By Joe Allbright, John Have, Walter Marsh, Susan Mateja

Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of articles from the Health Practice International Committee on ideas from foreign models of health care that may assist the United States in finding cost-effective ways to deliver high-quality health care in an equitable and sustainable way.

The countries of North America highlight how differently neighboring countries can approach the same challenge. Examples range from the truly single-payer Cuban model to the two-tier Canadian health system, the multi-payer models of Mexico and the United States, and the largely informal system in Haiti. Unlike our discussion of Europe, there is little coordination of care among North American countries. There are limited instances of “medical tourism” across North America—individuals seeking access to elective services at a lower cost, or willing to pay a premium for a higher level of care—but for the most part, each country operates in a vacuum.

Below we examine three of North America’s national health systems in greater detail.

The United States

While the United States may be a global leader in medical research,[1] health market innovations, and world-class care, it is perhaps as well-known for its high costs, administrative complexity, and inequality in outcomes.[2] Unlike many of the world’s large developed health systems—often created en bloc as a response to a major social or political change—the United States system has evolved incrementally throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. What emerged is a patchwork of new systems and old, layers of federal and state regulations, and a growing number of organizations all sharing a large financial stake in shaping the U.S. health care space.

At a high level, the United States can be said to have three formal health schemes: a private health insurance system for those of working age and means; public options for those over 65, disabled, or eligible for assistance; and an emerging hybrid public-private system for those of working age and lower income. The remainder of the U.S. population are “uninsured,” falling outside these three systems. Emergency care for these individuals cannot be denied if they are unable to pay, but without the benefit of health insurance, they run the risk of accruing significant medical debt. There are currently 29 million Americans—9 percent of the population—without insurance; this rate has decreased from its high of 16 percent owing to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010.[3]

The most notable feature of the United States health care system is its strong private insurance market. There are many competing insurers and health plans, offering various levels of access, coverage, and savings through negotiated provider discounts. Nearly half of Americans are enrolled in employer-sponsored insurance.[4] Starting as a way to compete for employees during a post-war wage freeze, employer-sponsored insurance has grown as a result of tax deductions, cultural norms, and rising out-of-pocket costs.[5] The ACA further formalizes the employer system by penalizing employers that do not offer affordable coverage to their full-time employees.

Because an employer determines the insurer network, plan benefits, and contribution levels, the coverage American workers and their dependents have varies widely based on the organization that employs them. There is a risk for confusion and disruption in coverage as individuals change careers or enter/exit the job market. The wide variation in plan provisions and network discounts creates a system in which patients and doctors alike don’t know the final cost of a service until the bill arrives. As the cost of health care grows, employers are faced with an increasing portion of their expenses going toward employee benefits. There is a burgeoning market around solutions to lower costs through consumer-driven plans, employee well-being programs, and alternative delivery models such as telehealth and urgent care.

In addition to this private system, the United States offers publicly funded health care programs for those over 65 (Medicare) or those who qualify for social assistance (Medicaid). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) acts in the role of an insurer, negotiating fee schedules with providers, establishing cost-sharing and premium levels, and paying claims. The Medicare program is actually a series of integrated plans. Part A and Part B cover hospital and medical services, respectively, and are administered by CMS. Part C was introduced to allow private insurers the ability to offer plans, provided they could do so more efficiently than CMS. Part D extended the standard Medicare benefits to cover prescription drugs. Finally, there is a regulated private market for supplemental (Medigap) coverage that can reduce member out-of-pocket costs in exchange for an additional premium. Medicare programs are funded through a combination of taxes, trust fund investments, and in some cases monthly member premiums. Both state and federal resources are used to fund and administer Medicaid. Medicaid benefits are more generous than Medicare, but eligibility criteria and program specifics vary by state. All programs are facing long-term budgetary concerns due to rising medical and prescription drug costs, a growing number of Americans aging into Medicare, and the recent expansion of Medicaid eligibility.

Click to enlarge

Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Americans without employer-sponsored insurance who did not qualify for public programs would need to seek individual insurance coverage. These policies are significantly more expensive than employer-group offerings and left many with insufficient or unaffordable coverage. The ACA sought to improve this situation through employer coverage mandates, public insurance marketplaces, regulation of insurer rating for individuals and small groups, and (to prevent adverse selection) a requirement for individuals to purchase coverage. Individual policies purchased through these exchanges are standardized and federally subsidized based on household income.

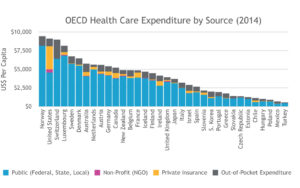

Each component of the U.S. health care system was introduced to expand coverage and improve outcomes, but the result of so many competing schemes has not always produced the desired results. For those with the means to navigate the system, the United States offers some of the most technologically advanced care in the world. For many, though, the ever-changing system of providers, carriers, sponsors, and plans is too complicated to use effectively. A lack of cost transparency inhibits the patient’s ability to select efficient care, and plan cost-sharing can obscure the true prices of services even after the fact. Costs are driven higher by new medical and pharmaceutical treatments, Americans’ rising rates of obesity and chronic disease, and the high cost of administration.[2] Despite having some of the highest levels of health care spending, the United States ranks in the bottom quartile among member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries on both average life expectancy and infant mortality. Some Americans are certainly aware of this state of affairs, and the conversation around health care reform—either toward more government involvement or less—has remained a much-debated social and political issue throughout the 21st century.

Canada

Canada’s national health insurance program provides coverage to all legal residents in Canada. Each of the 13 provinces and territories administers its own plan, with funding assistance from the federal government. To qualify for federal funds, plans must adhere to the following fundamental principles of the Canada Health Act:

- Comprehensiveness: Insurance must cover all medically necessary core hospital, physician, and diagnostic services, as well as in-hospital drugs and supplies. All core services are paid at 100 percent.

- Universality: All insured residents are entitled to the same level of health care.

- Accessibility: Insured residents must have reasonable access to health care facilities (with allowances for Canada’s remote locations).

- Portability: Insured residents should be allowed to move to another province—temporarily or permanently—without interruption of coverage.

- Public administration: The health insurance plans must be administered and operated on a nonprofit basis by a public authority.

Funding comes through provincial taxes and value-added or general income taxes, as well as some payroll taxes. Some provinces also have monthly premiums. The federal government subsidizes each province annually on a per capita basis. Separate federal government systems exist to cover active and veteran members of the Canadian Armed Forces as well as Aboriginal Canadians. In addition to its role as a payer, the federal government sponsors medical research and oversees the approval of new medical procedures and drugs. It also collects and analyzes detailed health care cost and utilization metrics from all the provinces, making the data readily available for research and analysis.

While insured services are offered to the patient at no cost, about 30 percent of health care expenses are not covered by the public plan.[6] This includes prescription drugs, dentistry, optometry, paramedical services, medical supplies, outside hospitals, and emergency medical services while outside Canada. These services can be paid for out of pocket or, more commonly, through a supplemental insurance policy. These private insurance policies may be purchased directly or through an employer.

Though hospitals in Canada are often publicly owned, physicians are mostly private and are reimbursed at a negotiated fee-for-service basis. Private clinics, providing publicly covered services at an additional patient cost, are not allowed under the Canada Health Act. Nonetheless, the idea of offering a “second tier” of coverage keeps resurfacing, largely as a response to criticism around wait times for elective procedures. The Supreme Court of Canada has been hearing a case that would allow doctors to set up private clinics and charge the cost back to an insurer or the patient for knee and hip replacements.[7] Such operations are currently only allowed in a hospital where services are covered by the provincial plan.

Like most countries, Canada faces some challenges in delivering health care. Prescription drug costs in Canada are second only to those in the United States. While the federal government regulates prescription drugs and establishes maximum prices for drugs sold under patent (when there are no generic substitutes available), the government does not currently negotiate drug prices or establish a national formulary as some other single-payer systems have.[8]

The current provincial plans were designed 40 years ago with focus on acute care, but now, as seniors age 65+ begin to outnumber children under 15, Canada has an increasing need to address issues around chronic illnesses. This includes a focus on quality care for those with chronic illnesses, such as palliative care and end-of-life services. Currently, there are many hospital beds occupied by seniors who may be better cared for at home or in seniors’ residences.

With health care expenses at 10.4 percent of GDP in 2015, about a percentage point above the average of OECD countries, Canada’s costs are still significantly lower than in the United States. Physicians and beds per capita is comparable to the United States, and the life expectancy of 82.2 years is the 12th highest in the world.

Click to enlarge

Mexico

The Mexican federal government instituted universal health care for all Mexican citizens in 2012, as guaranteed by Article 4 of the Constitution. The citizens are provided health care by the secretariat of health through the following systems (it is possible to have coverage through multiple programs):

IMSS: In 1943, the Instituto de Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) was created to provide health care coverage for employed individuals. This program is funded through a tripartite group made up of the public funding from the government, funds from the employer, and contributions based on salary from the employees. Approximately 57 million citizens (51 percent of the population) have coverage under this program.[9]

ISSSTE: In 1959, the Institute de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores (ISSSTE) was created to provide health care coverage for local, state, and federal government employees. The program is funded through the same tripartite group as the IMSS, with the government also acting as the employer. Approximately 12 million citizens (11 percent of the population) have coverage under this program.[9]

Seguro Popular: In 2003, the Systema de Proteccion Social en Salud (SPSS) or Seguro Popular was created to provide coverage to Mexicans who are not formally employed. This program covers self-employed, under-employed, unemployed, poor, and retired citizens. This program is funded jointly by the federal and state governments as well as through contributions based on the income of the individuals and families covered. Approximately 55 million citizens (49 percent of the population) have coverage under this program.[9]

Additionally, there are specific health care systems offered by the federal oil company (PEMEX), the armed forces (SEDENA), and the navy (SEMAR) for their members. State governments provide health services independent of those provided by the federal government, which are provided either free or subsidized by the states. There is also a private health care system available to those able to afford coverage. Private organizations operate under a free-market system to provide health care from private physicians at private offices, hospitals, and clinics. Less than 10 percent of the population is covered by private insurance plans, but many still choose to pay out of pocket to use the private hospitals.

Unlike an insurance-based scheme, each of the health care systems consists of its own health care delivery facilities (physicians, clinics, pharmacies, hospitals, etc.) with different standards of care. There is no portability; individuals are generally unable to utilize the facilities of another system. For one-third of individuals, a change in employment will result in a disruption in health care plan and physicians. This is especially difficult for those with chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart conditions, as they must change their primary care physician. The OECD has recommended that Mexico’s health systems expand their service agreements (convenios) to allow affiliates from one system to access the services of another system.[10]

Health outcomes in Mexico have been adversely affected by rising levels of obesity. From 2000 to 2012, the percentage of Mexican citizens who were obese or overweight increased from 62 percent to 71 percent. More than 15 percent of adults are diabetic (twice the OECD average of 6.9 percent). Over the past 10 years, programs have been implemented to improve nutrition, including food labeling regulations, a sugar tax, and restrictions on advertising to children.[11]

With the recent addition of the uninsured now being covered by public insurance, Mexico’s capacity to meet health care demand is strained. To help address this issue, Mexico has developed one of Latin America’s most sophisticated telehealth industries. Members are provided telephone access to licensed doctors 24 hours a day, seven days a week, along with deep discounts at a national network of more than 10,000 health care providers in clinics, labs, and hospitals. This service targets low- and middle-income households.[12]

Between 2003 and 2013, as an additional 50 million underinsured were brought into the Seguro Popular, public health care spending in Mexico increased from 2.4 percent to 3.2 percent of gross national product. There are both opportunities for savings (administrative load makes up 10 percent of health care costs) and compelling reasons to subsidize more (out-of-pocket expenses in Mexico are over 40 percent of total health spend, the highest in the OECD). The OECD has recommended that Mexico adopt measures to better harmonize the delivery systems, prices, health information systems, and administration across the multiple existing health schemes.

Lessons for the United States

Both Mexico and the United States face the same problems around portability, administration, and complexity resulting from fragmented health care systems based on an employer-sponsored model. In the United States, an individual changing jobs may also need to adjust to a new insurer and plan; in Mexico it could be an entirely new system of health care providers. Both countries exhibit some of the same administrative inefficiencies and delivery-side complexities that come with a hybrid multipayer model. Fifteen percent of health care costs in the United States go toward administration, compared with 10 percent in Mexico and 2 percent in Canada.

Canada offers the United States an example of a single-payer system that still provides a level of autonomy to provinces/states. While significantly smaller than the U.S. insurance market, supplemental insurance in Canada is still offered as a way for individuals to manage risk and for employers to differentiate themselves.

THE AUTHORS are members of the Academy’s Health Practice International Committee.

References

[1] “Though the U.S. Is Healthcare’s World Leader, Its Innovative Culture Is Threatened”; Forbes; May 23, 2012. [2] “The U.S. Health Care System: An International Perspective”; AFL-CIO Department for Professional Employees Fact Sheet; 2016. [3] “Early Release of Selected Estimates Based on Data From the 2016 National Health Interview Survey”; National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; May 2017. [4] “Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population”; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. [5] “The Real Reason the U.S. Has Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance”; The New York Times; Sept. 5, 2017. [6] National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2016; Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2016. [7] “Epic court battle over private health care rages in B.C. courts”; CBC News; Feb. 12, 2017. [8] “This is why Canada has the second-highest medication costs in the world”; National Post; Nov. 7, 2016. [9] Mexican Healthcare System Challenges and Opportunities; ManattJones Global Strategies; January 2015. [10] OECD Reviews of Health Systems: Mexico; Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development; 2016. [11] “Food-Related Advertising Targeting Children: A Proposal to Reduce Obesity in Mexico”; The Journal of Global Health; Nov. 1, 2012. [12] “Bridging the Health Care Gap Through Telehealth: The MedicallHome and ConsejoSano Models”; The Commonwealth Fund; Aug. 10, 2017.