By Carlos Fuentes

“The Strategic Role of Ownership Structure for Insurance Companies” published in the March/April 2022 issue of Contingencies states that sometimes, for a variety of reasons, mutual insurance companies (“mutuals”) convert to stock insurance companies (“stocks”). This article illustrates the strategic considerations that surround demutualizations using Scottish Widows, a provider of life and pension products, as a case study under the premises that were applicable at the time of the transaction.

In order to be acquired by Lloyds TSB, a bank with a portfolio of personal investment products, Scottish Widows demutualized to take advantage of economies of scale, economies of scope, and complementarities between the actuarial and investment functions. Lloyds TSB expected to improve its portfolio management by combining actuarial and banking talent. It was clear to the participants that without economies of scale, no firm can compete globally.

The Players

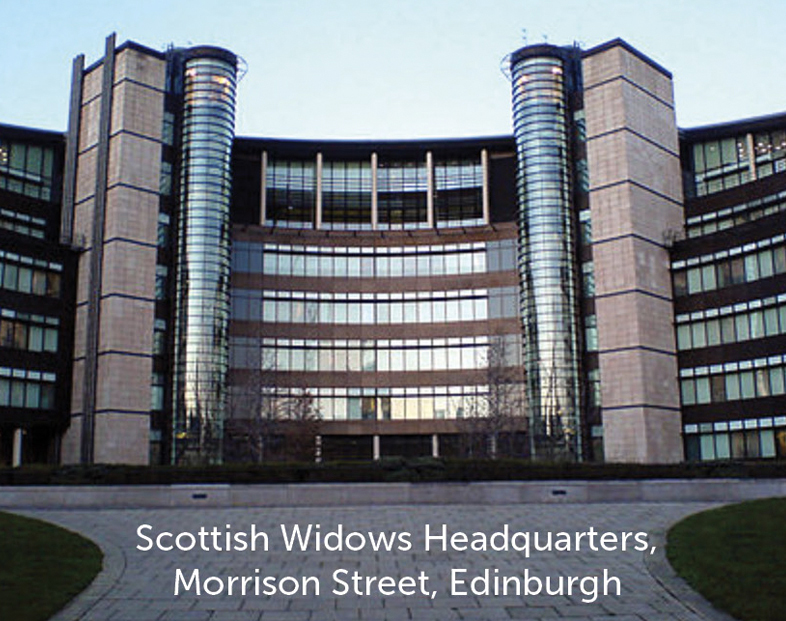

Scottish Widows

Scottish Widows is an investment company headquartered in Edinburgh, Scotland, now a subsidiary of the Lloyds TSB Group. The Scottish Widows Fund and Life Assurance Society opened in 1815 as Scotland’s first mutual life office with the purpose of providing for widows, sisters, and other female relatives of fund holders. One of the most recognizable brand icons in Britain,[1] the Scottish Widow first appeared in a television advert directed by David Bailey in 1986. There have been four “widows” to date: Deborah Moore (daughter of Roger Moore) from 1986 to 1994; Amanda Lamb from 1994 to 2005, Hayley Hunt from 2005 to 2014, and Amber Martínez from 2014 to the present.

Lloyds TSB

Founded in 1765, Lloyds Bank is one of the oldest banks in the U.K. and by 1995 had become one of the largest after a series of domestic and international acquisitions, including Lloyds Abbey Life. The Trustee Savings Bank (TSB) was formed by Henry Duncan in Scotland in 1810 with the intention of helping poor parishioners save money for times of hardship. The success of the scheme led to the establishment of similar banks throughout the country and eventually to the creation of The Trustee Savings Bank Association. Eventually, the various banks consolidated into TSB England and Wales, TSB Scotland, TSB Northern Ireland, and TSB Channel Islands. Years later, the Trustee Savings Bank Act of 1985 allowed the merger of the Scottish and Channel Islands operations into TSB England and Wales under the name TSB Bank plc. The new bank was floated on the London Stock Exchange, and TSB Northern Ireland was sold to Allied Irish Banks where it was re-branded as First Trust Bank.

Lloyds TSB Group plc, a bank based in the United Kingdom, was created in 1995 following the merger of the TSB Group and the Lloyds Bank Group. The head office is in London, but Lloyds TSB operates globally. The group contains companies that provide banking services for individuals and businesses, mortgages, investment and, after the acquisition of Scottish Widows, life assurance. Lloyds TSB Group ranked fifth in the U.K. and has the largest share of personal and business banking in the U.K.

After the 2008 rescue of Halifax and Bank of Scotland (HBOS),[2] Lloyds TSB was renamed Lloyd Banking Group. In 2009, following the liquidity crisis, the U.K. government took a 43.4% stake in Lloyds Banking Group. On April 2013, a number of Lloyds TSB branches in England, Scotland, and Wales were combined with branches of Cheltenham & Gloucester to form a new bank operating under the TSB brand and divested by the group. The new bank began operating on September 2013 as a separate division within Lloyds Banking Group. TSB was floated on the London Stock Exchange on June 2014 and was acquired by Banco Sabadell one year later, and subsequently delisted. The remaining business of Lloyds TSB returned to the Lloyds Bank name in September 2013.

Demutualization and Acquisition

Scottish Widows’ proposed demutualization and acquisition by Lloyds TSB was overwhelmingly approved by members of Scottish Widows at a special general meeting held on December 1999, approved by the U.K. courts in February 2000, and became effective in March 2000. Under the terms of the transaction, Scottish Widows became a full subsidiary of Lloyds TSB in exchange for a cash payment of 5.7 billion pounds sterling to policyholders based on the following business valuation:

- Estate (assets in excess of those required to meet policyholders’ reasonable expectations): 2.8 billion pounds.

- Business in force: 1.1 billion pounds.

- Infrastructure, operations, and brand name: 1.8 billion pounds.

Every policyholder received a fixed allocation of five hundred pounds to compensate for the loss of voting rights, for an estimated cost of 0.8 billion pounds. In addition, qualifying members that held participating policies were entitled to a variable allocation to compensate for the loss of rights to surplus on dissolution of Scottish Widows, costing 4.9 billion pounds. The average windfall (including the fixed amount) to participating policyholders was 5,600 pounds; some received up to 25,000 pounds.

Strategic Considerations of the Acquisition

Each of the four biggest U.K. banks had tried to sell its own brand of life insurance and pension products with little success because banks were perceived as providers of low-value offerings. According to Lloyds TSB, for example, only 4% of its customers were willing to purchase life or pension schemes from a bank. The best solution, judged by the actions of industry participants, was to expand horizontally through the acquisition of insurance companies. The logic was to enlarge scale and scope in light of the government’s pressure to lower the costs of financial products, which by 2000 were already at historical lows as the result of fierce competition. With an annual fee limit of 1% of the product’s value, economies of scale are required to spread fixed costs, and economies of scope to cross-sell. Furthermore, persistently low bond yields forced customers to pay attention to the eroding effects of commissions and fees and encouraged them to shift their investments from fixed-income instruments to equities. Finally, banks realized that life insurance and pension were among the few financial products that were expected to grow substantially. The acquisition of Scottish Widows by Lloyds TSB must be understood in this context.

Economies of Scale[3]

Economies of scale were expected to save 60 million pounds—the result of a new cost structure[4] and an improved distribution system that combined the largest bank network in the U.K. with a broad agent infrastructure. A wide distribution[5] and service network was expected to facilitate customer transactions and signaled that Lloyds TSB was the company committed to providing personal financial products backed by a large pool of assets. Finally, with the European integration, economies of scale were to be part of the admission ticket for global competition.

Economies of Scope[6]

The new firm was expected to offer a wide array of investment and pension products, but also the “independent” financial advice that was part of Scottish Widows. Customers would enjoy the convenience of “one-stop shop” while providing—perhaps unknowingly—marketing information that the bank intended to employ to create its next generation of products and services. Additionally, it was reasoned that an ample portfolio of insurance and investment products would open the possibility for bundling, which has three important benefits: increased sales, lower lapse rates,[7] and product cross-subsidies.

Horizontal Differentiation[8]

Participating life and pension products are not easily comparable due to the long-term nature and uncertainty of their cash flows. Thus, customers—even sophisticated shoppers—cannot ascertain whether a high-cost life and/or pension product provides high or low value. Under these circumstances, the intangible value of a popular icon such as the Scottish Widow[9] becomes a great asset to Lloyds TSB by horizontally differentiating its insurance products and creating an umbrella branding effect on its banking services.

Complementarities[10]

Sophisticated asset/liability management in the banking and life/pension arena is a factor for success in the current environment of low interest rates, razor-thin commissions, and intense competition. Lloyds TSB expects to unlock the elusive synergies of actuarial and banking expertise to improve risk management and investing functions. The expectation was to create value for customers (not to redistribute it), which would translate into higher profits. Ultimately, the acquisition of Scottish Widows increased the importance of strategic management as new products mingled elements of investment with elements of financial security.

The Record of Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A)

He who wonders how much value is created with M&A should be forgiven if his guess is along the lines of “a substantial amount.” After all, many smart people are involved in M&A and enormous amounts of money are spent to ensure that the transaction is a success. The fact of the matter, however, is that most mergers and acquisitions fail to create value—and many of them destroy it.[11] Here’s why:

- The Agency Problem—As discussed in “The Strategic Role of Ownership Structure for Insurance Companies,” managers and the people they employ during an M&A profit from the transaction. Who among us would decline the opportunity to become rich even if doing so is at the expense of owners (e.g., shareholders) who have no knowledge of the history of M&As and who cannot assess the financial implications of the operation?

- The Buyer Tends to Overpay—Once the motivation to merge or acquire exists, the buyer will make an extra effort to complete the transaction. If the company to be acquired is private, the buyer has to deal with the problem of asymmetric information.[12] If the firm is public, shareholders will not approve the sale unless they are rewarded with compensation that exceeds stock prices because shareholders can easily sell their stock in the market.[13]

- Management’s Overconfidence—Managers are generally overconfident about their abilities. In addition to this, and perhaps surprisingly to those who have not followed M&As closely, it frequently happens that management does not really understand how the new entity can create value but instead relies on, and repeats, mantras like “our talented team will have the opportunity to develop revolutionary products at low costs that will delight customers”—whatever that means.[14]

- Execution—The fact of the matter is that although everybody understands that “ideas don’t make you rich, the correct execution of ideas does” (Felix Dennis), most companies struggle with execution. The historical record is unambiguous in this respect.[15]

Final Remarks

The branding campaign of Scottish Widows is a textbook example of how perceptions influence customer decisions and how marketing can create value for a company—not necessarily for the customer.

The acquisition of Scottish Widows by Lloyds TSB reflects the current view that horizontal differentiation, economies of scale, economies of scope, and complementarities are the strategies to follow for global competition in the financial sector. Yet, one should not lose sight of the fact that aspirations—whether genuine or deceitful—frequently differ from reality.

Carlos Fuentes, MAAA, FSA, FCA, MBA, MS, is president of Axiom Actuarial Consulting and managing partner of Your2tor.

The opinions expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author. They do not express the official views of the American Academy of Actuaries, nor do they necessarily reflect the opinions of the Academy’s officers, members, or staff.

References

[1] See https://www.youtube.com/user/scottishwidows and [2] HBOS plc was a wholly owned subsidiary of the Lloyds Banking Group and the holding company of Bank of Scotland plc. [3] Economies of scale are cost advantages reaped by companies when production is increased and costs are reduced. [4] Lloyds TSB expected minimum layoffs. [5] Combining insurance and bank products requires training of salespeople which may be expensive and not without glitches. [6] Economies of scope refers to the reduction of per-unit costs through the production of a wider variety of goods or services. [7] Many actuarial studies confirm the commonly held belief that product bundling increases horizontal differentiation and makes rate comparison more difficult, all of which results in lower lapse rates. [8] Horizontal differentiation refers to differences between products that increase perceived benefit for some consumers but decrease it for others. For example, the same automobile can be offered with automatic or manual transmission. Vertical differentiation refers to features of a product that makes it better than the products of competition. For example, the higher resolution of a monitor, the more desirable it is. [9] The results of the branding campaign undertaken in 1986 exceeded expectations: brand recognition shot up from the historical average of 30% to 86% in six weeks and has remained high since then. No other insurance company in the U.K. has ever produced such a well-received icon as the “Widow.” I can attest to the success of the branding campaign. I remember the widow wearing a cape in pictures that advertised the company in the London subway. Years later, I am authoring an article about Scottish Widows. [10] A complementary service is a service whose use is related to the use of an associated service. Two services (A and B) are complementary if using more of service A requires using more of service B. [11] See “Navigating the Risks of the Contemporary M&A Market: Results of a 2016 Crowe Horwath LLP and FERF Survey,” Financial Executives International, December 2016. [12] Asymmetric information refers to the condition under which one party is more informed than the other in a transaction. The more informed party frequently can profit from such knowledge as in the sale of a used car. [13] See “Overpaying, Unclear Goals Biggest M&A Risks Today,” Dave Pelland, Financial Executives International, December 2016. [14] See “The Overconfidence Trap,” Deloitte Insights, August 2007. [15] In “Why DaimlerChrysler Never Got into Gear,” Harvard Business Review, May 2007, author Michael Watkins states that: “Economists have estimated that between 1997 and 2001, large acquisitions cost the shareholders of acquiring firms $397 billion.”