By Joe Allbright, Ian Duncan (United Kingdom), Christelle Dieudonné and Yann Quéré (France), and Rian de Jonge (the Netherlands)

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of articles from the Health Practice International Committee on ideas from foreign models of health care to assist the United States in finding cost-effective ways to deliver high-quality health care in an equitable and sustainable way.

Most of the countries in Europe offer either universal health care or a strong publicly funded health care option. Many of these systems were established or expanded shortly after the end of World War II, when the need for public services was high and private funds were lacking. Since then, universal coverage continued to gain momentum throughout Europe.

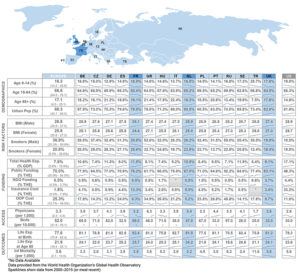

The programs are each quite different, however. Some are based on a centralized government model; others are managed locally. Some are publicly funded through tax revenue; others combine public and private contributions. Some operate as single-payer systems; others include a regulated insurance model. Patient out-of-pocket costs and covered services can also vary widely by country, creating in some a strong supplemental insurance market. Despite these differences, citizens of the European Union (and a number of non-EU nations) are provided access to other countries’ health care systems through a European Health Insurance Card program, introduced in 2004.

Many of Europe’s systems are facing long-term budgetary constraints as their population ages and birth rates decline. These programs are being modified to address costly new drugs, emerging technologies, and models to improve quality and access.

Here we will explore three of Europe’s national systems in greater detail.

United Kingdom

A National Health Service (NHS) was established in the United Kingdom in 1948. Today, the NHS operates separately in the four countries of the UK, but the service is similar throughout. This universal coverage is financed with revenue raised from general taxes, such as income tax, property tax, and sales tax. While it isn’t possible to opt out of the NHS, there is no restriction on people obtaining private health care coverage. Still, only 3.4 percent of health care costs in the UK are covered by private insurance.

The NHS has a broad but ill-defined benefits package, which includes primary care and hospital care including catastrophic coverage for intensive care and long-term medical care. These covered services require few, if any, copays and no deductibles. However, coverage excludes treatments deemed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) as being ineffective or offering poor value for the money.[1]

The organization of health care in the UK is often subject to major changes due to the priorities of the political party in power. The Health and Social Care Act of 2012[2] was the latest overhaul of the system. This reform ushered in wide-ranging reforms that were very controversial and was described as demanding “such a big change management, you could probably see it from space.”[3] These reforms emphasized competition, consumer choice, and provider plurality. The most sweeping change was the introduction of “clinical commissioning groups” dominated by general practitioners (GPs) responsible for commissioning services for the local population.

Being financed almost solely from the Treasury, the NHS is at risk from political changes that impact general funding restrictions. The NHS was over budget by 23 percent by 2013,[4] the last year for which complete data is available.

All doctors and nurses are state employees, which means that they are subject to public sector pay awards. Although there was some indication prior to the last election, in Jan. 2017, that more money might be found for the NHS staff, the most recent Treasury statement reiterated that the current public sector pay cap would stay in place. So while the government-controlled NHS has been successful at ensuring equality of access to care, it has not always been successful in ensuring quality care (indeed, the 2016 Euro Health Consumer Index shows access/wait times as a major problem in the UK). The NHS is very interested in shifting financial responsibility to providers in a manner similar to the U.S. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). A barrier to the NHS providers developing innovative solutions like the ACOs is their lack of funding.

This lack of funding has had other unfortunate results. While the NHS remains very popular with the British public, it has experienced a number of problems over recent years. One of these was the Mid-Staffordshire Hospital scandal. It has been estimated that between 400 and 1,200 patients died as a result of poor care between January 2005 and March 2009 at Stafford Hospital, a small hospital in Staffordshire. One reason for the poor care was the budgetary cuts that forced the hospital to reduce staffing. Meanwhile, changes in the financing of higher education—where the nursing training shifted from hospitals to universities—have resulted in a serious shortage of nurses. This shortage has historically been met by recruiting from the EU and abroad. However, Brexit and the change in immigration rules will have an uncertain effect on this recruitment channel.

So the centralized financing works well when the Treasury has adequate funds, but in times of budgetary constraints, the entire system suffers.

France[5,6]

The French social security system was founded in 1947 and is divided into components based on occupation. We will focus on the general scheme, which covers 80 percent of the population, but separate programs exist for agricultural workers, certain self-employed trades, and the unemployed. These programs provide health, work accident, retirement, family services, and unemployment benefits. The public health coverage is mandatory, and the level of benefits is the same regardless of occupation, which is not the case for retirement benefits. As of Jan. 1, 2016, all workers or regular residents in France are eligible for the public health coverage, without any contribution from eligible citizens in some cases.

The public health care system accounts for 78.2 percent of total health expenditure (THE). This mandatory coverage is financed by social contributions paid by employers, employees, and taxes. Retirees and the unemployed do not contribute. Expenses are not fully covered by the public system except for some long-term diseases and chronic illnesses. So individuals will pay fixed fees at the point of service unless they are classified as low-income. They may also be charged extra fees if charges exceed the social security basis.

Another 13.3 percent of THE is funded through private supplemental insurance policies. These are provided on the basis of occupation or purchased privately. There are three major types of organizations that provide private health coverage; they differ mainly by their governance:

- Mutual insurance companies (ruled by participants)—53%

- Classical private insurance companies (private insurance companies)—29%

- Joint institutions (co-ruled by workers and employers unions)—18%

Private insurance covers copayments; user fees; drugs exempt from the public system; dental, paramedical, and optical expenses; medical supplies outside hospitals; and medical and chirurgical extra fees.

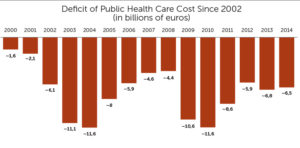

In 2015, total health expense in France made up 11.5 percent of GDP. While still well below America (at 17.1 percent), this is one of the highest rates in Europe. The public system has been chronically unbalanced since 2000. In 2006, the government implemented a stability pact in order to manage this deficit.

These reforms aim to transfer coverage from the public to private system, resulting in a decrease of the recurring health care deficiencies. However, because the private coverage has encountered a significant increase in taxation, the final out-of-pocket amount paid by individuals has already been increased.

The sustainability of the health social security system and the reduction of its deficit are still a priority for the French government, especially as health costs rise and the population ages. The French health system currently has high management costs; administrative costs represented more than 5 billion euro in 2014, or 3 percent of the global cost. Another option at improving long-term outcomes is to strengthen preventive measures to lower exposure to chronic diseases.

France is also grappling with access, especially in rural regions. This shortage is compounded by a decreasing number of students entering the medical profession. To combat this problem, France is now exploring digitizing or virtualizing physician visits.

The Netherlands[7]

Prior to 2006, the Dutch health care system had both a publicly funded component for lower-income individuals and a private insurance system for those above the income threshold. This structure changed in 2006 when the Netherlands introduced a mandatory “basic insurance” for all Dutch citizens. Under the basic insurance scheme, private insurance companies are responsible for providing health care coverage and secure access to health care for their members. In addition, insurers cannot reject applicants and cannot impose a premium differential except on the basis of acquisition costs. To compensate for this, an elaborate risk equalization scheme is set up to compensate insurers who take on high-risk enrollees. The insurance companies are not required to pay corporate income tax for coverage provided on basic insurance plans, but the profits from those policies cannot be used to pay profits as dividends; rather, they can only be reinvested in the system—for instance, through premium reductions.

Insurers offer supplemental coverage in addition to basic insurance scheme. These plans are not as heavily regulated as the basic insurance. For instance, the rules on guaranteed issue, community rating, and risk equalization are not applicable, and profits may be paid out to shareholders. In 2016, approximately 84 percent of insured persons had some type of additional coverage (down from 88 percent in 2012). The primary service covered by these supplemental plans is dental care.

The basic insurance scheme is subject to regular changes in either the scope of coverage or the risk equalization methodology, but the basic characteristics have remained the same since 2006. Forty-five percent of the cost of basic insurance comes from nominal premiums paid directly to insurers by every citizen over 18 years combined with their own retention, applied as a stop-loss coverage for each insured person over 18 years. Fifty percent is funded through income-dependent employer taxes (also taxed as income for the employee), and the remaining 5 percent comes from general taxes. For citizens with low income levels, or those below 18 years of age, compensation is offered by the government to help cover the nominal premiums.

Eighty-eight percent of the Dutch health insurance market is divided between four large insurance groups, with market shares equal to around 30, 24, 21, and 13 percent. Individuals are given the option to change their insurance carrier once per year. The total annual cost (basic and additional insurance) per insured person (all citizens) has risen 12 percent from 2,707 euro in 2011 to 3,028 euro in 2016. Premium levels, however, have not increased; average annual premiums were 1,226 euro in 2012 and have decreased to 1,199 euro as of 2016. This is due to the fact that insurer profits in earlier years have been used to lower premium levels in later years.

All health care providers in the Netherlands are also private parties. Their salaries are mainly determined by regular collective employment agreements but are also subject to government-set salary caps for management.

The Dutch health care system is a highly regulated and very sophisticated system with private organizations at its basis. While health care costs are relatively high and still rising, the Netherlands is often ranked as having one of the best health care systems in the world on the basis of quality and accessibility.[8]

Lessons for the United States

The NHS in the UK is an example of a true single-payer health system. To keep the national health budget in control, the NHS must strive to keep it costs low. Rather than using high out-of-pocket costs as a mechanism to reduce utilization, as the United States does, the NHS instead uses the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to makes decisions as to the medications, tests, and procedures the NHS will pay for.

While health care costs are relatively high and still rising, the Netherlands is often ranked as having one of the best health care systems in the world on the basis of quality and accessibility.

France offers universal coverage through a multi-payer model. While coverage for the young and unemployed are paid for by the government, employed worker or retirees receive coverage based on occupation, with the employer paying a portion of the costs. There is no longer a role for an “insurer” in this model, and instead France uses “sickness funds” to pay claims and pool risk. Instead of each sickness fund negotiating independently, the government negotiates on their behalf with doctors, hospitals, and drug companies.

The Netherlands model is even more similar to that of the United States, using private insurance companies and providers. As with the provisions under the Affordable Care Act, coverage is mandatory and employers and employees are expected to contribute to pay the premium. The key difference is that there is only one “basic insurance” plan being offered and all participants are rated together. Because insurance companies must accept every applicant, and all residents must purchase insurance, a robust risk adjustment mechanism is needed to ensure fairness and prevent selective marketing to low-risk individuals.

THE AUTHORS are members of the Academy’s Health Practice International Committee.

References

[1] Duncan Ian, Healthcare Risk Adjustment and Predictive Modeling 2nd ed. 2017, Winsted, Conn.: Actex Publications. [2] Nicholas Timmins, Never Again: the story of the Health & Social Care Act 2012. A study in coalition government, The Kings Fund and the Institute for Government, Editor. 2012: London. [3] Greer SL Jarman H and Azorsky A, A reorganisation you can see from space: The architecture of power in the new NHS. 2014, Center for Health and the Public Interest: Ann Arbor, Mich. [4] The NHS Belongs to the People; 2013, NHS. [5] 2014 data from the FFSA study; global health expenditure: 191.8 billion euro. [6] Fillon Law of 2015 states that health private collective agreement is mandatory (with a defined level of coverage). [7] Marktscan Zorgverzekeringsmarkt 2016, Nederlandse zorgautoriteit, September 2016 (Marketscan Healthcare 2016, Dutch health authority, September 2016) [8] Euro Consumer Health Index 2016 (http://www.healthpowerhouse.com/files/EHCI_2016/EHCI_2016_report.pdf)