By Bradley J. Piper and Mary L. Gabe

Why maintaining a zero-dollar MA-PD premium plan is worth the effort

Medicare Advantage-Prescription Drug (MA-PD) plans with a zero-dollar ($0) member premium are incredibly popular among Medicare beneficiaries. In fact, February 2019 enrollment data indicates about 55% of individuals who enrolled in an MA-PD plan elected a zero-dollar premium plan.[1]

Many Medicare beneficiaries, especially healthier individuals with limited expected medical costs, are attracted to zero-dollar premium plans that require no monthly financial commitment. In return, the beneficiaries are willing to accept the higher member cost-sharing (i.e., deductibles, copays, and coinsurance) that generally accompanies these plans. Because these plans offer benefits richer than traditional Medicare and include Part D pharmacy coverage for no premium, zero-dollar premium plans routinely perform well during the annual enrollment period (AEP) as it relates to member retention and growth. However, what happens to membership when the organization adds a premium to the zero-dollar premium plan?

In the MA-PD market, beneficiaries are generally “sticky” in their purchasing practices—that is, they typically would prefer to avoid changing their coverage from one year to the next. They often do not want to change doctors or specialists, nor do they want to change pharmacies or identify which specific prescriptions a different plan may or may not cover. Many Medicare beneficiaries value the benefits and level of customer service they receive from their existing health plans and may not want to switch plans or carriers. Is this stickiness strong enough to overcome the loss of zero-dollar premium health care, especially in geographic regions where another carrier continues to offer a zero-dollar premium option?

Plans that add a member premium to their prior zero-dollar premium plan can expect to lose membership if other zero-dollar plan options exist in the county.

We reviewed public enrollment data released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for individual MA-PD plans from 2016 to 2019. We excluded Medicare Advantage-only plans without Part D coverage, special needs plans (SNPs), employer group waiver plans (EGWPs), Medicare Cost plans, Medicare-Medicaid plans (MMPs), and medical savings account (MSA) plans as well as all plans in Puerto Rico. We summarized the membership and premium for each plan from 2016 to 2019 and identified the membership change associated with member premium changes.

The membership losses discussed in this article generally occur only when the beneficiary has another zero-dollar premium plan option in that person’s county of residence. In cases where the last zero-dollar premium plan adds a premium, historical data suggests there is often no corresponding membership loss for the plan, possibly because no other zero-dollar option exists. Because such cases are infrequent, and because such cases typically do not result in a membership loss, we exclude them from the remainder of our analysis. The remainder of this article focuses on situations where a plan adds a premium to its zero-dollar MA-PD plan, but an alternate zero-dollar MA-PD plan exists in the county for members to choose.

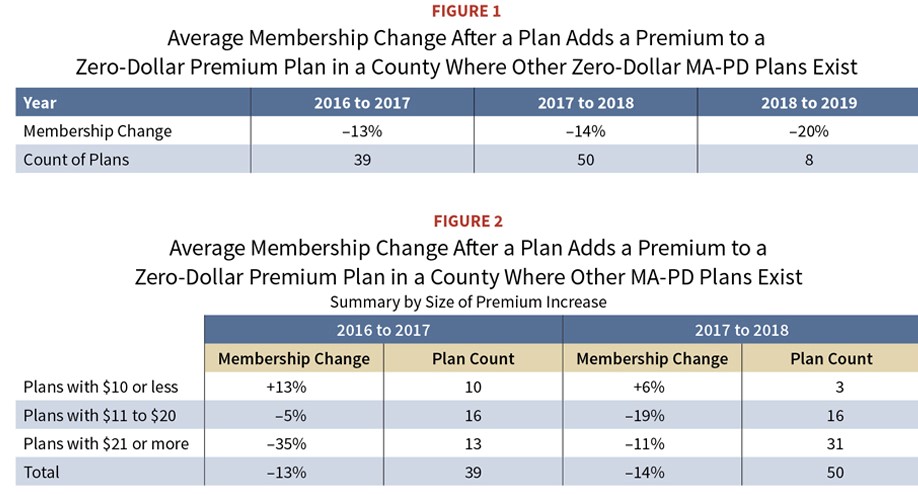

Plans that change from a zero-dollar premium plan to a non-zero-dollar premium plan experience a significant loss of membership when at least one other zero-dollar premium plan exists in the county. See the table in Figure 1 for a summary of the average membership loss for each year. As a comparison benchmark, the MA-PD market as a whole (with the same exclusions listed in footnote [1]) grew 6% to 8% per year during this period.

As Figure 1 shows, an MA plan that added a premium to a 2016 zero-dollar premium plan lost an average of 13% of its membership in 2017 on a net basis. This membership decline intensified in more recent years, as the membership loss was 14% and 20% for 2018 and 2019, respectively. Given the overall growth in the MA-PD market of 6% to 8% per year during this timeframe, these plans not only realized membership losses of 13% to 20%, but they also failed to capture the growth experienced by the market.

As a general strategy, plans try to avoid adding a premium to a zero-dollar premium plan. As a result, there are a limited number of plans underlying the Figure 1 results. Specifically:

- Thirty-nine unique plans added a premium in 2017 to a zero-dollar premium plan in 2016. Those 39 plans had roughly 160,000 members in 2016.

- Fifty unique plans added a premium in 2018 to a zero-dollar premium plan in 2017. Those 50 plans had roughly 250,000 members in 2017.

- Eight unique plans added a premium in 2019 to a zero-dollar premium plan in 2018. Those eight plans had roughly 20,000 members in 2018.

Because there were so few organizations that added a premium to their zero-dollar premium plans in 2019, we recognize the 2019 result of an average loss of 20% of membership may be an outlier. However, the Figure 1 results generally tell the same story—membership declines when a plan adds a member premium to a zero-dollar premium plan and there exists another zero-premium plan in the county. Although we cannot draw any of the following conclusions from our analysis, we believe the number of plans adding a premium can vary from year to year depending on a number of external factors, such as CMS payment rate changes, plan experience, provider contracting, population risk scores, and many others.

Plans considering the addition of a premium to their zero-dollar premium products will wish to exercise caution, as some membership decline is likely to occur. Further, it is often the healthiest members who leave the plan for an alternative plan offering a zero-dollar premium. As a result, the original plan may be left with less healthy (i.e., higher-cost) members, possibly resulting in the need for another premium increase the following year. This can create a “spiral” situation where the plan continues to increase premiums year over year to cover costs, and costs (on a per-member basis) climb quickly as the healthier lives leave the plan for other lower-premium options. Such a situation ultimately results in a plan with high, and possibly unmarketable, premiums relative to the benefits offered and low membership—a very undesirable position.

Membership losses are correlated with the size of the premium increase

We further stratified the Figure 1 results to understand how the premium level affects the membership change. Of the plans that added a premium to a zero-dollar premium plan, we created three groups based on the resulting premium:

- Premium of $10 or less

- Premium of $11 to $20

- Premium of $21 or more

The table in Figure 2 shows the membership change for each of these groups. The 2018-to-2019 time period is not included in Figure 2 due to the limited number of plans adding a premium.

The results in Figure 2 show that adding a higher premium generally results in a greater membership loss. In fact, Figure 2 suggests members may actually be willing to tolerate a small premium increase, as both years saw membership growth for plans that increased the premium by $10 or less. We note that relatively few plans went from a zero-dollar premium to a $10 (or less) premium and thus, the small sample size may partially affect the 13% and 6% membership gains in Figure 2.

Many new zero-dollar premium plans entered the MA market in recent years

In the past three years, many new zero-dollar premium MA-PD plans entered the market. In 2017, 156 new zero-dollar premium plans entered the market, followed by significant increases of 313 new zero-dollar premium plans in 2018 and 482 new zero-dollar premium plans in 2019. Although new-entrant zero-dollar premium plans did not capture a large market share over this three-year period (the percentage of total members enrolled in new-entrant zero-dollar premium plans ranged from 2% to 4% during this period), it is a reminder to existing zero-dollar premium plans that new zero-dollar premium plans continue to be introduced. Thus, if an existing zero-dollar premium plan opts to add a premium in a market without other zero-dollar premium plans, there is a reasonable chance a new zero-dollar premium plan may enter the market in a future year with a strategy to attract the members looking to return to a zero-dollar premium plan.

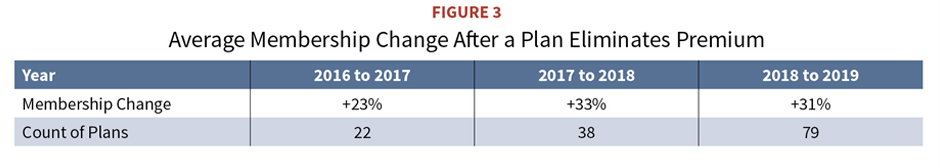

Plans that reduce premiums to zero grow in membership

It is clear from the data analyzed that plans adding premiums to their zero-dollar premium plans generally lose membership. The opposite is also true—plans reducing their premiums to zero generally gain membership. We summarize the membership changes for plans eliminating their premiums in the table in Figure 3.

Membership growth of 20% to 30% is very significant and clearly indicates members are willing to switch plans to enter a zero-dollar premium product.

How to maintain a plan with a zero-dollar premium

The data presented here clearly show a material portion of members may leave a zero-dollar premium plan that adds a premium. For those organizations that choose to offer zero-dollar premium plans, it is important to maintain their zero-dollar premium plans in a financially viable manner. While a full discussion on strategies to achieve and maintain a zero-dollar premium plan is beyond the scope of this article, we include a number of high-level ideas below for organizations to consider:

- Achieve a star rating of at least 4.0 to ensure optimization of CMS benchmark revenue. The MA star rating is part of the MA quality rating program, and organizations that achieve a rating of 4.0 or higher generally receive additional revenue from CMS. This additional revenue relative to a lower star rating may be enough to allow the plan to avoid adding a member premium.

- Invest in risk score coding efforts that improve the accuracy of member risk scores and create appropriate revenue levels. The MA program revenue is risk-adjusted, which means a plan receives more revenue from CMS for enrolled members with more diagnoses or higher-cost diagnoses, and less revenue for enrolled members with fewer diagnoses or lower-cost diagnoses. If not all diagnosis information is accurately submitted to CMS, the risk scores may be incomplete (i.e., lower than the true risk of the enrolled population), resulting in lower revenue payments to the MA plan relative to the expected cost of the enrolled population.

- Focus on utilization management programs. Keeping medical and pharmacy costs down is an important way to avoid premium increases. Utilization management programs focused on reducing inpatient admissions and readmissions, as well as reducing emergency department use are common ways of managing medical utilization and reducing medical expenses. Similarly, programs encouraging providers and members to elect generic drugs over brand drugs will help reduce pharmacy costs.

- Reduce profit margin. It may make sense for plans to reduce profit margins (or even operate at a small loss for one or two years) instead of adding a premium to the zero-dollar premium plan if the organization believes revenue enhancements (such as improved risk scores or improved star ratings) are likely in the next year or two. Such plans will need to ensure compliance with CMS guidance related to submitting plan bids with negative margins.

- Increase cost-sharing. A higher copay will affect only some members—those who need that particular medical service. As a result, copay increases are often “less visible” to members, especially if they do not anticipate needing that particular medical service. However, a premium increase is a very visible change that affects all members and guarantees each member will spend that money out of pocket each month. Therefore, zero-dollar premium plans should consider increasing cost-sharing before the more drastic step of increasing premiums. Similarly, plans should also consider the elimination of a supplemental benefit prior to increasing premium. Any benefit changes must comply with CMS regulations regarding maximum cost-sharing levels as well as total beneficiary cost (TBC) change limits. Premium increases are subject to TBC limits as well.

- Improve provider contracting. Negotiating more favorable provider reimbursement rates could reduce costs to allow the plan to stay at a zero-dollar premium.

- Segment the service area. When segmenting, the plan divides the full service area into smaller service areas called segments. Each segment must have identical Part D benefits, but can have varying Part C benefits, as well as varying premiums. Thus, segmenting could allow the plan to add a premium to a segment in a market with fewer zero-dollar premium competitors, while maintaining the zero-dollar premium in other segments. Adding a premium to only one segment of the plan can also be a good way to understand the tolerance for a premium increase prior to adding a premium to the entire service area. Organizations offering segments must comply with CMS’ specific regulations regarding segmenting.

Conclusion

Although Medicare beneficiaries are “sticky,” this study shows they are also very price-sensitive as it relates to zero-dollar premium plans. Plans will wish to exercise caution when considering the addition of a premium to their zero-dollar premium plans, as those plans tend to lose membership whereas plans reducing their premiums to zero are growing. Thus, an MA organization’s decision to add a premium to a zero-dollar premium plan can be costly in terms of membership loss. In counties where multiple zero-dollar premium plans exist, the addition of a premium to a zero-dollar premium plan can result in a membership loss of 13% to 20%. Organizations should think carefully about the impact of adding premiums to zero-dollar premium plans, and should consider the strategies discussed above before abandoning their zero-dollar premium plan.

Caveats and data sources

Our analysis considered every plan and county in the country, with the following exceptions:

- We excluded all special needs plans (SNPs) from our analysis.

- We considered only individual products and excluded employer group waiver plans (EGWPs).

- We considered health maintenance organization (HMO), HMOs with a Point of Service option (HMO-POS), local preferred provider organization (LPPO), private fee-for-service (PFFS), and regional PPO (RPPO) plans. We excluded Medicare Cost plans, Medicare-Medicaid plans (MMPs), and MSA plans.

- We considered plans that covered both medical and prescription drug benefits (MA-PD). We excluded plans that offered medical benefits only (MA-only).

- We excluded plans in Puerto Rico.

We accounted for plan crosswalks by evaluating premium and membership changes as if the crosswalk plan and the receiving plan were the same. This allowed us to capture premium changes from the member’s perspective.

This study focuses only on the impact of adding a premium to a plan that had a zero-dollar premium in the prior year. It is possible that some plans also enhanced benefits at the same time the premium increased, while other plans held benefits the same (or perhaps even reduced benefits) with the premium increase. While benefit changes surely have an impact on member behavior, this article focuses only on the change in premium and the resulting change in membership, without regard to how the benefits also changed.

BRADLEY J. PIPER, MAAA, FSA, and MARY L. GABE, MAAA, FSA, are consulting actuaries with Milliman.

This article represents the viewpoints and opinions of the authors and does not represent the opinion of Milliman.