By Joe Allbright, Tomonori Hasegawa, Alex Leung, Susan Mateja, Stuart Rodger, and Zerong Yu

Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a series of articles from the Health Practice International Committee on ideas from foreign models of health care that may assist the United States in finding cost-effective ways to deliver high-quality health care in an equitable and sustainable way.

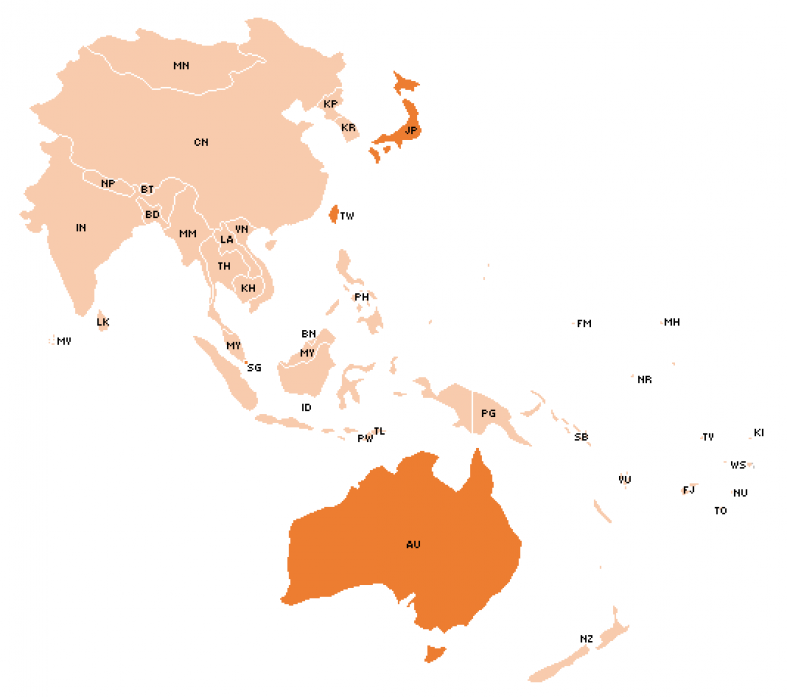

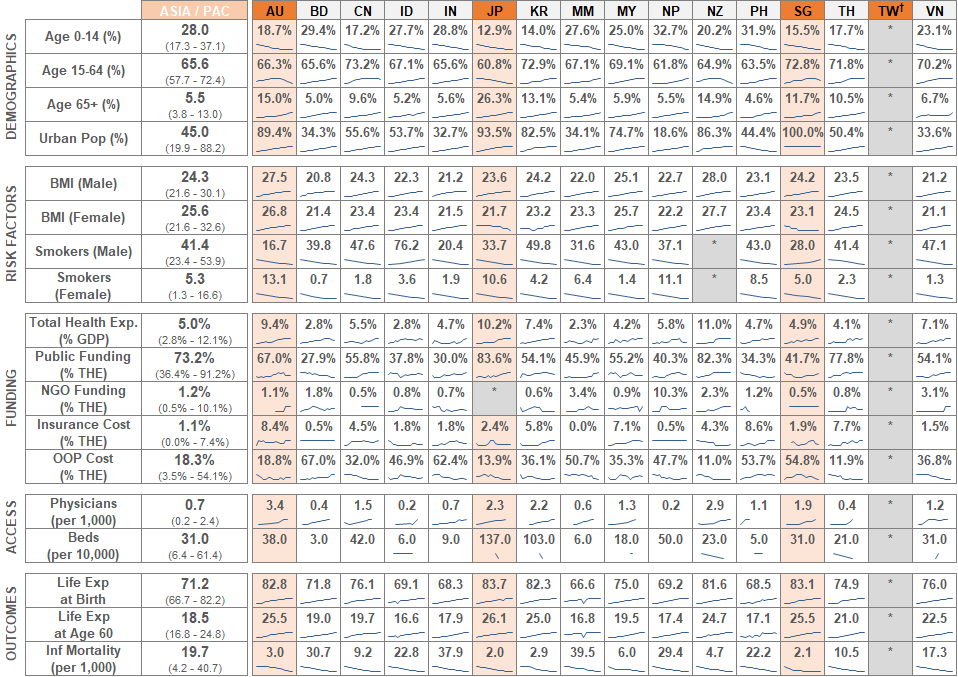

The countries in Asia and the Pacific have seen major cultural shifts in the past 50 years. New technologies, aging populations, new wealth, and the increased separation of metropolitan and rural areas all present their own health care challenges and opportunities. While none of the health systems we discuss here are necessarily new, they have all experienced significant changes over the past 30 years as they adapt to the changing needs of their citizens.

Taiwan

Taiwan, with a population of over 23 million and a total area of 36,000 square kilometers, is one of the most densely populated areas in Asia. Over the past 60 years, it has quickly emerged as one of the more advanced economies in Asia as it rapidly transitioned from an agricultural-based economy to one based predominately on services and industries. This escalating economic growth as well as social concerns for the large, uninsured population led the Taiwanese government to start planning for a universal health insurance program in the 1980s. After years of studying health systems around the world, the National Health Insurance (NHI) was eventually adopted in 1995 to consolidate the previously fragmented labor insurance market and to extend health care coverage to all. The program provides a comprehensive benefit package and covers more than 99 percent of Taiwan’s current population, a significant improvement from the 59 percent that was previously covered by the various labor insurance schemes.[1]

The NHI is administered by the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA), the quasi-government insurer and single payer for the program. While the primary funding for the NHI benefits is provided by income-based premiums, the NHIA operations are financed through an administrative budget allocated by the government. The administration is highly regarded for its remarkable efficiency and low administrative costs, which have been kept at below 2 percent of the NHI’s total budget in recent years. This low overhead ratio reflects, in part, the administrative efficiency that the NHIA has gained with its technology-enabled processes and procedures.

Taiwan has a robust information technology (IT) infrastructure that underpins the various administrative functions of the NHI program. This interconnected network of IT services supports the operations of provider payment, medical records management, enrollment application, and eligibility verification. Many of its automated processes enable quality improvement and promote system-wide efficiency by running administrative tasks that were once handled manually, which minimizes the transaction and administrative costs in the health system. For example, the Integrated Circuit Smart Card (IC card) is the technology that integrates many of the disjoint NHI services into a single, integrated platform. The IC card stores four types of patient information—personal information, NHI-related information, medical service information, and health administration information—and enables medical providers to submit electronic records on a daily basis to the NHIA. This data is stored in a medical information system, and the daily feed enables the NHIA to monitor medical service utilization, prevent fraud from aberrant claims, and scan for potential disease outbreaks in real time.

With the technology advancement over the last decade, the NHIA has introduced a new online portal, the PharmaCloud, to offer cloud-based storage and access of medical records. In particular, the PharmaCloud provides physicians and pharmacists online access to patient medication history from the three most recent months. As there were no established channels for sharing patient medical records among providers prior to the PharmaCloud, patients were at risk of receiving repetitive or conflicting prescriptions from different providers; this was a prevalent problem as “doctor-shopping” is a highly common practice in Taiwan. The new portal not only helps improve patient safety as it relates to overmedication and adverse drug interactions, but it is also an important step toward eliminating medical waste in the health system.

The NHI premiums are based on a progressive contribution schedule, and it has been adjusted only three times over the past two decades. On average, the rate was 4.25 percent of income at NHI’s inception. It was then raised to 4.55 percent and 5.17 percent in 2002 and 2010, respectively, to address a growing deficit under the program. In particular, the rise of health care expenditures had outpaced that of revenue as early as 1998. With the rate adjustments, the program eventually recovered from its deficit at the beginning of 2012 and has remained in surplus since. In 2013, the rate was reduced to 4.91 percent to balance with the expanded source of revenue granted by the second health reform. The expanded source includes a supplementary premium that is 2 percent of non-regular income, such as high bonuses, wages from part-time jobs, ad hoc professional fees, interest income, stock dividends, and rental income, that were not considered under the previous system.

In response to the deficit problem that began in 1998, the NHIA quickly established a global budgeting system to manage the rapidly increasing health care expenditure. In designing the system, the NHIA studied and borrowed from the experience of Canada and Germany. Between 1998 and 2002, expenditure caps were phased in for four health care service sectors: dental (1998), traditional Chinese medicine (2000), Western medicine clinics (2001), and hospitals (2002). Since then, a separate budget for end-stage renal disease has also been allotted under the global budget. The global budgeting system has been credited as an effective cost containment mechanism that managed Taiwan’s health care expenditure growth to 3 to 5 percent annually without compromising medical quality.

The NHI ensures equitable access to its enrollees by maintaining an expansive provider network. All licensed and accredited providers can be contracted, provided that they do not have a disqualifying event. More than 93 percent of all providers in Taiwan are contracted by the NHIA. Of the remaining non-contracted providers, most have chosen to operate without accepting the NHI. These providers, such as renowned cosmetic surgeons and Chinese medicine doctors, sustain their operation through a high volume of profitable, self-pay patients who are attracted to the providers’ highly regarded reputation.

Japan

Japanese citizens are well educated (50 percent go to college level), enjoy a high income per capita ($42,700 U.S. in 2017)[2] and a healthy lifestyle. Life expectancy in Japan is one of the longest in the world, and the rate of population growth is among the lowest. Total fertility rate is 1.44 births per woman, well below the level needed to sustain the present population. Since 2007, Japan’s total population has been decreasing. This low fertility rate, and to a lesser extent the increasing life expectancy, has resulted in a rapid aging of Japanese society; those aged 65 or over now make up 26.3 percent of the population. As one of the first countries to experience this significant demographic change, Japan is in a position to instruct other nations on how to face the challenges of an aging society. Other countries, including many in Southeast Asia, are expected to see similar aging within the next 20 to 40 years.

Japan established universal health coverage (UHC) for medical services in 1961. This was comprised of two parts—the Employees Medical Insurance (EMI) scheme for employees and their families and the National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme for the self-employed, unemployed, and retired/elderly. The EMI is funded by both the employer and employee contributions, and covers 70 to 80 percent of the cost of care. The NHI, while still requiring the member to pay a premium, is largely funded by central and municipal governments. As employees retire, they move from the EMI program into NHI; because the elderly required a greater level of care and were able to contribute less in premiums, the NHI was operating at a large deficit. In 1982, a Health Service Law for the Elderly was passed that created a fund in each municipality to finance elderly households in the NHI. This fund draws from the EMI and NHI programs as well as from national and local government revenue.

There are about 8,500 hospitals and 100,000 clinics in Japan. This high number of health service providers and UHC guarantee adequate access to providers. Still, the Japanese health care system has several challenges including shortage and maldistribution of physicians, long working hours, and quality and safety issues. In late 1990s, severe lethal adverse events in renowned teaching hospitals were reported, and regulations concerning quality and safety were strengthened.

Easy access is likely to produce overuse of health care services, and elderly people with limited income cannot afford to pay for the premium. While many medical needs were covered by NHI, services at nursing and home care services were not. This created an incentive for aged individuals without family support to seek hospitalization rather than paying out of pocket or applying for welfare services. In 2000, Japan introduced a mandatory long-term care insurance (LTCI) program to address this issue.[3] This program uses a detailed questionnaire to determine eligibility and the level of care needed. Programs emphasize home- and community-based services over hospitalization.

Public medical care and LTCI were originally designed as social insurance, but now the government financially supports them through taxation. The control of health expenditures has been a major objective of the health sector reforms Japan witnessed in recent years, though this has not yet been fully achieved. Increase of value-added tax rate to pay for these rising costs has not been widely accepted, and has become a major social concern. With aging population and financial limitation of the government, the sustainability of UHC has often been a matter of serious debate. Japan is committed to maintaining the UHC largely because no other system is considered to be as cost-effective.

While Japan’s health care outcomes are certainly among the world’s best, there are still areas room for improvement, especially around cost. Measures could be considered to improve cost transparency, cover routine services, facilitate Big Data analysis through portable ID numbers, and increase out-of-pocket payments or coverage limits. The decisions Japan faces now are ones that much of the developed world will soon be confronted with, and how that country responds to these challenges may have global echoes.

Singapore

With one of the highest GDPs per capita in the world,[4] Singapore also enjoys a world-class health care system. Singapore’s overall health care spend is only 4.9 percent of its GDP,[5] half of the typical range for most developed countries,[6] and roughly a quarter of U.S. spend of 17.1 percent of GDP.[5] Despite the low cost of health care, Singapore’s outcomes are among the best. In the most recent released 10th annual global “Prosperity Index” by Legatum Institute, Singapore is ranked No. 2 as the healthiest country in the world,[7] making Singapore’s health care delivery system one of the most efficient around the globe.

Singapore offers universal health care to all citizens in the country. Prevention, healthy lifestyle, and wellbeing have long been promoted in the culture and through government programs. The system emphasizes on individual accountability as well as affordable health care for all. Individual responsibility is reflected in relatively high levels of out-of-pocket spending of 54.8 percent of total health care spend. These principles are also carried out by a “3Ms” system—Medisave, Medishield, and Medifund.

- Medisave is a mandatory personal medical savings program, with contribution rates ranging from 7 to 9 percent of pay. It is matched by funds contributed by employers. This allows the population to build up savings for future health care needs for themselves and their immediate family members.

- Medishield is a catastrophic health insurance program, protecting against major medical expenditure. While individuals bear the cost of routine care, all citizens are enrolled automatically in Medishield for larger, unplanned expenses.

- Medifund is designed as a social safety net for Singaporeans unable to afford the care they need. The amount of assistance provided depends on income and social circumstances.

Besides government health insurance programs, supplemental private health insurance policies are also available, usually through employers. Patients can choose any providers within the government health care system. No appointment is needed for a consultation or emergency services.

Singapore’s government, through the Ministry of Health, plays a critical role in setting policy and financing, and maintaining the health care system. Besides heavily relying on medical savings accounts and cost sharing to control expenditure, government regulation also plays a critical role in keeping the system running efficiently. The Ministry of Health can manage the supply and cost of medical services through its direct control of public hospitals. As so much of the cost is paid for by the patient, private providers who charge too high over the public hospitals tend to price themselves out of the market. On the demand side, multiple mechanisms are used to avoid unnecessary medical service use including copays, deductibles, and restrictions on the use of Medisave and Medishield for certain services. The cost for medical services is publicly available for everyone to see. Additional savings are generated by negotiating and purchasing drugs and medical supplies at a national level.

The national health care system in Singapore is not without its challenges. With its aging population and a low birthrate of 1.20 per woman,[8] health care costs are expected to trend higher. The system needs to develop strategies to address the health care needs of the elderly. Though Singapore’s emphasis on individual responsibility has lowered costs overall, there remains a heavy financial burden on the segment of the population who experience severe adverse health events. There is not currently a robust mechanism for resource transfer among individuals. Although Medishield can cover catastrophic events, there is still significant risk pooling need for non-catastrophic illness because a Medisave account can be depleted with a single episode of illness. More risk pooling will help develop a more equitable system.

Singapore’s health system is a successful demonstration of pragmatism. The health care system combines both conservative and liberal economic principles. The government has a strong role as an agent to tightly control the cost, using its unique position to regulate, negotiate, as well as to provide for those in need. Nonetheless, individual responsibility is fostered through medical savings programs and high level of out–of-pocket cost. In Singapore, both the government and the citizens play a critical role in creating a sustainable and efficient health care system.

Australia

Australia has one of the world’s highest life expectancies, behind only Japan, Switzerland, and Singapore. The health system offers universal access, while also maintaining a strong private sector component. All Australians are covered by Medicare, which reimburses a part of the cost for any doctor service, provided they are Medicare-accredited and the service is included within the extremely comprehensive Medicare Benefits Schedule.

Every Australian is guaranteed access to the public hospital system completely free of charge, but there are waiting periods required for many services. In addition, about 45 percent of Australians hold some form of private health insurance (PHI) covering private hospital treatment. PHI gives policyholders a choice between using the public hospital system or the private system where they can also choose their own doctor. As a result, a significant proportion of hospital episodes take place in the private sector, although the majority are in the public hospitals. The high level of private insurance for hospital coverage is driven by government policies, requiring premiums to be community-rated, backed by a mandated risk equalization system. Other government policies to support the adoption of health insurance include a means-tested tax rebate on health insurance premiums and an additional tax payable above a certain level of income if no insurance is held.

The public hospital system is operated by each Australian state, but a large part of the funding for this is provided to the states by the commonwealth government, through a series of commonwealth/state financial agreements which are renegotiated every five years. These agreements include the guarantee of access for all Australians. Access can be a challenge in Australia, however, as shown by disparities in health services available in metropolitan versus rural areas, leaving those in remote areas with mortality rates 1.4 times higher than that of those in major cities.[9] Australia has pursued specific initiatives to improve health among Australia’s indigenous populations (where life expectancy is unacceptably low).

While public hospital costs are free for those with Medicare, medical visits outside a hospital may carry a cost. Australia maintains a schedule of benefits, and Medicare will reimburse up to 100 percent of that amount for general practitioners, and up to 85 percent for specialists. Private coverage is available to make up the gap between Medicare reimbursement and the full charge. There are also private coverages for dental, vision, home health, and ambulance services.

Both the out-of-pocket costs and the shift to private coverage help to keep the government health care burden low. As of 2015, 9.4 percent of the Australian GDP was spent on health; this is near to the OECD average. Of this, most came through commonwealth (41 percent) and state (26 percent) governments. Individuals paid 17 percent directly, and another 9 percent through their direct PHI payments. The remaining 7 percent is from other sources such as workers’ compensation. With three-quarters of the premium paid by policyholders and the remaining quarter from government support, overall private health insurers mobilized 12 percent of total costs[10]

Cost growth is an issue, both for government budgets and for consumers who are experiencing annual growth in health insurance premiums. The commonwealth government Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme applies cost controls to a wide range of approved drugs, acting in a way as a national wholesaler. Schedule fees under Medicare are also subject to government control, but medical practitioners are allowed to charge more than this level, so this is only a partial control.

Lessons for the United States

As the Baby Boomers have been retiring and moving into Medicare, the United States has had to confront the challenge of funding a separate program for the elderly. Unlike Japan, we must make the difference up through tax revenue and policy changes, as we don’t have a mechanism to divert premiums from the employer-based system. Additionally, many of the issues that encouraged Japan to introduce its LTCI program will likely occur here as Baby Boomers require more non-medical care services. The detailed eligibility and tiring of benefits may also prove to be an interesting model to explore.

The reality of electronic medical records in the United States has, in many ways, failed to live up to the initial promise of efficiency, accessibility, and security, instead fragmenting into different “walled gardens” that often fail to communicate effectively across formats. Taiwan’s national system has found ways to leverage electronic medical records to reduce cost, improve patient experience, and equip providers with critical tools to promote individual and population health goals.

Another trend in U.S. health care is “consumerism”—the idea that by sharing the cost of health care and encouraging savings, patients will make more cost-conscious choices. While health savings account-eligible high-deductible health plans try to promote consumerism, efforts are often undermined by a lack of cost transparency and an expectation that health plans cover both the catastrophic and the routine. By requiring citizens to contribute to Medisave, creating transparent prices for medical services, and promoting the idea that insurance is truly for the large and unpredictable medical expenses, Singapore may truly have a culture of medical consumers.

Australia presents a way of offering public and private systems together. There are a number of mechanisms, from tax incentives to wait times, encouraging those who can afford it to stay in the private system. State-run hospitals, reimbursement rate setting, nationally negotiated pharmaceuticals, and community-rated insurance are all aimed at controlling costs. A combination of copays and safety nets control utilization while preserving coverage for those in need.

THE AUTHORS are members of the Academy’s Health Practice International Committee.

References

[1] Health Affairs; “Taiwan’s New National Health Insurance Program: Genesis And Experience So Far”; 2003. [2] Central Intelligence Agency website; “The World Factbook: Japan”; last updated April 24, 2018. [3] International Journal of Integrated Care; “Long-Term Care Insurance and Integrated Care for the Aged in Japan”; July-September 2001. [4] Central Intelligence Agency website; “The World Factbook: GDP—Per Capita”. [5] World Health Organization. [6] OECD (2017); “Economic references (Edition 2017)”; OECD Health Statistics (database). [7] The Commonwealth Fund website; “The Singaporean Health Care System.” [8] The Straits Times; “Singapore’s Total Fertility Rate Dipped to 1.20 in 2016”; Feb. 10, 2017. [9] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Australia’s Health 2016; “5.11 Rural and Remote Health”; 2016. [10] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Health Expenditure Australia—2015-16; 2017.