Editor’s note: Welcome to Contingencies’ new department, “International Corner.” This first series will present thoughts and findings from the Health Practice International Committee on foreign models of health care to assist the United States in finding cost-effective ways to deliver high-quality health care in an equitable and sustainable way.

By Susan Mateja and Joe Allen Allbright

Each country’s health care system is a reflection of its political, medical, economic, cultural, and moral fiber. While these characteristics may not line up perfectly with those of the U.S. system, there are intersections and similarities as countries grapple with many of the same health care issues. Examples of these issues are the escalating cost of modern medicine and drugs, an aging population, new technologies, health care provision arrangements, lifestyle, rising expectations, perverse incentives, chronic morbidity, and shortage of care providers.

Countries are constantly innovating and reforming their systems. And though we believe that there is no one perfect system, we have identified useful approaches, objectives, and techniques that are worthy of consideration.

This will be the first of six “International Corner” articles. The series will focus on five geographic groupings: Europe, North America, Central/South America, Asia/Pacific, and Africa/Middle East. We recognize that even within these regions there is a wide range of approaches to heath care. Each article will include an in-depth spotlight on three to four of the countries, written by actuaries who have experience with their health care systems. These articles can be viewed as a complement to the international webcasts we have been sponsoring over the past couple years.

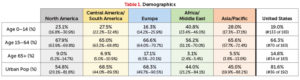

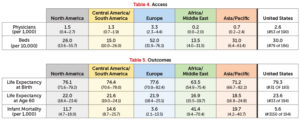

Using data from the World Health Organization’s Global Health Observatory and the World Bank, we are able to add context to each nation’s health care program. This context has been divided into demographics, risk factors, funding, access, and outcomes. The tables below highlight various health care aspects based on 2015 (or most recent available) data, with equal weighting for countries in that grouping. The median and ranges at the 10th and 90th percentiles are shown. Though shown here in aggregate, upcoming articles will present these metrics for specific countries within the geographic groupings.

Demographics

Demographics are a valuable foundation to start from as we face an aging population that is becoming more urban. We are seeing fewer communicable diseases but more chronic conditions. Japan has the oldest population, with 26 percent over the age of 65 years, followed by Italy with 22 percent. The youngest countries, with less than 2 percent of the population over the age of 65, are all in the Middle East—United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Qatar. In comparison, the United States ranks us as the 81st oldest country with 15 percent over 65, a figure that has been increasing quickly as Baby Boomers age.

Risk Factors

While demographics play a strong role in understanding population health, we also need to understand the effect of lifestyle differences among countries. The two key drivers here are obesity/malnutrition (measured through body mass index, or BMI) and the prevalence of smoking.

The proportion of smokers among the adult population has shown a marked decline over recent decades across most countries. In the United States, the adult male smoking rate in 2015 was 20 percent and the female was 15 percent—a decrease of over 30 percent since 2000. At the same time, obesity rates have increased in recent decades. In the United States, the obesity rate among adults, based on actual measures of height and weight, was 35.9 percent in 2010, up from 15 percent in 1978. Obesity’s growing prevalence foreshadows increases in the occurrence of health problems (such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases) and higher health care costs in the future. In 2014, the average U.S. adult male had a BMI of 28.9 and a female had 28.7.

Funding

Health spending accounted for 17.1 percent of GDP in the United States in 2014, up slightly from 16.9 percent in 2013. This is the highest health expenditure in the world. After the United States, the next highest Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations—widely considered fully developed, wealthy nations—are Sweden at 11.9 percent, Switzerland at 11.7 percent, France at 11.5 percent, and Germany at 11.3 percent.

Notably, the United States ranks second highest in terms of private insurance cost; South Africa is the highest at 42.9 percent. Botswana (32.8 percent), Brazil (26.8 percent), Namibia (24.5 percent), and the Bahamas (24.4 percent) are the only others with private insurance making up more than 20 percent of health care costs.

Access

Despite the relatively high level of health expenditure in the United States, there are fewer physicians per capita than in most other OECD countries. The number of curative care hospital beds in the United States was 30 per 10,000 population in 2009 (latest year available), lower than the OECD average of 51 beds. The number of hospital beds per capita has fallen over the past 25 years in the United States. This decline has coincided with a reduction in average length of stays in hospitals and an increase in outpatient surgeries.

We also see large disparities in access to health care between urban and rural areas across the globe. A country might have a good ranking for average physician and hospital bed counts, but medical resources are disproportionally concentrated in large urban cities, leaving rural area population exposed to a lack of basic health care coverage.

Outcomes

Finally, we can examine the health outcomes produced by the factors above.

Most countries have enjoyed large gains in life expectancy over the past decades. In the United States, life expectancy at birth increased by almost nine years between 1960 and 2010. In general, while the health outcomes in the United States are near the top quintile globally, they are toward the bottom when compared to OECD nations. Japan, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain are the OECD countries with the highest life expectancy, all exceeding 82 years. As of 2015, the United States has a life expectancy at birth of 79.3 years.

The country with the longest life expectancy at birth, Japan, spends 10.2 percent of its GDP (compared, recall, with 17.1 percent for the United States). So, while very low levels of funding will not allow countries to deliver even limited health services, higher levels of funding do not always translate into improved health outcomes.

We are challenged to understand why some countries have better population health outcomes, less costly systems, and broader access. How are countries balancing access, cost, quality, and choice? What are they doing to control rising health care cost trends? What reforms are being implemented to ensure a sustainable system? What can we learn from one another?

Future columns will try to answer these questions. We will share facts, observations, and learnings from various countries. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to reforming health care systems, we can learn and possibly apply other countries’ best practices to help achieve an equitable and sustainable system in the United States.

Susan Mateja, MAAA, FSA, and Joe Allen Allbright, MAAA, ASA, are members of the Academy’s Health Practice International Committee.