By Jeff Reeves

Heart disease has been the leading cause of death in the United States for many decades, and remains so to this day. But while this category accounted for more than 635,000 total deaths in the latest data and 23.1% of all recorded causes,[1] the long-term story of heart disease is undeniably an encouraging one.

Thanks to progress in both treatment and prevention, there has been a steady and marked decline in the mortality rates from common conditions that include coronary heart disease and strokes. As a result, age-adjusted mortality rates for heart diseases declined by about one-third from the 1960s average to that of the 2000s.[2]

A host of related efforts deserve credit for this decline. From the innovation of high-tech surgical techniques to the distribution of maintenance medication to everyday efforts to stress diet and exercise, the fight against heart disease has been ambitious and comprehensive over these past few decades.

Now, public health officials and family physicians are being called on to answer a new and perhaps even more complicated challenge: so-called diseases of despair.

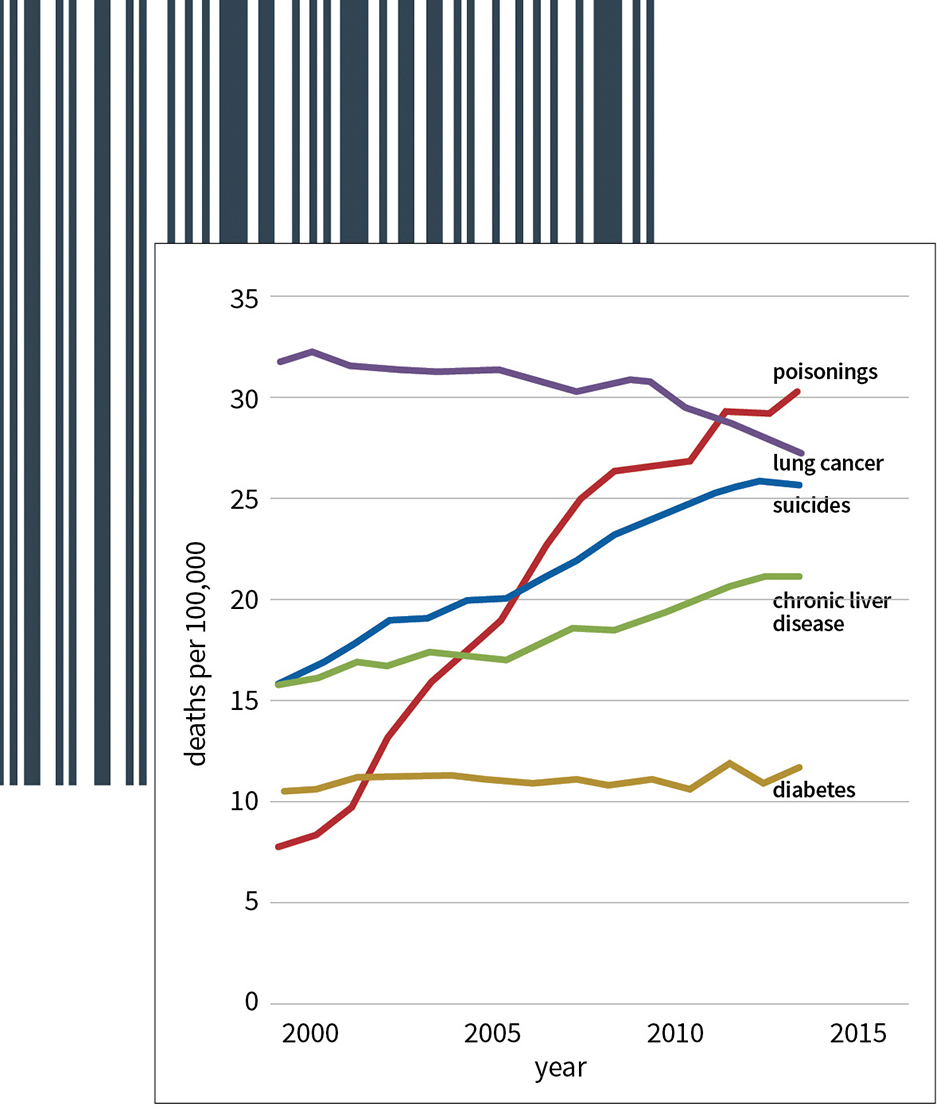

In 2015,[3] Princeton economists Ann Case and Angus Deaton coined this bleak phrase as they pointed to the three disturbing trends of rising drug abuse, alcoholism, and suicide—and a rapid rise[4] in deaths related to all three.

The raw numbers in these three mortality categories is admittedly much smaller than the number of deaths linked to leading causes, with 45,000 suicide deaths in 2016 vs. more than 635,000 for heart disease. However, the rapid growth rate in these categories makes them impossible to ignore.

In fact, a rapid rise in deaths linked to “diseases of despair” are the chief reason that the average U.S. life expectancy has declined in two of the past three years.

“Life expectancy gives us a snapshot of the nation’s overall health, and these sobering statistics are a wake-up call that we are losing too many Americans, too early and too often, to conditions that are preventable,” said Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control, in 2018.

This basic idea—that, unlike cancer or a car accident, these deaths are wholly preventable—is what makes these mortality trends so difficult to grapple with.

After all, the data shows that America is adept at unclogging arteries, avoiding blood clots, and reducing blood pressure.

Why is it, then, that so many Americans still suffer from broken hearts?

The Shape of Addiction and Suicide

Headlines about the declining U.S. life expectancy and the scourge of opioid addiction in the Midwest make for undoubtedly clicky headlines on social media. And alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicide are all highly emotional topics where personal experiences naturally color perception.

However, the data provide interesting insights as to the true shape of mortality trends.

Public sector actuaries charged with examining the underlying causes of suicide, alcoholism, and drug abuse have helped uncover key indicators and risk groups. And those in life and health insurance groups focused on risk management are also exploring ways to identify affected populations and estimate both current and future costs.

Here are some of the findings:

Drug Overdoses

Each day, more than 130 people die in the U.S. from opioid overdoses.[5] And while addiction generally is an illness that can happen to anyone—young or old, rich or poor—there are certain populations that are clearly more at-risk than others.

Specifically, a closer look at the data indicates that those most likely to suffer from addiction are older, white, and uneducated.

Age: Case and Deaton’s work highlighted a staggering finding that deaths from drug overdoses among people aged 45 through 64 surged 11fold in just 20 years from 1990 to 2010. By comparison, the 25-34 age group saw deaths rise less than half that rate.

Race: CDC data shows that of the 47,600 opioid-related deaths in 2017, 78% where to white, non-Hispanic Americans, though this group comprises just under 63% of the U.S. population. And overwhelmingly white West Virginia, where more than 93% of residents are white non-Hispanic, is the hardest-hit state in America, with an overdose death rate of 49.6 per 100,000 residents—more than three times the median figure of 15.5 death per 100,000 residents among all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Education: Lastly, data compiled by the Population Reference Bureau[6] shows overdose death of Americans without a high school diploma more than doubled from 14.0 per 100,000 in the period of 1992 to 1996 to 29.5 per 100,000 across the 2007-to-2011 period. While death rates for college-educated Americans also roughly doubled from a rate of 3.2 to 6.8 deaths per 100,000 in the respective periods, those without high school diplomas are still four times as likely to die from an overdose.

Alcoholism

Alcohol abuse similarly impacts families of all shapes and sizes, but is known to occur more often in certain segments of the population than others.

In general, most doctors see nothing wrong with a drink now and then. However, about one in six U.S. adults binge drink to excess according to the CDC, consuming eight drinks or more in a single session at least once a week.[7] That’s way beyond simply having a glass of wine with dinner or a beer at happy hour.

Here are the groups most affected:

Race: U.S. Census data shows American Indian and Alaska Natives are at highest risk, with an addiction rate of 14.9% for this group, followed by Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders with an 11.3% rate. Racial cohorts where alcoholism is least common are African Americans at a 7.4% rate and Asian Americans at 4.6%. However, a more in-depth analysis by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism found that while white Americans have a generally higher rate of alcohol consumption on the whole, liver diseases such as cirrhosis related to heavy drinking in fact occur at a higher rate for both blacks and Hispanics than for whites.[8]

Age: While alcohol consumption is generally common across age groups, young adults are at higher risk of health-related consequences from excess drinking. Americans ages 18–25 are at the highest risk of alcohol use disorder and unintentional injury caused by binge drinking that could lead to hospitalization or death, according to a recent demographic review.[9] A separate report by the National Institute on Drug Abuse[10] found that the age cohort 25 to 29 years old represented the highest percentage of admissions into alcohol treatment centers at 14.8%, followed close behind by the 20- to 24-year-old cohort at 14.4% of admissions.

Income: A 2010 study[11] on neighbor poverty rates looked beyond common “point in time” measures of economic distress to explore rates of alcoholism in fixed geographic areas over many years and how they related to personal income levels. It found that the rate of alcohol abuse waxes and wanes in kind with income trends—in other words, that roughly the same group of people in roughly the same town will drink more when they are poorer, and less when they are more financially secure.

Suicide

The issues of addiction and suicide are closely linked, with research showing that alcoholism is in fact a stronger clinical predictor of suicide than even a psychiatric diagnosis.[12] Thus it is unsurprising that the same communities suffering from drug and alcohol abuse also are at higher risk of suicide.

It’s also worth noting that suicide data, like mental health information, can be troublesome because of issues with under-reporting.

Age: According to the CDC, suicide is a particular problem for the very young and has risen to become the second leading cause of death among individuals between the ages of 10 and 34 behind only accidental injuries.[13] However, the rate per capita is most severe among those 65 and older at 31 suicides per 100,000—almost three times the average rate of 13.0 for the United States at large.

Gender: The suicide rate for American males is nearly four times higher on average than that of females.

Race: As with alcoholism, suicide rates among American Indians and Alaska Natives is significantly higher than nationwide norms at more than 22 deaths per 100,000 people. Non-Hispanic whites follow at a rate of nearly 18 deaths by suicide per 100,000.

Costs and Potential Solutions

Alcohol abuse, drug addiction, and suicide are all related problems that collectively exact a heavy toll on America. An analysis by public health nonprofits found that the total number of U.S. deaths in 2017 caused by alcohol, drugs, or suicide hit the highest since federal mortality data began being recorded in 1999—killing twice as many Americans as two decades prior.[14]

The human cost is real, both in regard to lives lost, but also in the context of the economic burden. A study of suicide in 2013 calculated the value of lost workplace productivity at $93.5 billion;[15] roughly $215.7 billion[16] was spent on drug overdoses alone from 2001 to 2017; using data from 2010, the CDC estimated excessive drinking costs $249 billion annually.[17]

Given the tremendous impact of drugs, alcohol, and suicide on American society, then, what is being done to address these problems?

Politicians have turned a bright light on the opioid epidemic in America, with the run-up to the 2020 presidential election featuring pledges of assistance on both sides of the aisle. At the same time, high-profile suicides in recent years including celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain and fashion icon Kate Spade have ensured suicide remains a key part of the national conversation.

But while awareness has grown in regards to these issues, tangible progress in the public policy arena has been harder to come by.

In 2018, a bill was signed into law that included telehealth provisions for addiction treatment as well as suspension of Medicare payments to drug dispensers who are under a credible investigation of prescription fraud.

However, these moves largely reinforce internal efforts already underway at insurers looking to adapt to the current landscape of American health care challenges—including the formation of the Alliance for Recovery-Centered Addiction Health Services, a partnership between public health nonprofits, major insurers like Anthem, and provider networks like the American Hospital Association focused on stopping substance abuse through early intervention.

And what about the nature of evolving risk pools for life or health insurers?

Defining ‘Fair’

On the surface, the challenge actuaries face regarding the evolution of health and life insurance underwriting is straightforward. Simply put, actuaries are bound by their strict professionalism standards of conduct, practice, and qualification, as well as the overriding legal requirements that must guide their work. However, the reality of health and life insurance in the age of Big Data uncovers some sticky philosophical issues that aren’t as cut and dry even when the letter of the law is clear—particularly with issues like drug addiction, where race and class are closely correlated to these serious problems.

“Insurance companies are in the business of discrimination,” in the blunt words of authors Ronen Avraham, Kyle D. Logue, and Daniel Schwarcz in a 2014 paper on insurance laws. “Insurers attempt to segregate insureds into separate risk pools based on the differences in their risk profiles, first, so that different premiums can be charged to the different groups based on their differing risks and, second, to incentivize risk reduction by insureds.”

Words like “discrimination” and “segregate” can evoke strong reactions. However, the authors argue that an emotional response to “fairness” concerns necessarily comes at the expense of efficiency and the proper pricing of risk.

“The efficiency costs of these laws stem principally from the fact that they attempt to force insurers to charge the same premiums to individuals who pose different predicted risks,” they write. “This can generate the twin insurance harms of moral hazard and adverse selection.”

Consider, for instance, a patient with a pre-existing medical condition that is a clear marker of higher future insurance costs. Under federal laws enacted first as part of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and later in the Affordable Care Act of 2010, the, insurers cannot consider pre-existing conditions in the underwriting process. However, the authors argue that prohibitions on “discrimination” against a patient with a pre-existing condition interferes with the natural process of risk reduction and the pursuit of an efficient structure for fair rates.

This legal prohibition on using pre-existing conditions to deny coverage surely applies to illnesses such as depression or addiction. However, the reality is that mental health issues are not as easy to identify as other conditions like hypertension or diabetes. That’s in large part because even after recent trends to bring conversations about mental health issues into the mainstream, many Americans still suffer alone.

Information from the Mental Illness Policy Institute notes that millions of Americans go undiagnosed or untreated for serious conditions that often go hand-in-hand with addiction and suicide. For instance, the group estimates[18] that more than 5 million Americans suffer from severe bipolar disorder—more than 2 percent of the adult U.S. population—but half of those individuals are untreated.

In the age of Big Data and intensive demographic analysis, then, it could be that some actuarial calculations are in fact a better marker of true risk than even self-reported patient data.

Just how much personal information can be used in those calculations, however, can vary greatly based on the type of policy or the state insurance markets.

As Avraham, Logue, and Schwarcz write in their 2014 paper on discrimination, there are few federal limitations outside of narrow use-cases such as the pre-existing conditions. The result is a patchwork set of local rules that can be confusing to navigate, and hardly seems aligned with the broad idea of

fostering some sort of fairness. They note that, at the time of their paper, “more than half [of state] jurisdictions do not ban the use of race in life, health, and disability insurance, twenty-three states do not ban its use in auto insurance, and seventeen do not ban its use for property/casualty insurance, which includes homeowners insurance.”

They note that the Affordable Care Act “preempted state law to articulate a principle that women should not be discriminated against even though they do indeed have higher medical costs, at least within certain age ranges,” but that such federal rule that pre-empts state authorities is a rarity.

In such an environment, where the use of some data is fair in one state but against regulations than others, there are obvious challenges to creating the balance between fairness and efficiency—or in truth, simply defining what you mean by “fairness” in the first place.

Those are big questions for academics, or for public policy experts who wish to debate the proper way forward, whether a federal statute, state regulation, or some combination of the two. But the duty of an actuary is actually “simple”: act honestly, with integrity and competence to fulfill the profession’s responsibility to the public and to uphold the reputation of the actuarial profession.

Still, the recent focus on the impact of suicide, alcoholism, and addiction has turned a bright light on these problems and the numbers behind them. That means public health actuaries may increasingly be called upon to assess the data, identify current trends, and help craft policies that will be part of the future solution.

References

[1] National Vital Statistics Reports; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; July 26, 2018. [2] “Decline in Cardiovascular Mortality: Possible Causes and Implications”; George A. Mensah et al; Jan. 20, 2017. [3] “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century”; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; Nov. 2, 2015. [4] “Opioid Overdose Crisis”; National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2019. [5] “Opioid Overdose Epidemic Hits Hardest for The Least Educated”; Population Reference Bureau; Jan. 10, 2018. [6] “Binge Drinking — United States, 2011”; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Nov. 22, 2013. [7] “The Epidemiology of Alcoholic Liver Disease.” National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2003. [8] “Alcohol Consumption in Demographic Subpopulations”; Alcohol Research. 2016. [9] “Drug Facts”; National Institute on Drug Abuse; March 2011. [10] “The Relationship Between Neighborhood Poverty and Alcohol Use: Estimation by Marginal Structural Models”; Epidemiology. Magdalena Cerdá et al. Jan. 21, 2014. [11] “Clinical predictors of eventual suicide: a 5- to 10-year prospective study of suicide attempters”; Journal of Affective Disorders. November 1989. [12] “Leading Causes of Death Reports, 1981 – 2017”; CDC.gov. [13] “Deaths From Drugs and Suicide Reach a Record in the U.S.”; New York Times; March 7, 2019. [14] “Suicide and Suicidal Attempts in the United States: Costs and Policy Implications”; Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior; June 2016 [15] “Economic Toll of Opioid Crisis in U.S. Exceeded $1 Trillion Since 2001”; Altarum. Feb. 13, 2018. [16] “The real cost of excessive alcohol use”; CDC.gov. [17] “About 50% of individuals with severe psychiatric disorders (3.5 million people) are receiving no treatment.” MentalIllnessPolicy.org.