is suffering.

The workers’ comp tools are designed to restrain costs. They aren’t directly designed to prevent a problem like addiction. But if you prescribe less often and you prescribe smaller amounts, you not only save money, your work is often consistent with the goal of preventing addiction.

So, thanks to a lot of stakeholders—including workers’ comp—there has been progress, but it continues to be a long road … one that begins with a tiny drug company on the island of Manhattan.

Until the late 1970s, Purdue Frederick was a fairly small pharmaceutical firm perhaps best known as maker of Senokot, a stool softener. Its fortunes changed when a British subsidiary called Napp developed a special painkiller called MS Contin.

MS Contin was a morphine pill, a fact that is worrisome all by itself. The medical world—heck, the whole world—has for centuries been tempted by and wary of morphine and its brethren, the most infamous of which is heroin. Heroin and morphine are opiates. Opiates deaden pain. They also create a sense of well-being; anxiety and depression recede. The euphoria is followed by a devastating crash.

After the cycle, the user craves another dose—to escape the crash and embrace another high. Compounding the matter, the body becomes more tolerant of the drug. You need a bigger dose to get the same high. If you stop taking the drug, the body goes through withdrawal; you need more and more of the drug, but the body won’t let you stop. An excessive dose slows the vital functions until they cease.

For most of the 20th century, morphine was tightly controlled. Patients rarely got doses outside of hospitals, and they were only administered to those in excruciating pain, often dying.

Until drugs like MS Contin. Its morphine was enveloped in a special coating. The morphine passed through the coating slowly, the way helium seeps out of a balloon overnight. The Contin in the name referred to the slow, continuous release of morphine. The gradual release prevented the rush to a high as well as the crash. No high, no crash—no addiction, at least in theory.

MS Contin was originally designed for cancer patients. It relieved pain but, thanks to the slow release, the patient didn’t have to be under a doctor’s direct care. The patient could take it as part of end-of-life hospice. They didn’t have to die in an austere hospital. They could be at home, among what was familiar and cherished.

MS Contin entered the U.S. market in 1984. It truly met its moment.

The medical community was in the middle of a 20-plus-year examination of the idea of pain. Traditionally, pain was a symptom. You went to the doctor because something hurt. They treated what caused the hurt. The hurt went away.

Sometimes, though, the hurt doesn’t go away. Sometimes it is chronic, like most back pain or arthritis. The nerve endings are forever disturbed. Their pain signals never subside.

The medical community began to embrace the idea that drugs should be aggressively addressing all pain problems, acute and chronic.

This new paradigm manifested itself in quite a few ways—through formation of an American Pain Society and the American Pain Foundation; through creation of Departments of Pain Medicine at hospitals; and through the affirmation that pain is a vital sign, just like pulse or blood pressure.

Pharmaceutical companies welcomed and encouraged these efforts, and it’s not hard to see why. According to the National Cancer Institute, about 600,000 Americans a year die of cancer. About 50 million suffer from chronic pain. Moving from a cancer drug to a drug for chronic pain represented an 80-fold increase in the market for a product like MS Contin.

MS Contin became a financial winner. Sales hit $170 million a year, “dwarfing anything that Purdue Frederick had sold in the past,” wrote Patrick Radden Keefe in Empire of Pain, his chronicle of the opioid crisis and the role played by Purdue and the family that owned it. They formed a subsidiary, Purdue Pharma, to take over MS Contin and the prescription drug business, leaving Purdue Frederick to tend to Senokot and other over-the-counter remedies.

Unfortunately for the newly minted pharma company, MS Contin’s patent was nearing an end. When drug patents expire, generics invade the marketplace, and sales on the original plummet. Anticipating that end, Purdue developed a new formulation. In place of morphine, Purdue scientists wrapped the Contin coating around oxycodone, another opioid, but one that’s 50% more powerful. New drug, new patent, new patent protection.

Welcome to the stage, OxyContin. The year is 1996.

OxyContin was a spectacular success: $1 billion in sales in the first four years. Purdue rolled out a range of doses: 10 milligrams, 20, 40, 80, and for a time, 160.

But there was a problem. A little math will demonstrate.

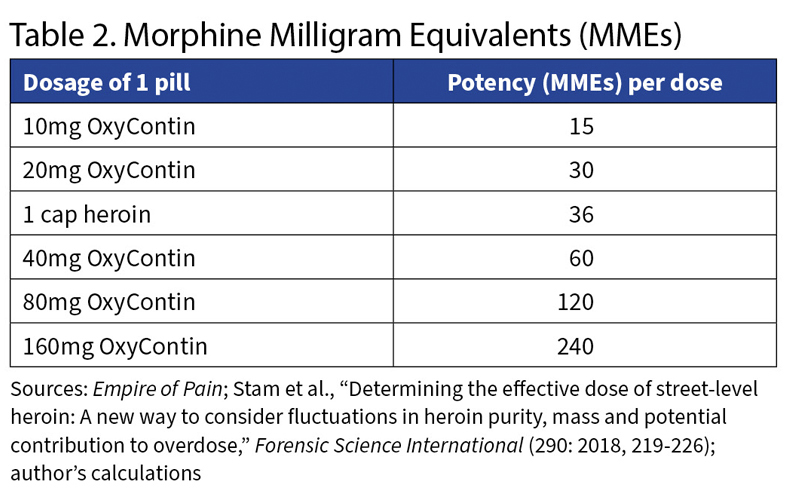

First: Opioids are measured by how powerful they are compared with morphine, in units called morphine milligram equivalents, or MMEs.

Morphine is 1 MME. Heroin is three times as potent as morphine, so it is 3 MMEs. So taking 1 milligram of heroin would pack the same punch as 3 milligrams of morphine.

How many MMEs does a heroin addict seek? I found one reasonable answer tucked into the July 2018 issue of Forensic Science International, a peer-reviewed journal that publishes scholarly work on the intersection of police work and science. Australian researchers analyzed 983 caps of heroin seized in the state of Victoria—a “cap” being the typical size for one hit. When you buy it on the street, heroin is always mixed in with other dilutants—sometimes, dangerously, other depressants; sometimes stimulants as mundane as caffeine. Sometimes the Australians found artificial sweetener. They were trying to see if the amount of powder in the cap told you how powerful the dose would be.

The answer: It tells you a little. More important is how much heroin is mixed into a cap.

The median cap contained 12 milligrams of heroin. There was a lot of variation; the interquartile range (the gap from 25th percentile to 75th) was 6.6 milligrams, meaning the typical street chemist is no Walter White. Still, a good guess for the potency of a typical cap of heroin is 36 MME.

Now look at Table 2. It directly compares the potency of OxyContin’s various doses with a typical cap of heroin. Wrapped in that Contin coating was a luscious high. The addict’s challenge: getting around the coating.

Before long, they knew how.

By 1997, less than two years after OxyContin’s launch, Purdue’s sales force was hearing tales of people crushing an Oxy, then snorting it, cooking it, or shooting it into their veins.

A high-school cheerleader told journalist Barry Meier she would crush a pill with a tube of ChapStick. Or a friend would suck on a pill, spit it out, wipe it on his T-shirt and wrap it into the crease of a dollar bill. Then he put the bill in his mouth and bit hard. He poured the contents onto a compact disc case, and together they snorted it up.

By 2000, the opioid crisis was burgeoning. Meier’s book Pain Killer paints the picture along the main drag of Pennington Gap, a town of 1,781 tucked into the western corner of Virginia between Tennessee and Kentucky. Dealers perched along the main drag, holding up two fingers if they had 20-milligram Oxys (equivalent to a cap of heroin) and four fingers if they had 40s (equivalent to two).

That year 3,785 people died of prescription opioid overdoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 10% more than the year before.

The early epidemic was centered in Appalachia, but abuse was creeping into the Midwest and the West Coast states, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. In Maine, a federal prosecutor sent letters to thousands of doctors warning them about the dangers of abuse and “diversion” of OxyContin.

Diversion meant getting a prescription, then selling the pills. Patients would doctor-shop and pile up prescriptions, either to feed their own dependence or to sell.

If you were on Medicaid, a bottle of pills cost $1. On the street, 20-milligram Oxys sold for $20 apiece, and 40-milligram pills sold for $40 each.

Less scrupulous physicians—so-called pill mills—would churn out prescriptions all day, their offices stuffed with addicts, their parking lots a kaleidoscope of out-of-state plates.

Workers’ compensation insurance was quickly dragged into the mix. People with legitimate injuries would receive prescriptions, and some became addicts. And some addicts feigned their way into the system, or malingered to stay in. And some doctors abused the system. From 1996 to 2000, for example, total prescription drug payments doubled in the California workers’ compensation system.

The problem didn’t grow in a vacuum. A House of Representatives subcommittee held a hearing in Bucks County in 2001 to focus on doctors who overprescribed. Federal prosecutors were warning doctors about abusive practices. Eventually they secured guilty pleas from three Purdue executives for “misbranding [of the] addictive and highly abusable drug OxyContin.” The executives and the company paid fines exceeding $600 million. Purdue paid another $75 million to resolve a class action of similar theme.

But the problem kept growing. Check Table 1—7,461 deaths in 2003, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. That was the year conservative firebrand Rush Limbaugh got hooked.

Actor Heath Ledger died from an overdose in 2008. He was one of 13,149. Crushed Oxys, harking back to the crisis’ Appalachian roots, became known as “hillbilly heroin.” Unscrupulous physicians had perfected the pill mill. Florida had 900, and about one-fourth of all the nation’s oxycodone prescriptions were shipped to that state. In 2010, 98 of the 100 biggest prescribers of oxycodone were Florida doctors. From that state, Interstate 75 became the “Oxy Express,” an opioid pipeline satisfying demand in Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, and other states.

California workers’ comp insurers spent almost $1 billion on opioid prescriptions that year—almost one-third of their total spending on pharmaceuticals. Researchers were finding that “in many cases opioids were being prescribed for reasons that could not be justified clinically,” said Alex Swedlow, president of the Oakland-based California Workers’ Compensation Institute (CWCI).

Doctors, regulators, lawmakers, and insurers all saw what was happening, and solutions came from every direction. Some applied to across the medical spectrum.

Many states began to require that doctors check with a database of prescriptions written in the state.

Pharmacies report to the database the prescriptions they have written. In Indiana, for example, they submit reports weekly. A check of the database would reveal if an addict was doctor-hopping.

Each state names its own database, usually a somewhat strained acronym. California’s database, for example, is CURES—Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System. Collectively the databases are known as prescription drug monitoring programs and are often referred to by the abbreviation PDMP.

PDMPs have been around for some time—decades, according to Bogdan Savych, a public policy analyst at the Workers’ Compensation Research Institute,[1] a not-for-profit organization based in Cambridge, Mass. The earliest, back in the 1930s, were on paper and came out maybe monthly. Doctors were not required to check them. So they rarely did.

This century, reporting turned electronic as pharmacies and doctors’ offices computerized. And with the opioid epidemic, several states started to require that doctors check the PDMP before prescribing. It was these “must-access” PDMPs that Savych and fellow analyst David Neumark studied.

WCRI collects workers’ comp data from 33 states. Eighteen of them had implemented must-access PDMPs during the opioid epidemic. In every one of them, opioid prescribing had declined.

But opioid prescribing was falling everywhere, even the 15 states WCRI tracks that lack PDMPs.

It seemed like everyone was trying to solve the problem. Florida, for example, curtailed the pill mill industry beginning, after fits and spurts, in 2011.

The CDC published guidelines on prescribing opioids in 2016. The guidelines became a template for state laws to restrain abuse. They advised:

When to start or continue an opioid prescription (“only if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh the risks”).

What to prescribe (“the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids. … Three days or less will often be sufficient.”).

How to assess the risk and minimize it (“review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions”).

The researchers’ challenge: how to determine whether must-have PDMPs helped, and to measure their contribution.

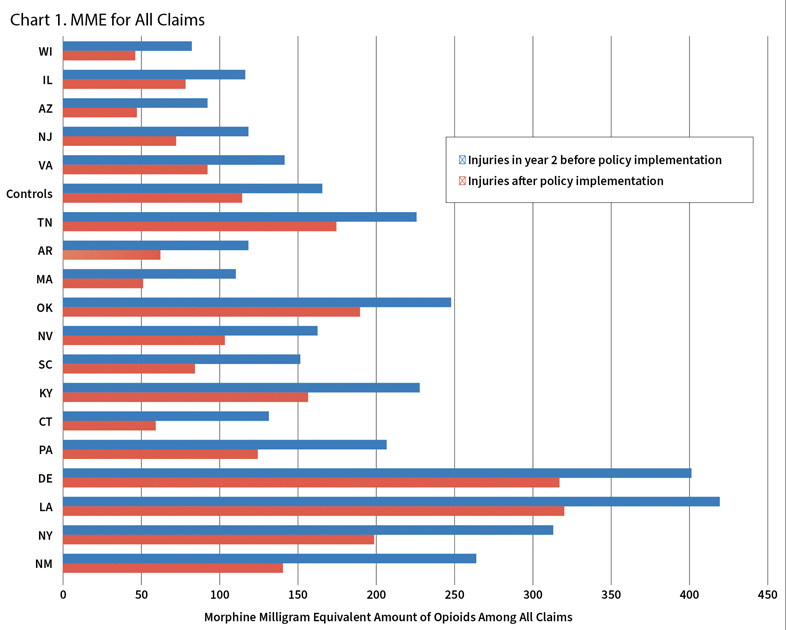

They began by bundling together the 15 non-PDMP states into a single control group. Then they compared each of the PDMP states with the control group of states. If the vast majority of PDMP states showed bigger decreases than the control states, one could conclude that PDMPs were effective. And they generally were, as Chart 1 illustrates. Here the researchers compare the total amount of opioids prescribed, in morphine milligram equivalents. This shows that 13 of 18 states with PDMPs outperformed the control states.

This visual analysis is very effective, Savych said, but can get murky if overused.

“You can do it with two states, or three states, or four states,” he said, “but what about 30 states?

To analyze more precisely, WCRI developed a regression model, controlling for several variables that might differ from state to state: industry composition, unemployment, household income, the percentage of people disabled, and the percentage without health insurance.

The researchers also had to line up the years carefully. The states that mandated use of PDMPs didn’t do so at the same time, so WCRI had to create a Time Zero, a moment by which to synchronize events that actually happened over several years. The researchers based it upon the date the must-access PDMPs took effect.

They found that workers were just as likely to receive opioids as in the past, but prescriptions, on average, were less powerful. And workers received fewer prescriptions, on average.

And WCRI quantified it. The amount of opioids prescribed fell 12%, and the likelihood that a worker on opioids received them over the long term also fell by 12%.

Other solutions were unique to workers’ compensation, and they often applied to all prescriptions, not just opioids. In a 2020 systematic review, the D.C.-based consulting firm Mathematica listed more than a dozen different types of responses within the workers’ comp world.

A common one: Texas and about a dozen other states have developed guidebooks for prescribing drugs known as formularies. The formulary lists a drug and the circumstances when the insurer will pay for it. If it is used for a different purpose or if it isn’t in the formulary, the insurer has to OK its use in advance.

Your health insurer probably has its own formulary, too. You hear about it if you get a notice that a drug you’ve been prescribed is not covered by the plan. That formulary is drawn according to state laws, but individual insurers can tailor their own list. The workers’ comp formulary is uniform from carrier to carrier.

Texas implemented its formulary in 2011. In one year, the number of injured workers who received drugs that the formulary discouraged fell by 67%.

California was typical of most states adopting formularies. It tried to tie its composition to objective, clinical standards. It also included provisions for appeal—to a utilization review board and to a final independent medical review. The appeals minimized the chance that workers could be bereft of drugs that they needed.

The state also began tracking doctors more diligently. Not all doctors overprescribed. A handful were responsible for the vast majority of prescriptions. “The problem was coming from a small circle of providers,” Swedlow said. “The vast majority of physicians were doing the right thing to begin with.”

These and other changes made a dramatic difference. For the past decade, workers’ comp’s prescription drug costs have fallen an average of 2.6% annually, said Raji Chadarevian, director, medical regulation and informatics at the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI).

“What, you may ask, is causing this shift?” he offered at the NCCI’s Annual Issues Symposium this year. “And the answer in one word is: opioids.”

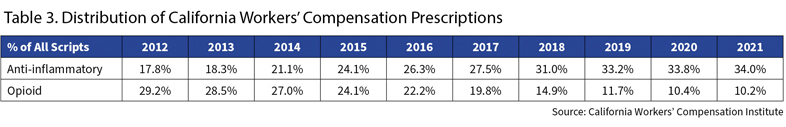

Table 3 shows that opioids went from almost 30% of prescriptions in California in 2012 to 10% last year. Taking their place were NSAIDs, a tamer class of drugs like Tylenol or Celebrex. They have almost doubled their share, to 34% of all prescriptions.

Addressing the crisis also improved worker outcomes. Both WCRI and CWCI found that opioid prescriptions actually lengthened the amount of time it took for a worker to return to their job. WCRI found that opioid prescriptions made it take three times longer to return to work. CWCI found that claims without opioid use had 25% fewer days of disability.

Drugs aren’t the only way to take away pain, as Chadarevian noted in a 2020 address. Injured workers with chronic pain averaged 23 visits during their first year with an injury in 2018, 15% more than six years earlier. Use of orthotics—custom shoes or harnesses—had grown 26%.

Other treatments are less common but slowly gaining traction.

Just under 1% of chronic pain patients get massage therapy, but that’s more than double six years earlier. About one patient in 40 received mental health services for their pain, a 20% increase.

“This is a promising shift,” Chadarevian said. “The pain does not magically disappear. Its persistence remains an important factor in the injured worker’s path to recovery and return to work.”

What has made the difference? Swedlow initially demurs: “I’m not sure it’s possible to create a pie chart of responsibility.” He does mention guidelines to control the cost of drugs, including encouraging the use of generics. And he points to the formulary and the process of reviewing and appealing decisions. Public awareness matters as well, he said.

Mathematica’s systematic review noticed that it works better to reach out to many stakeholders—prescribers, pharmacists, insurers, and patients—instead of just one. Using technology to track and manage prescriptions “has clear advantages,” it noted. And programs that taught stakeholders, then reinforced that training, were likely to be successful.

In workers’ comp, the effort against prescription opioids was an insurance success. Opioid use has fallen, as have payments. Workers apparently are recovering at the same pace, if not quicker.

Opioids continue to be a major problem, but it’s not from prescriptions. Glance back at Table 1. The number of deaths tied to prescription drugs has flattened.

The human toll, unfortunately, continues to rise. First heroin deaths rose. Now deaths related to fentanyl are driving the increase. Fentanyl is 30 times stronger than heroin. Doses aren’t measured in milligrams. They are measured in micrograms per hour.

It typically enters the body, not via a pill, but through a patch.

Few fentanyl deaths come from the prescription variety. California’s comp insurers spent about $400,000 on fentanyl prescriptions last year. It’s illegal fentanyl that kills today.

Fentanyl’s toll comes from two sources—the traditional abuse of the drug itself and the use of fentanyl in combination with other drugs, said Sara E. Hines, an associate policy researcher at the Rand Corporation.

“We’re also seeing big increases in deaths involving stimulants like cocaine,” she wrote in an email, “even though stimulant use has been pretty flat over time. That increase has been almost entirely due to contamination of stimulants with fentanyl. … Many stimulant users haven’t used opioids and don’t have any tolerance to the drug, making it much easier to overdose.

“That doesn’t mean that I think we should go back the old days of overprescribing opioids (e.g., giving someone a two week prescription of opioids for wisdom teeth removal when most people will only need to take them for a couple days), but I do think we need to be careful not to go too far in the other direction and make sure that we are not abruptly cutting off patients who have been using opioids for a long time or under-treating severe pain that often accompanies workplace injuries.”

As the number of deaths compounds, it is tempting to use the cliche, “The operation was a success, but the patient died.”

But there have been successes, and not just in getting control of their costs. We’ve refined when to prescribe opioids. Patients know they can be dangerous. You have to give credit for all the effort, for the successes achieved, and for the quest to find better ways to manage pain.

JIM LYNCH, MAAA, FCAS, is a freelance writer.

Legal or Illicit, the Anguish of Withdrawal Is Real

Quitting is brutal.

Author Beth Macy called her book Dopesick after the street term for withdrawal. As one user told her: “You’re throwing up. You have diarrhea. You ache so bad and you’re so irritable that you can’t stand to be touched. Your legs shake so bad you can’t sleep. You’re as ill as one hornet could ever be.” Often users were drawn back to a drug to avoid dopesickness as much as to enjoy the high.

If the user loses their prescription, their desperation sends them scampering for any they can find—legal or not.

The medical community knows this from hard experience. In 2010, Purdue Pharma developed a tamper-resistant coating for OxyContin. If you soaked a pill or tried to lick off the coating, the pill turned to mush. If you crushed it, you were left with a gummy paste. The days of the easy high were gone.

The heroin epidemic went into overdrive.

Take a look at Table 1. Prescription drug deaths flatten through 2016. Heroin deaths nearly quintuple.

Did the reformulation cause the heroin problem?

In a 2018 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research argued just that. Economics professors William N. Evans, Ethan Lieber, and Patrick Power studied the matter and concluded, “The rapid rise in the heroin death rate since 2010 is largely due to the formulation of OxyContin.”

They reached this conclusion via a statistical analysis first suggested in 1960 by a Princeton University professor with a name that would charm any data geek: Richard E. Quandt.†

To do so, the economists first fit a quadratic spline to the rate of oxycodone prescribed.† † To find the exact break point, they tested every month between 2010 and 2012 with a statistical F test. They set the break point where the F test was highest: August 2010.

They followed the same steps looking at the rate of heroin poisonings. Those began to accelerate in September 2010—one month after reformulation.

The authors concluded: “The reformulation did not generate a reduction in combined heroin and opioid mortality—each prevented opioid death was replaced with a heroin death.”

The FDA didn’t go that far, but in a 2020 review, it concluded that any decrease in mortality that the reformulated OxyContin brought was “offset, or more than offset, by increases in illicit opioid overdose due to substitution.” It stopped short, though, of saying the reformulation caused the shift.

To some—like Sara E. Heins, an associate policy researcher at the Rand Corporation—prescription opioids continue to seed the epidemic.

“There are surveys that show a large percentage of people who use opioids first used prescription opioids,” she said. “In qualitative research, opioid users often describe the experience of receiving prescription opioids and then turning to diverted opioids … or to things like heroin when they’re no longer able to get prescription opioids.”

“Opioids still hold an important place in pain management,” Hines said. “There’s still a concern that if you aren’t offering adequate pain management, patients will suffer and might turn to other means of controlling their pain which could include diverted opioids. To get patients safely off opioids requires as much thought as how to prescribe them. Maybe more.”

In any case, the cold-turkey solution doesn’t work. The CDC acknowledges as much as it revises its guidelines.

It has criticized its own 2016 guidelines because they could be misinterpreted as rigid standards. Sometimes doctors didn’t want to prescribe for them, some pharmacies didn’t want to fill their script, and some insurers would refuse to pay.

The shunning shamed patients, they told the CDC. Patients felt like failures, unable to grapple with pain when denied pills deemed too dangerous to take. Many considered suicide.

The CDC now notes that “the discontinuation of long-term, high dose opioid therapy, especially over a short period of time, is associated with adverse events, including overdose mortality.”

“Clinicians have a responsibility not to abandon patients,” according to the CDC, so it recommends avoiding “rigid standards related to dose or duration of opioid therapy.”

—JL

Notes

† He is better known as a number-cruncher behind the “Judgment of Paris,” a 1976 taste-off that demonstrated that California wines are just as good as the French. That provided a crucial boost in making the California wine industry the success it has become. In the 2012 “Judgment of Princeton,” his work reached a similar conclusion, except this time with New Jersey wines. Sales and prestige there have yet to follow the California arc.

† † They used data from MarketScan, a set of databases maintained by IBM. Researchers used a database with information on inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug use on more than 37 million persons across 350 self-insured plans.