By David A. Quinn

A medical loss ratio (MLR) measures the portion of premium revenue spent on claims. It is calculated differently depending on the health insurance product and accompanying regulations. For Medicaid managed care, a state pays health insurance plans a capitation rate to cover the medical benefit and care management of the state’s Medicaid beneficiaries. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is the federal regulatory body of Medicaid and requires MLR reporting from Medicaid managed care plans and states. This Medicaid MLR adoption came with reporting challenges like accounting for special provider reimbursements or flexible remittance calculations.

States and CMS have now collected and summarized MLRs since 2017. This MLR reporting may allow actuaries to explore and inform federal and state Medicaid policy.

Adopting Medical Loss Ratios

Other health insurance products required minimum MLRs before Medicaid. The Affordable Care Act required private health insurance markets to adopt minimum MLRs in 2012.[1] Then CMS required minimum MLRs for Medicare Advantage plans in 2014 and MLR reporting for Medicaid in 2017.[2][3]

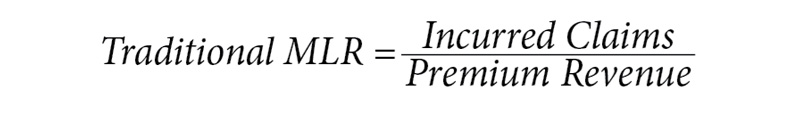

Simply, a health plan’s MLR calculation is the ratio of incurred claims over premium revenue for those claims. The more premiums a health plan spends on claims, the higher the MLR; the less premiums it spends on claims, the lower the MLR. Health plans’ MLR levels matter because federal and sometimes state government regulations require health plans to act if their MLRs are lower than a minimum MLR threshold—usually by returning premiums. In Medicaid, these returned premiums, or capitation payments, are called remittances.

The Medicaid MLR calculation is modified to account for different costs like health care quality improvement (HCQI) and taxes:

MLRs differ by health product because each product: 1) calculates MLRs using different adjustment; 2) follows different regulations; and 3) provides different covered benefits. For example, when plans report their Medicaid MLRs, they may contain the following regulatory adjustments:

Numerator Adjustments

- HCQI—These costs intend to improve Medicaid beneficiaries’ health quality; they are not claims.[4]

- Fraud Recovery—The lesser of the plan’s fraud recoveries or the costs of pursuing those recoveries.[5]

Denominator Adjustments

- Risk Adjustment—For states that deploy health status-based risk adjustment, plans report premium revenue after their risk adjustments.

- One-time Payments—Some states include one-time payments to plans, like maternity payments that cover a beneficiary’s pre- and postpartum costs. These payments constitute premium revenue.[6][7]

- Taxes—Federal, state, and local taxes are subtracted from the denominator, increasing MLR results.[8] For example, taxes on plans’ premiums, income, or member counts may be subtracted. Payroll taxes paid by the employer, like Social Security and Medicare, cannot be subtracted.

Numerator and Denominator Adjustments

- Pass-through Payments—These payments are non-risk money that states require and actuaries fund in capitation rates to plans but are predestined for plans to pay to providers in the arrangement. Pass-through payments are excluded from the MLR but sometimes are misidentified by plans.[9]

- Credibility Adjustment—A percentage point statistical credibility adjustment added to smaller plans’ MLRs based on Medicaid membership and population like acute care versus long-term care.[10]

The private market and Medicare Advantage have required minimum MLR thresholds of around 80%-85%, depending on the product and state.[11] If an MLR is below that threshold, the plan returns some premium to policyholders. But in Medicaid, states can optionally require MLRs. If states do require minimum MLRs, the threshold must be at least 85%.[12] Plans with MLRs below the minimum owe the state a remittance.[13][14]

These Medicaid MLR options give states flexibility. Because using a minimum MLR is under state authority and optional, so too is the remittance formula decided by the state.[15] States could even put in their Medicaid contracts the option to waive an otherwise owed remittance.[16]

Learning from MLR Reporting

Effective 2017, Medicaid managed care plans were required to report their MLRs annually for each combination of state and contract they operate.[3] Similarly, CMS requires states to report annual summaries of these MLRs to them.[17] Plans report to the state; states report to CMS.

These reporting requirements lack a national template for how states collect Medicaid MLR information from their plans.[18] So states had to design custom MLR reporting and instructions; this process was new to both states and plans.

But states and plans have learned some lessons from these new reporting processes.

Counting Low-Risk Funding

State Medicaid programs have a history of making supplemental payments. Supplemental payments are provider payments above feeforservice (FFS) or plan reimbursement levels. They evolved into pass-through payments as Medicaid shifted from a delivery model of FFS to managed care.[19] Recently, pass-through payments have—or are in the process of being—converted into state directed payments (SDP) because CMS put an expiration on pass-through payments.[20]

An SDP allows a state to direct how plans reimburse providers, similar to a pass-through payment. Because the payment is passed through the plan, the plan holds little, if any, financial risk for this money. The Medicaid MLR calculation excludes pass-through payments—but not SDPs.[21] Medicaid plans recognize both types of payments as low risk but sometimes forget to exclude pass-through payments or exclude too much by excluding any low-risk money, like SDPs.

States often convert expiring pass-through payments into SDPs. These new payments would be in the MLR denominator as premium revenue and in the numerator as claims paid to providers. This result pushes the MLR calculation toward 100%, increasing a plan’s odds of meeting the minimum MLR. Some SDPs are paid or reconciled after a rating period.[22] If this process takes almost a year or more, plans will have to estimate their SDP share for MLR reporting, adding uncertainty to plans’ MLR results.

States have been increasing their use of SDPs and the volume of money they direct.[23] It is possible CMS will revise SDP regulation, including whether plans can include SDPs in Medicaid MLRs. States also have flexibility in their remittance formulas and may decide to include or exclude SDPs as part of the calculation.

Adjusting the Underwriting Gain Component

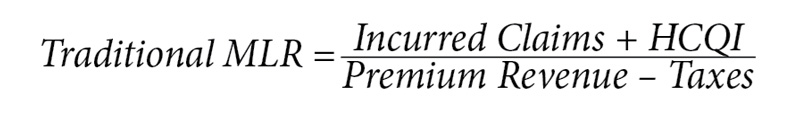

The underwriting gain component provides plans with a cost-of-capital component and a margin for risk.[24] Its calculation typically considers a plan’s risk profile but also can target an expected net income. Income and MLRs are inversely correlated: the less premiums a plan spends on claims, the lower its MLR.

States can require plans to pay a remittance if the state’s minimum Medicaid MLR is unmet.[13] This remittance effectively becomes a cap on a plan’s net income because additional net income will lower its MLR, and any additional amount below the minimum MLR will be remitted. Statistically, this cap lowers a plan’s expected net income. So if a state’s actuary wishes to keep the same expected net income as before the remittance requirement, the actuary must increase the underwriting gain component.

In 2022, the Society of Actuaries (SOA) released a model for calculating underwriting gain components. It has a feature to adjust the underwriting gain component for this type of MLR interaction.[25] States and their actuaries might revisit their underwriting gain component assumptions if a remittance is required and measure its effect on plans’ expected net income.

Withholding Capitation

In its 2016 regulation update, CMS defined the term “withhold” as an arrangement where the state withholds some capitation unless a plan meets contractual state goals.[26]

Before this definition, the term was undefined in regulation. Some states used the term “paper withhold” to describe plan premiums paid for risk mitigation, like a risk corridor or risk pool. This paper withhold occurs when a state settles risk-migration premiums and receipts in a single net calculation instead of collecting premiums in one transaction and then paying receipts in another.

Plans sometimes confuse the risk-mitigation withhold terminology with how regulatory withholds should be reported in the Medicaid MLR.[27] The federal regulation discusses withholds near the net payments or receipts related to risk mitigation, so the old and new withhold terminologies get conflated. Thus, a plan could accidentally double-count risk-mitigation premiums by calling them a withhold payment. The plan would artificially lower its MLR and may accidentally trigger a remittance.

States may revisit how they use the term “withhold” and limit their use to only the regulatory definition to avoid reporting confusion.

Considering Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

Community characteristics, infrastructure access, and other social opportunities are types of SDOH. CMS has encouraged states to address SDOH through Medicaid to promote quality health outcomes.[28] Plans’ costs for addressing SDOH could be for non-covered services and thus excluded from the cost data actuaries use to calculate future capitation rates.[29] However, plans can sometimes count some of these costs as HCQI, which gives them credit in their MLR numerators, increasing their MLR and lowering the odds of owing a remittance.4 Nevertheless, the MLR misses an incentive nuance.

Suppose a plan’s SDOH initiatives work. The plan will likely get a return on investment via lower claim costs. If claim savings are more than the SDOH costs, then even with HCQI numerator credit, the plan nets a lower MLR putting the plan closer to a remittance. This move toward remittance may create a disincentive for plans to engage in SDOH initiatives or similar non-covered management services.

To overcome this disincentive, states might look to characterize some SDOH as in lieu of services (ILOS).[30] If SDOH costs can be characterized as an ILOS, then actuaries can include them in the cost data for capitation rate setting.[31] Plans can continue to count it in their MLR numerators too. States might also consider a quality component to their remittance formula. For example, if a plan owes a remittance, but meets state quality goals, the state waives the remittance to incentivize the plan’s quality initiatives.

Owning Plans and Providers

Providers can own managed care health plans and plans can own their providers. These entity relationships can obscure underlying Medicaid MLR performance reported to the state by shifting costs and targeting internal MLRs.

For similar reasons, the Medicaid MLR regulation is written with the term “direct claims” and omits any reference to the term “reinsurance.”[32] Commercial reinsurance is not allowed in the Medicaid MLR calculation.[33]

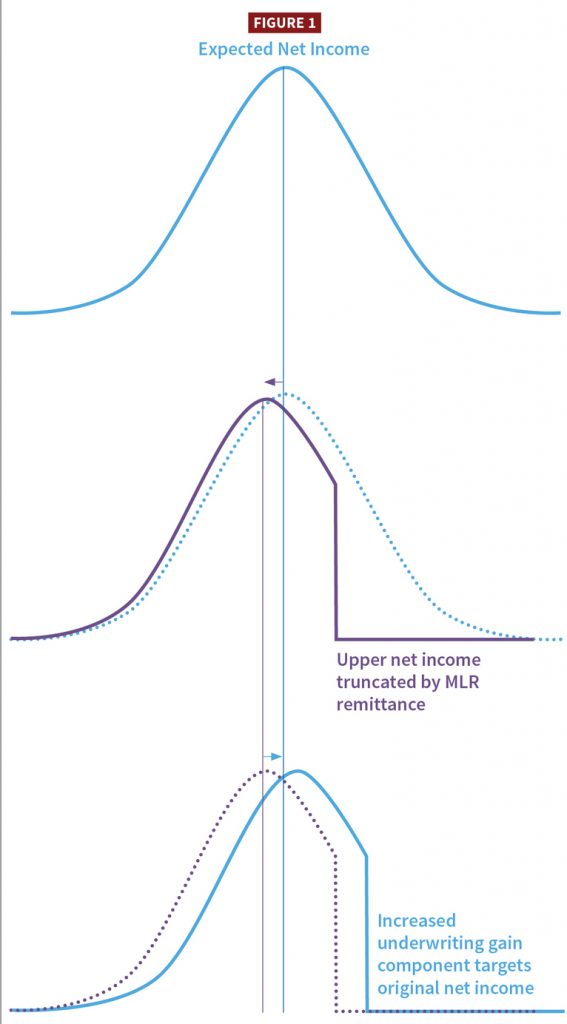

But suppose commercial reinsurance were allowed. Imagine Plan A was likely to owe a remittance for the MLR reporting year. Another plan—Plan B—has higher MLR experience and is unlikely to owe a remittance. Plan B could rent its higher MLR to Plan A with quota share reinsurance. Plan A bolsters its low MLR above the minimum MLR threshold to avoid owing a remittance, and Plan B collects economic rent. Table 1 shows an example assuming an 85% minimum MLR threshold.

The provider-plan relationship can act like quota share reinsurance but is called a value-based purchasing or alternative payment arrangement instead. The plan and provider are a financial ballast for each other’s performance. The plan’s Medicaid MLRs appear more stable year-over-year than other plans. Any low claims experience lowering the MLR are bolstered by shunting expenses to the related entity and reporting it in the MLR as incentives payments to network providers.[34] The outcome is these plans avoid paying remittances they might otherwise owe absent a related-entity relationship.

States may wish to consider how related-entity relationships are factored into remittance formulas.

Divvying Up Remittance

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), another joint federal-state program, follows the same MLR regulations as Medicaid.[35] CHIP serves children of families with incomes higher than Medicaid and can require premiums from higher-income beneficiaries.[36] If states require an MLR remittance on CHIP, beneficiary premiums complicate the process.

States can deliver CHIP through a managed care system. CHIP plans cover beneficiaries’ health needs funded by revenue from state capitation and beneficiaries’ premiums. Premiums can vary by income level, with the state paying the difference via capitation. Some CHIP beneficiaries pay nothing, while others may pay the entire premium (no state capitation). These premium tiers present a challenge often absent from Medicaid. If there’s a CHIP plan remittance, how much do beneficiaries get versus the state and CMS?

The easiest solution is for a state to forgo the CHIP MLR remittance requirement. But that choice may be unpopular with any group wanting cost controls on government health insurance.

Suppose a state requires a CHIP MLR remittance. It would be helpful if CHIP plans reported MLRs by premium tier. States can require reporting detail by any population subtotal under the contract.[37] Here are example tiers and their remittance treatment:

- For a CHIP tier with no beneficiary premium, remittance would return to only the state and then be shared with CMS.

- For a low-cost program (beneficiaries and the state both pay), there could be a three-way split on the remittance (beneficiaries, state, and CMS).

- For a full-buy program, CHIP plans return any remittance owed to beneficiaries that bore the program cost. Technically this tier is exempt from the CHIP MLR requirements because no federal dollars are involved.

Another helpful design choice is to have CHIP plans report beneficiary premiums separately from state capitation. No national Medicaid MLR template exists for plans to report to states, so states created custom reporting. One design choice was to itemize the CMS regulation and have plans report amounts for each regulatory description (HCQI, premium revenue, taxes, and so forth). However, CHIP MLR regulations directly reference the Medicaid regulations, which forgo any mention of beneficiary premiums. Thus, including a CHIP premium reporting line would help parse a state versus beneficiary remittance.[38]

Attaching MLRs to Risk-Corridors

Some states tie MLR performance to risk corridors. These corridor arrangements can act like remittances—capping net income based on tiers of MLR thresholds. Suppose a state revisits its MLR remittance formula and has an MLR-based risk corridor. In that case, the state may want to sync the two MLRs formulas to preserve plan incentives. For example, if the state counts HCQI in the MLR numerator for remittance, it may wish to allow HCQI to be counted for the risk corridor too. Otherwise, the state may fail to incentivize a change from its plans. What might be an incentive in one setting is a disincentive in the other.

Reporting MLRs

Using Web-based Reports

Plans report MLRs to states annually, and states submit a summary of those to CMS.14 In 2021, CMS announced it was working on new MLR web-based reporting templates.[39] In 2022, CMS shared Excel template drafts of that web-based interface.[40] Currently, states are exploring how to populate these templates because CMS will require their use for Medicaid rate certification packages on or after October 1, 2022.If more Medicaid MLR data is available in a uniform format, the opportunity for actuaries to explore this nationwide data may help states and CMS further design their Medicaid and CHIP programs. For example, this data could help develop a pediatric statistical credibility adjustment for CHIP MLRs. It could also inform how states set their minimum MLR thresholds or calculate expected remittance from different remittance formulas.

Overseeing Medicaid MLRs

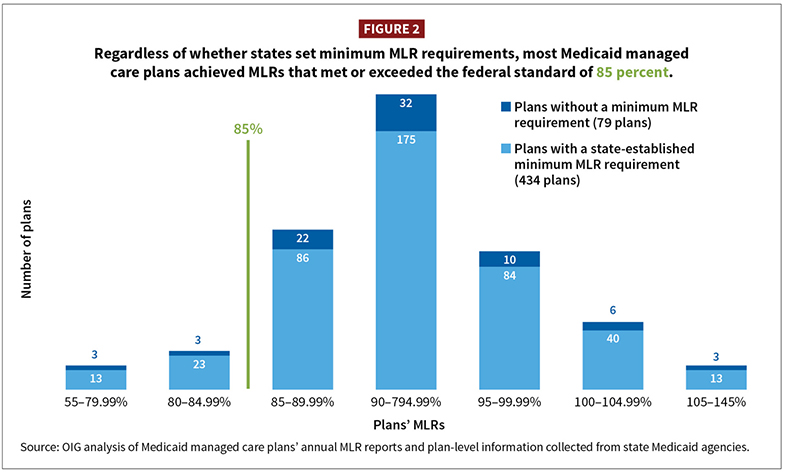

In 2021, the U.S. Office of Inspector General (OIG) reported its study of Medicaid MLR performance for the first three years of reporting (2017–2019).[41] For states with remittance requirements, 91% (395 of 434) of plans met the minimum 85% threshold.

These plans’ median Medicaid MLR was 93%. As mentioned earlier, the Medicaid MLR is adjusted for costs like HCQI and taxes. For those same three years, using plan data from the SOA 2022 Underwriting Margin model, plans averaged a traditional MLR of 88%.[42] The 5% point increase between the OIG-reported 93% Medicaid MLR and the SOA 88% traditional MLR highlights the effect of these different MLR formulas.

OIG called its report “Almost All Medicaid Managed Care Plans Achieved Their Medical Loss Ratio Targets.” States may have noticed this performance too. A plan median MLR of 93% leaves several percentage points for plans to increase net income and still meet the 85% minimum: It’s a generous MLR.

States probably have a tacit expectation of what net income amount should trigger a remittance. And state budget offices may be looking for Medicaid savings because they face economic uncertainty and the loss of enhanced federal funding when the public health emergency related to COVID-19 ends.[43] These conditions may lead states to adjust their MLR thresholds or remittance calculations if they feel a disconnect between plans’ net incomes and MLR performance.

Outro

CMS required Medicaid MLR reporting after the private market and Medicare adopted minimum MLRs. States with Medicaid managed care have had to create custom MLR reporting to collect their Medicaid plans’ MLRs. Along with states, plans have learned reporting lessons as Medicaid has risk-mitigation layers and provider reimbursement that complicate MLR reporting. States have the option to require a remittance from plans with MLRs below a minimum threshold. These states may want to consider how their custom remittance formula interacts with SDPs, withholds, SDOH, and related-entity relationships. CMS is testing a tool for state MLR data collection. More MLR data allows actuaries to explore Medicaid plan performance and help inform how states or CMS might evolve Medicaid MLRs.

DAVID A. QUINN, MAAA, FSA, is a principal actuary at Mercer Government Human Services Consulting (Mercer). This article represents the viewpoints and opinions of the author and does not represent the opinion of Mercer. He also wishes to acknowledge F. Kevin Russell, MAAA, FSA, for his draft review and feedback.

References

[1] “Medical Loss Ratio”; CMS.gov. [2] “Medical Loss Ratio”; CMS.gov; December 2021. [3] “42 CFR § 438.8—Medical loss ratio (MLR) standards”; eCFR; December 2020. [4] “45 CFR § 158.150(b).” [5] “42 CFR § 438.8(e)(2)(iii)(B).” [6] One-time payments are sometimes referred to as kick payments. [7] “42 CFR § 438.8(f)(2)(ii)v.” [8] Also includes licensing and regulatory fees; “42 CFR § 438.8(f)(3).” [9] “42 CFR § 438.8(e)(2)(v)(C).” [10] “Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Credibility Adjustments”; CMS; July 2017. [11] For example, New York has a minimum MLR of 82% for some products. [12] “42 CFR § 438.8(c).” [13] “42 CFR § 438.8(j).” [14] Per 42 CFR § 438.74, If a state collects a remittance, then it must return a portion of it back to CMS based on the state’s Federal medical assistance percentage. [15] “Medicaid Managed Care Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)—Medical Loss Ratio,” page 8; CMS; June 2020. [16] “Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Programs; Medicaid Managed Care, CHIP Delivered in Managed Care, and Revisions Related to Third Party Liability”; CMS; Federal Register; May 2016. [17] “42 CFR § 438.74.” [18] CMS is prototyping a template for how states report Medicaid MLRs to CMS. However, states still have to design their reports for getting the plans’ Medicaid MLRs to begin with. But, at the time of writing, the OIG recommended that CMS create a national report states could share with their plans to collect Medicaid MLRs. Some states accidentally omitted required Medicaid MLR data from their custom reports. “CMS Has Opportunities To Strengthen States’ Oversight of Medicaid Managed Care Plans’ Reporting of Medical Loss Ratios,” page 9; OIG; September 2022. [19] “Directed Payments in Medicaid Managed Care,” pages 1-2; MACPAC; June 2022. [20] “42 CFR §§ 438.6(d)(3), 438.6(d)(5).” [21] “42 CFR § 438.8(e)(2)(v)(C).” [22] “The separate payment term is captured in the applicable actuarial rate certification that the state submits for its capitation rates. However, the directed payment is made separately to the managed care plans from the capitation rates paid to plans.” GAO letter to Senate Finance Committee, House Energy & Commerce Committee, and House Oversight and Reform Committee; June 28, 2022; Footnote No. 12. [23] “Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP,” page 45; MACPAC; June 2022. [24] “Actuarial Standard of Practice No. 49, Medicaid Managed Care Capitation Rate Development and Certification, section 3.2.12.b”; Actuarial Standards Board; March 2015. [25] “Medicaid Managed Care Underwriting Margin Mode,” page 40; SOA; June 2022. [26] “42 CFR § 438.6(a) ‘Withhold arrangement.’” [27] “42 CFR § 438.8(f)(2)(iii).” [28] “Address the Social Determinants of Health to Improve Outcomes, Lower Costs, Support State Value-Based Care Strategies”; CMS; January 2021. [29] “42 CFR 438.3(e)(1)(i).” [30] For example, California is calling some SDOH costs as ILOS. [31] “42 CFR 438.3(e)(2)(iv).” [32] “42 CFR § 438.8(e)(2)(i)(A).” [33] However, state stop loss is allowed. For example, the state Medicaid program could have retained financial responsibility for annual claims in excess of $500,000 per person, so that any expected excess was not included in the capitation rates. The health plan could pay the entire claim and then request reimbursement for the amount beyond the $500,000 per person. [34] The sign can be positive or negative depending on which direction the money flows between plan and provider. “42 CFR § 438.8(e)(2)(iii)(A).” [35] “42 CFR § 457.1203(f).” [36] “Program History”; Medicaid.gov. [37] “42 CFR 438.8(i).” [38] A beneficiary premium report could also help CHIP MLR accuracy if a state uses an itemized Medicaid MLR design for reporting, and then the CHIP plans report MLRs with beneficiary premiums missing from the denominator. The issue would quickly reveal itself if plans reported spate premium tiers and premium revenue for the full-buy (no state capitation) tier was zero. [39] “Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care Monitoring and Oversight Tools”; CMS. [40] “Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Report”; Medicaid.gov. [41] “Nationwide, Almost All Medicaid Managed Care Plans Achieved Their Medical Loss Ratio Targets”; OIG; August 2021. [42] “The MLR was calculated as the sum of Total Hospital and Medical Expenses and Increase in Reserves, divided by Total Revenue. The PMPM Revenue was calculated by dividing the Total Revenue by the Total Member Months,” page 32-33; Medicaid Managed Care Underwriting Margin Model; SOA; June 2022. [43] “Families First Coronavirus Response Act, Section 6008.”