By John Divine

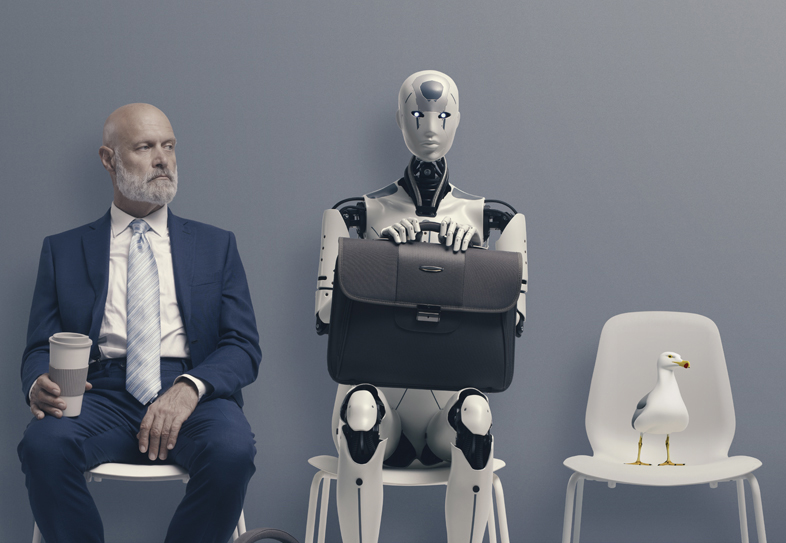

Far from an existential threat, this tech is seen as an avenue toward more strategic roles

There are moments in time when things previously thought impossible start to look eminently doable.

The prospect of artificial intelligence (AI) has been a compelling one since Alan Turing’s work in the 1930s and 1940s laid the groundwork for modern computer science. And since at least the 1960s, AI has captivated the imagination of the general public; Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey forced viewers to reckon with what intelligent machines might truly be capable of.

The technology itself continued to advance over the decades and went on to power some of the most ubiquitously used consumer technologies of the past 20 years. From Netflix’s recommendation engine to Google’s search results and Facebook’s News Feed, companies have used AI and machine learning to build companies that are collectively worth many trillions of dollars.

Of course, technologies that build companies can often displace jobs.

In 2020, this concern animated the Democratic primary campaign of Andrew Yang, who became the first presidential primary candidate of a major political party to reckon with widespread potential job losses at the hands of AI and automation. Yang saw this primarily as a threat to blue-collar workers like truck drivers who would be displaced by self-driving vehicles. Yang sought to implement a $1,000-a-month “Freedom Dividend”; this nationwide universal basic income (UBI) would offset, at least partially, the disruption caused by automation.

In the past year or so, this concern was flipped on its head with the late 2022 release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, a chatbot with an uncanny ability to answer questions, write speeches or scripts, and even do things like code and analyze data—all thanks to the power of large language models (LLMs).

While these LLMs are certainly fallible, the fact remains that it’s the white-collar workers who may be most imminently replaceable. Market researchers, graphic designers, customer service positions, and all manners of writers are just a few areas where AI could realistically pose a threat in the near future. The Writers Guild of America saw AI’s ascendancy as such a threat that limiting how AI could be used to write scripts was one of the core sticking points behind last year’s lengthy writers’ strike.

So, what does this have to do with actuaries?

Well, the recent technological progress in fields like AI and big data is translating directly into how actuaries perform their jobs, how employers plan to use actuaries, and even the problems that actuaries might be set upon to tackle.

Outsiders might naturally wonder: Is the actuary among the white-collar roles soon to be threatened by the relentless, exponential march of technological progress? Can’t some clever configuration of 0’s and 1’s replace the need for human actuaries? Isn’t there some anxiety around whether AI will make them redundant?

I interviewed nine actuaries for this article. Some are young, some more experienced, some sit in leadership positions at large companies or at the American Academy of Actuaries itself. And while there are other concerns to keep in mind, the actuaries I spoke with—almost universally—don’t see technology as a risk to the profession. On the contrary, actuaries see themselves as uniquely poised to thrive in the workplace of tomorrow.

The history of the actuary and how it has changed over time

While the role of the actuary—the professional pricer of risk—has remained fundamentally the same over time, the way actuarial work is conducted has not. Over the past century, two of the biggest changes to how actuaries work have arguably come from A) the emergence of universal professional standards, and B) increasingly advanced technological tools actuaries use to perform their jobs.

To the first point: While it may come off as self-serving to acknowledge in the Academy’s own magazine, facts are facts, and the creation of the Academy in 1965 was a watershed moment for the profession.

“Prior to the Academy’s founding in 1965, there were no standards that an actuary had to meet in order to practice in the United States,” writes former Academy President Tom Wildsmith in a 2017 paper called The Academy and the Web of Professionalism.

In establishing this so-called web of professionalism—which includes standards of practice, conduct, qualification, and a counseling and discipline board—actuaries and the work they produced were held to higher standards.

“The distinguishing mark of actuaries as professionals is that we recognize an ethical responsibility not just to our employers and clients, but to everyone who relies on the work we do,” Wildsmith writes.

As for technological changes, while the actuary of yesteryear was still concerned with quantifying risk, the way that was done evolved from pen and paper to calculators to spreadsheets, and continues to evolve in today’s brave new world of statistical modeling software, big data, and AI.

“What I really view AI and machine learning as doing is just (being) another tool in the toolbox for actuaries to use,” says Jonah von der Embse, corporate vice president and actuary at New York Life.

Von der Embse compares this new era of AI to “the advent of a calculator instead of using something like an abacus, or typing instead of writing something out on paper.”

These new developments, in turn, are changing how actuaries perform their work and what’s expected of them.

How tech is changing actuarial work

The way work is changing falls into a few different buckets.

The growing importance of communication and translation.

Yixuan Song is the value-based insurance design (VBID) model finance lead at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Innovation Center. He lays out how technological changes have resulted in shifting expectations for how he communicates his work to partners:

Back when I first became an actuary and worked at an insurance company, I was working in SQL and Excel—doing very technical things in applications that are more or less the bread-and-butter of what actuaries have been using for the past decade or so.

As the Society of Actuaries started imposing more predictive analytics requirements … I also saw that both myself and my peers started leveraging a lot more of these additional programs and softwares like R and Python into our workflows.

What’s been particularly challenging about that is while we’re able to more or less speak the same language as our data science colleagues and AI and machine learning engineers, we’re now seeing a larger and larger gap between our terminologies and the terminologies that our business partners are more familiar with.

With the gradual transition to R and Python, it’s a lot harder for them to look into the black box, and we frequently find ourselves having to—if we do anything with these fancier programs—having to translate that into Excel for their review.

Less rote work.

For this point, I found my conversation with Steven Armstrong, senior vice president and chief actuary for Allstate, to be illustrative.

Here’s an excerpt of our interview that gets into some concrete examples of how marketplace expectations for actuaries are already changing:

How are actuaries leveraging newer technologies now differently than they have in the past, and how do you see that changing going forward?

Allstate has a dedicated team working to advance automation within pricing analytics by reimagining our ratemaking and rate filing processes. This team has both actuaries and technology [professionals] working together to ensure automation brings rates to market accurately and efficiently. Automation improvements have already reduced actuaries’ time to create rate filings by 70% for several lines, with additional lines and more complex rate change types expected in the near future.

Actuaries at Allstate are trained in various programming languages and encouraged to produce work that can be leveraged by others. Automation within the pricing analytics is supported on all project types; it is part of the pricing culture at Allstate.

That’s a pretty dramatic reduction. I imagine with rate filings, a human must ultimately submit the rate filing, right?

Yeah, that’s exactly right. This does not take the human out completely.

What we want the artificial intelligence to do essentially is … every quarter this new data becomes available we want to have the artificial intelligence go into it, pull it out, and deliver a proposal that says, “in this particular state that you’re looking at, it’s saying that you should raise premiums by 10%.”

We won’t take that at face value. We must have an actuary come in and check for reasonability.

How long has that been the status quo?

So, it’s not our new status quo, but we’re building toward that. I would say we’re probably around 60% of our journey, and 2024 is going to be the year we turn the corner, and it should be ubiquitous, essentially, across all lines and all states where possible.

Is there a hope that new tech can take care of the rote, repetitive stuff and actuaries can be freed up to focus on other parts of the job? Is that already happening?

Yes, you know, we hire actuaries to do a lot of this rate-making work and actuaries can still be involved in that. I also need to think if I need actuaries to be the only people doing the drop-ins and the reasonability checks. It could potentially be done by somebody who isn’t necessarily an actuary. You might be able to delegate this to just really smart math people too.

I still do need, on the other side of that coin, my actuaries now to be doing very different complex problem-solving that transcends what they typically have done in the past,

So, it’s like you said, it frees them up.

More data science skills, to supplement actuarial judgment.

I asked Dorothy Andrews, a senior behavioral data scientist and actuary at the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, whether actuaries are expected to be more technologically proficient today than they were in the past.

Spoiler alert, they are:

Yes, we’re finding that actuaries are having to equip themselves with more data science-type skills … in particular to actually connect policyholder characteristics with loss outcomes.

And that’s different from the past because in the past pricing was really … there was a lot more actuarial judgment involved in pricing and underwriting. And people thought it was kind of fuzzy in many places because two actuaries could look at the same risk and get different classifications. It’s sometimes hard to track down why they picked an assumption that they picked.

But with algorithms, you have this tractable approach for developing your risk classification and your pricing result. So people like the fact that it feels like you can audit the results a lot better.

Concerns about new technologies

As fantastic as these novel tools can be, it’s important to keep in mind that, like almost anything in life, reaping the benefits comes with a trade-off. Here are some risks that actuaries need to keep in mind as they increasingly embrace technology:

Dependency.

“If we have something that streamlines our process and makes it so smooth and so fast, do we have people who lose the skills to be able to jump in and fix things when a fire happens or when something goes wrong?” wonders von der Embse.

“It’s critical that automating does not reduce our ability to learn those skills and be able to understand when things go wrong,” he says.

Todd Tauzer, senior vice president and national public sector retirement practice leader at Segal, agrees.

“Just how much do you depend on it compared to the more traditional things that [actuaries] depend on? And how much do you think it’s free from error?” Tauzer wonders.

Unintended negative social consequences.

One of the most pernicious potential downsides to new technologies, according to several actuaries I spoke with, lies with unintended negative social consequences.

Sherry Chan is chief strategy officer for Atidot and a former American Academy of Actuaries Board member. She says that in an era of big data, actuaries need to “make sure that we’re not using it in a discriminatory manner. Just because we don’t use someone’s race in the data doesn’t automatically allow us to say that it’s non-racially discriminatory, because there are proxies for race.

“We have to think outside the box a little bit and make sure that it’s not discriminatory and it is yielding accurate, truthful data.”

Von der Embse agrees, finding the ethical implications of algorithmic outputs, AI, and big data usage to be “the most critical [point] of all.”

“We need to be able to take a large-picture understanding of these model outputs and be able to say from an ethics standpoint if what it’s producing is right for everyone,” von der Embse warns, pointing to accelerated underwriting as one practice that could be potentially problematic.

“For accelerated underwriting, if you’re someone who is able to check a certain series of boxes, you won’t have to go through a full underwriting process,” von der Embse explains.

“If we’re creating systems that are able to underwrite people with a click of a button, it could speed things up,” he says, but “we want to make sure that we are first classifying risks in a fair and equitable and accurate manner. We also want to make sure that the people who are getting classified … that it’s fair … that it’s not only benefiting people who the model has been trained on for data purposes.”

I asked Andrews about her concerns with how technology is being leveraged by actuaries, and got an emphatic response:

My greatest concern is that actuaries are not really examining … the social underpinnings of the data and what kinds of social policies and practices may have embedded bias into the data that they’re using in their models.

I often say the algorithm is like the innocent bystander—it’s really just doing its minimization or maximization of some objective function. And whatever patterns exist in the data, the algorithm is likely to find and amplify them.

And so I’m worried that we aren’t doing enough on the front end to analyze what possible sources of bias may be embedded in the modeling data.

Because the modeling data plus the algorithm will produce algorithmic outcomes and you’ll see the biases in the algorithmic outcomes. That’s what concerns me. And I don’t believe actuaries are really trained to do that … unless you have a social science background, they’re not really trained to do that.

They’re basically taking the data blindly and fitting a model to it.

Data opacity.

Andrews acknowledges that, historically speaking, checking the societal impact and fairness of model outputs hasn’t really been in the actuary’s job description.

“Part of it is we didn’t use the kind of data that we’re using now with the advent of big data. You know, big data is not just about volume, right? It’s also about variety,” Andrews says.

This, she says, raises yet another issue:

A lot of that variety stems from the use of third-party data. And this is because we have gone from trying to understand who people are—from basic insurance application data, where they live, what’s their name, etc.—to how they behave. And you can’t necessarily understand someone’s behavior just by looking at their address.

The problem with a lot of this third-party data is it’s not auditable. Companies consider it proprietary. You either buy it or you don’t. And oftentimes the actuaries don’t understand anything about how that third-party data was constructed…

While insurance companies are feeling like they’re going to be responsible for any adverse results as a result of using third-party data, they don’t feel like they can ask the third parties to tell them what their secret sauce is.

So, this is a problem.

Overreliance, negative social repercussions and unauditable data—not to mention other issues like privacy concerns from public-facing AI software like ChatGPT—all make it sound like these newfangled tools might not be worth the stretch.

Of course, it’s not that straightforward. There are already real-world examples of major insurers no longer needing as many actuaries for certain types of fundamental actuarial tasks.

Take rate-making, for example. Remember what Allstate’s Armstrong said: “I have to think about how many actuaries I need to do that work. It should be a much smaller number than I’ve had historically because automation happens.”

While concerns about big data, AI, algorithms, and other new software exist, the incentive to streamline business and stay one step ahead of the competition is ever-present in any market economy. The adoption of new technology is more likely to speed up than slow down—especially if major industry players are already seeing concrete progress in automating actuarial work.

This might naturally raise the question:

Why are actuaries unconcerned about being replaced?

If actuaries should view recent technological leaps as a threat to their job security, they haven’t gotten the memo. Reasons behind their seeming nonchalance fall into several buckets:

It’s a tool.

Lisa Slotznick is a retired actuary and president of the American Academy of Actuaries. She had this to say about any perceived threat AI might pose to the profession:

One of the things that some of us older actuaries talk about that have been around a while: Think back to the days before spreadsheets existed. People were doing all the calculations by hand. And did having spreadsheets get rid of actuaries? No. It allowed us to do more things and to get into more aspects … that was one major leap forward for actuaries, and AI may end up being another major leap forward, but it’s not going to get rid of actuaries.

Professionalism.

While no one could have foreseen the explosion of AI and big data at the time, the core foundations of actuarial professionalism established in 1965 are still paying unforeseeable dividends almost 60 years later.

Song emphasizes that, while technology can present new challenges, actuaries are well-served to keep it simple and adhere to the standards as their North Star.

“I think we definitely have to be mindful of the ASOPs (actuarial standards of practice) and our Code of Professional Conduct when leveraging softwares that we might not have built ourselves,” Song says.

“Particularly as models get more complex and black boxes become even harder to interpret, there are resources out there that are developed by our data scientist colleagues that could help us in interpreting the results of these models and the potential biases in these algorithms.

“But we as actuaries just have to be cautious and recognize that ultimately if we’re signing any statements of actuarial opinion, we are responsible for being comfortable with the model,” Song says.

As an added bonus, the Academy’s web of professionalism also helps insulate the actuary from another perceived rival: the data scientist. While some see the gap between data scientists and actuaries as narrowing, here again professionalism comes into focus as a differentiator.

“Remember, the actuarial profession is cohesive in that we have a code of conduct, we have standards of practice, and we have a very large professionalism focus where we think about what we’re doing and the ethical implications,” Slotznick says.

“The data scientists—I’m not saying data scientists are unethical or data scientists don’t do it, but they might not rely so much on a profession-wide approach.

“If they work for corporate entities, all corporate entities have codes of conduct. So they have that, but they don’t have this with the possibility of discipline at the end. Yes, they can get sued, we can get sued, but we also have a disciplinary board within the actuarial profession,” Slotznick says.

Actuaries are flexible.

Even if you grant the assumption that AI will massively disrupt the employment needs of traditional employers of actuaries, there’s a sense that actuaries should still enjoy some reasonable degree of job security.

The business actuary “can solve presumably any business problem that requires data and analytics,” Armstrong says. “The business actuary should be able to lean in there and go, ‘Well, this isn’t a traditional actuarial problem, but because I have the skills and I understand the business I should be able to solve any number of these with access to the right data.’

“That’s why I see actuaries as typically employed and having a lot more longevity in companies.”

AI opens actuaries up to do new things.

Segal’s Tauzer is openly unconcerned about the risk of AI or machine learning threatening actuarial jobs. When asked if he had any anxiety about this, his response echoed the answers I got from most other actuaries across ages and industries:

Not for me. I don’t really have any anxiety.

I believe personally that actuaries have always been somewhat hindered by the sheer amount of work needed from the data and analytical perspective and the clunkiness of the work as the technology has been in its growing stages.

And so as AI and machine learning—or whatever the next step is in the process is—as that continues to grow and enhance our abilities in these areas … I think it will really unlock the ability of an actuary to become even more useful and critical to the organizations that utilize them.

So I’m honestly really looking forward to what can come next. I’m not really so scared of it.

Slotznick agrees that, if anything, AI can simply open more doors for the profession.

“The generative AI … it may make the work of an actuary less rote, for sure. And one of the things that we’re sure of is that actuaries will figure out how to harness it and make room in an actuary’s day-to-day for more analytical, more strategic thinking,” Slotznick says.

Some things are best left to humans.

Practically speaking, regulators are simply unlikely to allow certain things to be AI-generated.

“I don’t see a regulator accepting a rate filing that was generated by artificial intelligence, right? That’s just not going to happen,” says Vanessa Olson, senior vice president and chief actuary at Humana.

“So you’ll still need a human overseeing the process and documenting the inputs and the outputs and the conclusions and why those conclusions are reasonable. But the AI can help speed up the work, can help people explore other ideas, analyze data in different ways.

“So there’s a lot of potential advantage that comes from using the technology, but I don’t see that it’s ever going to replace us,” Olson says.

New horizons

Not only do actuaries see new technologies as a boon to their jobs rather than a threat, but many also expect more opportunities in different fields to emerge. The Bureau of Labor Statistics agrees, with the Labor Department projecting a 23% increase in the number of actuaries between 2022 and 2032—a growth rate far outpacing the average profession.

But … why? Where might all of this expected future demand come from? Slotznick has some ideas.

The demand will come from all of our different practice areas. The demand will also come in new and emerging areas that are related to existing practice areas. We see actuaries going into the world of climate disclosures and helping companies with those disclosures, they have to deal with air and climate, but more based on our analytical skills.

We see actuaries getting more involved on the asset side. There have always been actuaries involved in assets, but there’ll be even more going forward. And we see insurance being even more pervasive.

We see major insurers leaving certain states [due] to climatic type issues like the wildfires in California and the hurricanes in Florida … so actuaries are involved in all these things.

Armstrong, Allstate’s chief actuary, also highlighted climate as an area he expects actuaries to be more involved in in the future. He called out two additional areas of potential growth as well, starting with electric vehicles.

“They’re very, very different cars. They have different insurance needs. They require different products,” Armstrong says.

Separately, Armstrong sees the more general theme of transportation in America as a space with actuarial needs.

“I think autonomous vehicles are going to come back. And as technologies grow where cars can talk to other cars and talk to stoplights and things of that nature—which is kind of tied into the whole autonomous bit—that just changes the risk landscape in some unique ways that actuaries need to be prepared for,” Armstrong says.

Conclusion

The job of pricing risk has come a long way since the ’60s, when the profession decided it would like the actuary title to actually mean something, and that that meant nationwide standards would have to be put in place.

Since then, the biggest changes to the job itself have mostly come from technology, which remains the most likely culprit for driving change in the profession going forward (with a little help from phenomena like climate change, which might also be said to result from technology, but I digress…).

Actuaries aren’t shy about the numerous challenges posed by new technology in their work: understanding the inputs and how it works; not blindly accepting its outputs; avoiding overreliance; vigilantly patrolling any negative social consequences; privacy concerns—each of these requires the actuary to be conscious of such pitfalls and act proactively to address them.

At the same time, the very fact that actuaries are already mindful of these issues is encouraging. And actuaries clearly see technology, warts and all, as a boon to their profession—something that will open them up for higher-level, more strategic work, and even entirely new lines of work in industries that have yet to truly take off.

While Andrew Yang’s concern that automation would soon force millions of truckers out of a job hasn’t played out yet, that future is perhaps a little less hard to imagine than it was back in 2020. For actuaries, however—in part because of their ability to embrace and utilize new technology—the future looks bright.

JOHN DIVINE is a writer based in Charlotte, N.C.

Vanessa Olson, senior vice president and chief actuary at Humana

Why do you see companies wanting to employ actuaries vs. other professions—what do they bring to the table in terms of skill sets?

I think companies will still want to hire those classically trained actuaries—the ones who go through the examination process and get their credentials.

Because their training and their experience gives them the ability to understand and explain and model the financial dynamics of their businesses. And also because of the high professional standards to which they are held accountable. I think that’s a really important piece of why actuaries are so valuable to the companies that they work for: There’s a very high professional standard that they are held to.

And that may differentiate them from some of their other analytical counterparts.

Sherry Chan, chief strategy officer for Atidot and former Board member, American Academy of Actuaries

Is there a hope that new tech can take care of the rote, repetitive stuff and actuaries can be freed up to focus on other parts of the job? Is that already happening?

There are some who fear technology, fear the development of AI (and especially generative AI), or things that could alter our current environment and operations. But I actually see it as an opportunity. Just as with any SWOT [strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats] analysis, for every threat there’s an opportunity.

The way I see it is it’s not that it replaces the actuarial work. It frees us up to do more strategic work, like advanced storytelling, thought processes, and deliverables.

The opportunity is for actuaries to take on a more strategic role and take the results from these complex models and weave the trees together to tell the story of the forest to their clients. Actuaries can interpret the data that comes out and add that human aspect to it and ask questions like ‘What do you do with this data now?’ When we have all this rich insight, we can advance our work and not just be the back-office spreadsheet-builders.

Why do you see companies wanting to employ actuaries vs. other professions—what do they bring to the table in terms of skill sets? What sets them apart?

In actuarial science, we have not only a professional code of conduct, but also a board that disciplines actuaries who do not abide by it, which sets up apart from others.

Because of this setup, employers can have confidence in the work actuaries do because their credentials are tied to the high-quality level of their work.

Also, through our journey of the actuarial exams and getting credentialed, we acquire a wide breadth of knowledge, from accounting to economics to investments to obviously actuarial science and statistics. This provides a very holistic view, which further differentiates us from other professions.

Tell me about how your company uses next-gen tools to drive business decisions.

My company is in AI predictive analytics within the insurtech space. We use AI to help the life insurance ecosystem understand policyholder behavior better. It’s important to know various perspectives when predicting someone’s behavior.

We have three sources of data: data from our own clients, data from our partners in the industry, and public data. In aggregate we have access to about 40 million insurance policies from which we gauge customer behavior.

For example, we look into whether one has a vacation home. If they do, they may be more likely to buy a certain type of life insurance policy.

You may think, ‘What does a second home have to do with anything?’ But our models do show a high correlation. ZIP codes also unpack an extensive amount of information, from the average number of kids to churches versus bars per capita.

All these data points are very much related and with this type of data and our proprietary models, we’re able to predict things like whether a policyholder is going to lapse within the next four months.

Yixuan Song, VBID model finance lead at the CMS Innovation Center

What do you see as actuaries’ competitive advantage in the job market?

I think part of what we have that we don’t see for data scientists or other similar professions is our code of conduct, … our ASOPs, and the ABCD [Actuarial Board for Counseling and Discipline].

We have that as a backstop for any improper use of our profession’s credentials.

And we really don’t see that to such an extent for other similar professions. I think that gives us more credibility and ability to police ourselves as a profession compared to similar groups.

Is there any sense or fear among the profession that AI or machine learning will threaten actuarial jobs anytime soon?

To the extent that there are other professions that could easily replace us, I’m thinking of roles that are largely repetitive—things that you have to do year over year or month over month.

But when we think about bigger-picture issues or broader decisions that really do rely on a judgment that is not easily captured by the current AI machine learning landscape … I don’t hear as much grumbling or concerns about a replacement for our profession.