The Title of ‘Actuary’ Over 20 Centuries

In Memory of David Charles Heavilin (1946–2012), Actuary and Friend

By Ken Faig, Jr.

Julius Caesar required that the Roman Senate post its acts or proceedings in 59 BCE (see Smith). It is debated whether the original actuarii were the speedy note takers or the officials responsible for the compilation of the acts. Some would relegate the former duty to shorthand-using scribes or notarii. But it should be noted that the Oxford Latin Dictionary defines actuaria as a fast passenger vessel with both oars and sails.

During the classical period, Seneca [letter to Lucilius iv.xxxiii.iv.9], Suetonius [Divus Julius 55.3], and Petronius [Satyricon 53.1] all made reference to the actuarius. Some scholars like Robert Leslie Dunbabin (1869–1949) have maintained that the original title was “actarius,” from the “acta” or acts of the Senate. However, actus (meaning an act, deed or driving) with ablative form actu has also been suggested as a source.

Nettleship (30) wrote:

Velius Longus, p. 74[1], says that a distinction was drawn between actarius and actuarius: actarius being scriptor actorum, actuarius qui actum agit or (p. 155) qui diuersis actibus occupatur.

Dunbabin believed that second-century grammarian Velius Longus was correct in distinguishing the two offices. Whatever the lexicographical issues involved, the form actuarius was the one that prevailed.

The Senate lost much of its power and prestige under the emperors beginning with Augustus. It continued after the deposition of the last Roman emperor in the West in 476 CE, and held its last recorded session (apart from ephemeral later revivals) in 603 CE. (Its meeting place, the Curia Julia, was converted to a church by 630 CE.) In the East, there is record of the Senate continuing through the 14th century. Just how long the Senatorial office of actuarius persisted is unclear.

But a revival of the title actuarius was not long in coming. This time it had a military origin. Beginning in as early as 123 BCE (under the title frumentatio), the annona was the grain dole provided to the citizens of Rome from producing regions around the empire. The Roman army also received much of its pay in kind of which grain for baking was an important component. The annona militaris for the distribution of pay and supplies to the military was instituted during the second century CE. The civilian official charged with the administration of the annona militaris was titled the actuarius. The functions of the office apparently included accounting for and auditing of the program.

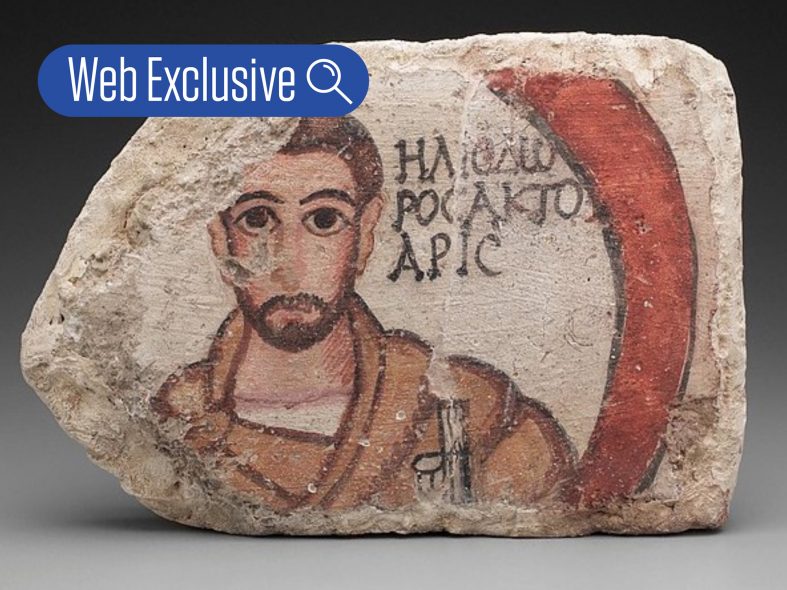

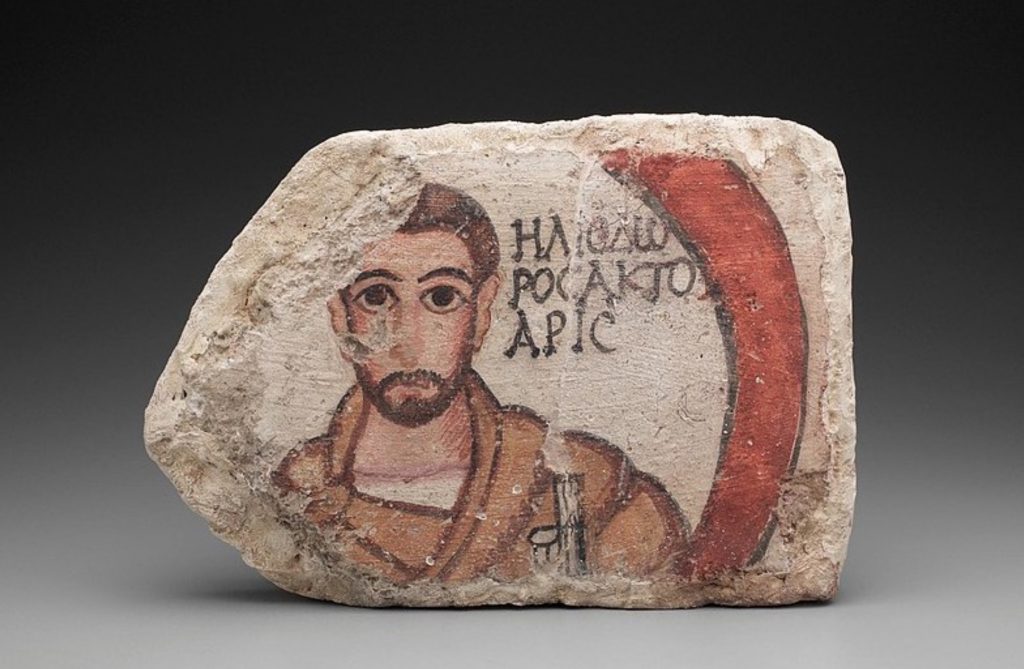

We even have a Roman ceiling tile excavated in 1928–37 by Yale University archaeologists at Dura-Europos, Syria (block L7 A31, House of the Scribes) which depicts an actuarius who bore the name Heliodoros:

The tile is dated to the first half of the third century CE. The British Library holds a letter from the actuarius Agathus, who was being detained in Arsinoe. He asked that a certain Uranus be kept at Dionysias until his return so that he might check the accounts for the collection of the annona. Regulations of the dux regarding the annona quotas collected were then provided. Agathus directed that the wheat collected should be kept under lock and key in the camp and that a quality inspection should be done. This cursive script letter on papyrus dates from the reign of emperor Constantius II (337–361 CE).

By the end of the fourth century CE, the office of actuarius had come into disrepute on account of the corruption of the office holders. Dill (228-229) wrote of the downfall of the office:

The accountants of the army stores (numerarii, actuarii) were audacious offenders. They are plainly charged with falsifying accounts and drawing larger supplies than the corps were entitled to. The actuarii seem to have been a particularly troublesome class, and are ordered away from the capital by a law of Arcadius in 398.[2] But it was at the hands of the various officials charged with the duty of enforcing payment and collecting arrears that the provincials suffered the worst cruelties. There was apparently no possible means of restraining them. Their insolence is described most vividly and punished most fiercely in some of the latest laws in the Code.[3] By demanding receipts which had been lost,[4] by over-exaction,[5] by fraudulent meddling with the lists of the census,[6] by mere terrorism and brute force, they caused such misery and discontent that the Emperor[7] had more than once, at all costs to the revenue, to order their removal from a whole province. Their exactions and super-exactions had reached such a point in 440[8] that Theodosius and Valentinian issued a rescript which gave the governors of provinces the power of punishing them without any fear of the Counts of the treasury. But the effect on the collection of the revenue, and, not least, the slur on the “illustrious” officers, whose powers were thus curtailed,[9] or whose gains were diminished, compelled the Emperor two years afterwards to rescind the former law. It is only too evident that the Emperor’s zeal for honest administration met with deadening opposition in the highest as well as the lowest ranks of the service. The “defensores”[10] of cities had, as one of their most important duties, to protect the taxpayers from over-exaction. Yet one can see, from a law of 409,[11] that the protection was often not to be relied upon. The defrauded provincial is directed, in the first instance, to appeal to the defensor, the curia, and the magistrates. If they refuse to accept his appeal, he is, as a last resort, in the presence, and with the cognizance, of the public clerks and minor officials, to post up his complaint in the more public places of the municipality. There surely never was a more startling confession made by the heads of a great administrative system.

In the West, the barbarian armies commanded by Odoacer and Theodoric replaced the Roman army. Just how long the actuarii may have persisted in the Roman army of the Eastern empire I have not been able to ascertain, but in any case the office must have become extinct after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. In the Eastern empire in the 10th century, the title aktourarios was granted to the official who handed awards to victorious charioteers. Later, the title was used for physicians attached to the imperial court.

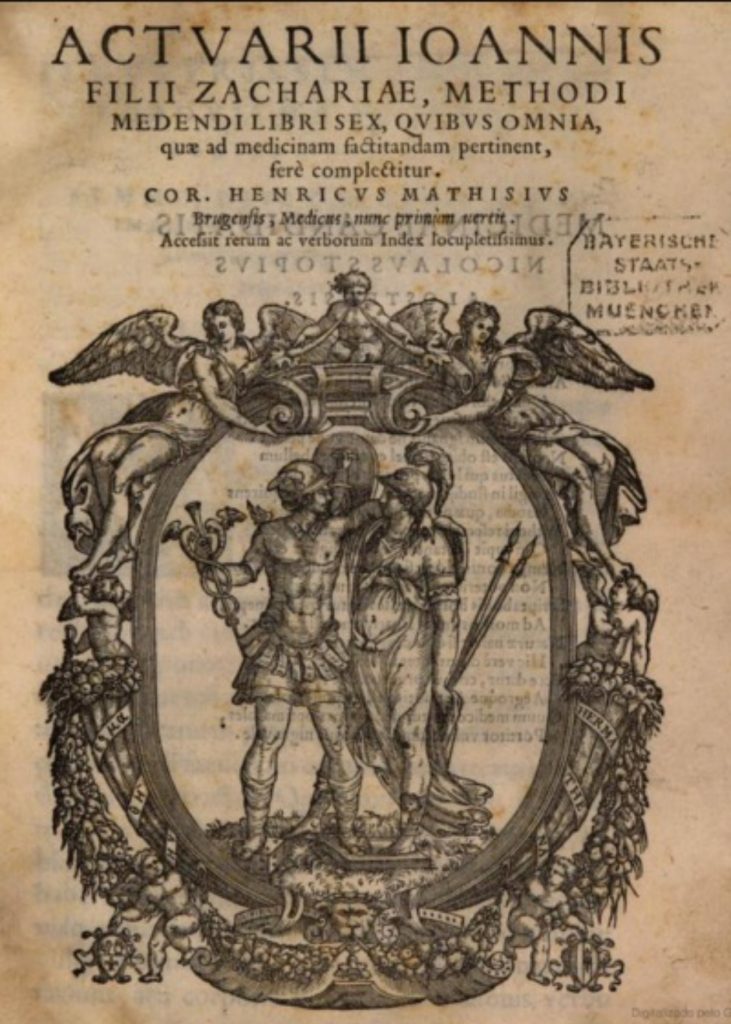

Latin translation of work by Byzantine physician Joannes Zacharias (c. 1275–c. 1328), who bore the title actuarius.

Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman empire under the emperor Constantine in A.D. 323. While it distinguished itself from the erstwhile Roman cults (which were mostly defunct by the end of the fourth century), Christianity in the West also adopted the Latin language of the empire for its liturgies and many of the forms and customs of Roman civilization.

As the Catholic Encyclopedia attests, by the dawn of the second millennium CE the office of actuarius was even seeing a revival in the church’s developing ecclesiastical courts:

Notary (actuarius), whose presence was decreed by Innocent III in the Fourth Lateran Council [cap. 38, c. 11 de probat., X. II(19)] is a public person whose obligation it is to transcribe with fidelity the acts of the case. As this office is merely that of a clerk, and does not include any judicial power or jurisdiction, it may be held in ecclesiastical courts even by a layman. Still, clerics are not excluded from this office, nor does cap. 8 , “Ne clerici vel monachii,” etc. X. (III(50)) contradict this, as there it is a question only of clerics who hold such office for the sake of pecuniary profit; nor is the contrary affirmation of Fagnani of any weight, as it is not supported by conclusive reasons. This is shown also by the actual practice of ecclesiastical courts. It is sufficient here to call to mind the notaries of ancient times who wrote down the acts of the martyrs, those who were employed in the councils, and still more the class of the prothonotaries, who have recently been divided by Pius X (21 Feb. 1905) into four classes, and rank among the highest prelates.

The title actuarius has persisted in the Roman Catholic Church. In 1907, in the Diocese of Pittsburgh, the curia pro causis disciplinaribus had Rev. William McMullen as its actuarius and Rev. J. Greaney as its assist. actuarius. Msgr. Camille Perl (1938-2018), former secretary of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei, was also a holder of the title. In the Chicago Archdiocese, the auditor of the Office of Canonical Affairs has also borne the title actuarius. In the June 23, 2022, news release announcing his promotion to chancellor effective July 1, 2022, Deacon David Kane explained his former duties:

In his current role as auditor-actuarius, Keene works within the Office of Canonical Affairs to prepare documents and petitions on behalf of the archbishop for priests and deacons returning to the lay state. In addition, he assists the Vicar for Canonical Affairs and the chancellor in assembling documents and researching applicable canon law for special cases.

Today’s actuarius in the Roman Catholic Church is hardly a mere note taker even in the sense of a recorder of official acts. He often appears be concerned especially with the nexus of civil and canon law. I have not been able to determine the number of current holders of the title actuarius, which I presume is granted by the Roman curia upon petition by or on behalf of the local ordinary.

In England, the Church of England succeeded the Roman Catholic Church under Henry VIII in 1534. The General Synod of the Church of England (with its three houses of bishops, clergy, and laity) came into being in 1970, replacing the earlier Church Assembly. Ogborn-2 (234) writes of the role of the actuarius in the ecclesiastical courts of the Church of England:

The first definition [court clerk] is supported by four examples from 1553, 1658, 1667 and 1717. [Young 482 details these examples.] The Court of Arches had an official called an Actuary (now the Registrar) whose duty was to attend the Court and set down the judges’ decrees. The Lower House of Convocation had and still has an official called an Actuary who registers the Acts and Constitutions of the convocation. In this usage the title of actuary derives directly from the Latin actuarius. It can scarcely be maintained that this meaning is obsolete, although its sound may have an archaic ring in the ears of the professional actuary.

Although many of their erstwhile functions have since 1970 been absorbed by the General Synod, the Houses of Convocation of the provinces of Canterbury and York still exist and meet from time to time. For each province, the bishops belong to an upper house and the clergy to a lower house. The deputy chair of each house is known as the prolocutor or spokesperson. The Court of Arches is a still-extant appeals tribunal for the province of Canterbury.

In other Protestant churches (e.g., those of Holland and South Africa) the office of actuarius is generally held by a canon lawyer. The Dictionary of South African English quotes an 1843 statute as follows:

An actuarius synodi shall be appointed from amongst the ministers, the actuarius being charged—(a) with transcribing during the sitting of the general church assembly, (b) with conducting the correspondence, (c) with the care of the synodal papers and books, besides the synodical repertory, (d) with framing and continuing a systematical registry in an alphabetic form of the acta synodi.

As early as 1831, Rev. A. Faure held the title actuarius and quaestor in the Synod of the Reformed Church. In 1866, the synodical Commission consisted of the moderator, the scribe, the actuarius, five acting ministers, and three elders (or retired elders nominated by the Synod). Rev. David Botha of Belville served as actuarius or registrar in 1974.

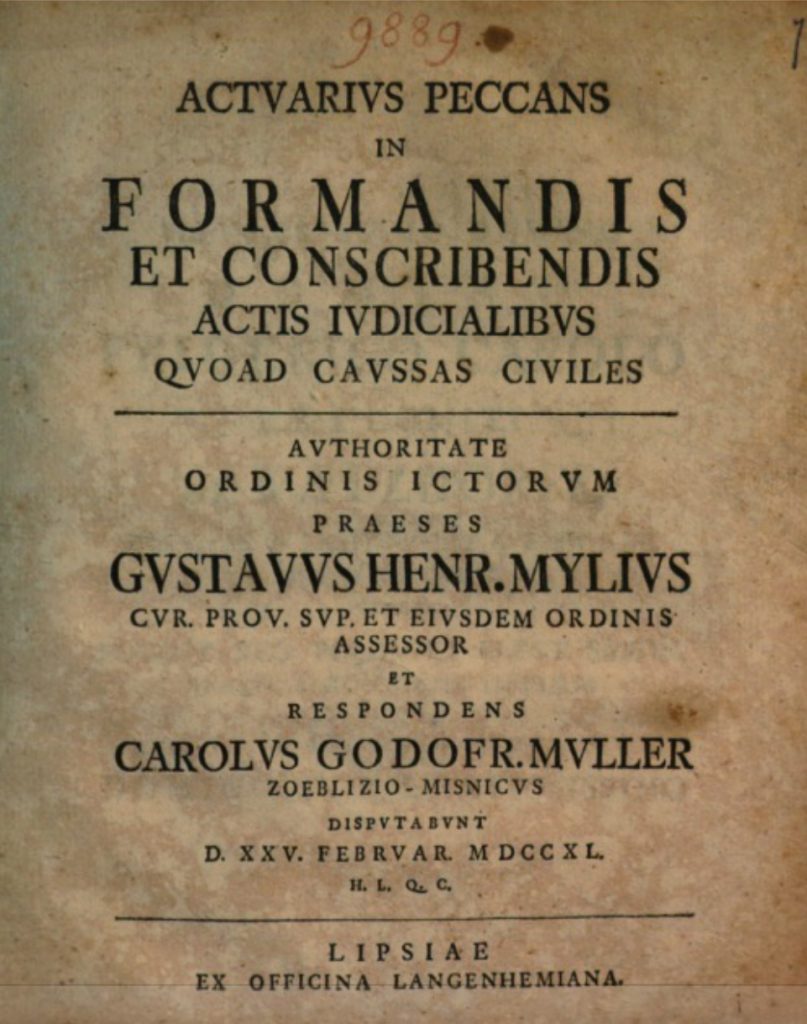

In the 18th century, the title actuarius also still existed in the civil courts in some jurisdictions. The Leipzig jurist Gustav Heinrich Mylius (1684-1765) published between 1737 and 1754 a number of legal disputations sharing the common title Actuarius Peccans[12] of which many are available on Google Books and of which the following is an example:

The first insurance company official to use the title actuary for insurance mathematicians was Edward Rowe Mores, M.A., F.S.A. (1730–1778).[13] His “F.S.A.” stands for Fellow, Society of Antiquaries (not Actuaries), to which he was elected in 1752. He was the son of Edward Mores (1681–1740), rector of Tunstall, Kent, for nearly 30 years, and his wife Sarah Windsor (born 1700), who married in Greenwich, Kent, on March 25, 1728. (Sarah married (2) Richard Bridgman, father of her son’s later wife.) According to Ogborn-2 (235), Mores was a graduate of the Merchant Taylors School and Queen’s College, Oxford (matriculated 1746; B.A., May 12, 1750; M.A., Jan. 15, 1753). Whether he ever took holy orders is undecided; for a time, he pretended to the title D.D. (Sorbonne) and affected the academical dress of a Dominican friar. He married in 1753 Susannah Bridgman (1730–1767), the daughter of Whitechapel grocer Richard Bridgman and his wife Susannah Edwards. Edward and Susannah had a daughter Sarah Ann (born May 9, 1754) [married July 18, 1774 John Davis, house decorator of Walthamstow] and a son Edward Jr. (born Feb. 9, 1757, died Apr. 15, 1846[14]) [married (1) Jan. 14, 1779 Mary Spence (daughter of James Spence and Mary Drew) and (2) Mar. 8, 1795 Sarah Rowe].[15] His daughter Sarah Ann (Mores) Davis may have been among the world’s final native Latin speakers, since her father customarily conversed with her primarily in that language from her infancy onward. She was sent to a convent in Rouen for further training, and there converted to Romanism, arousing her father’s anger. She died young, while her father was still living.

Mores’ wide interests included not only antiquities but also heraldry. He was also interested in typography and wrote A Dissertation Upon English Typographical Founders (1778). From 1756 onward, he lived mostly on the income of an estate at [Low] Leyton in Essex left to him by his father, where he built a whimsical house that he called Etloe House. It was later the country residence of Cardinal Wiseman, a convent, St. Pelagia’s Magdalen Home (closed 1920s) and the Home for Roman Catholic Feeble-Minded Girls (closed 1970s). George Goodwin recorded of Mores: “Towards the close of his life Mores fell into negligent and dissipated habits.” When he died, he was buried beside his wife in Walthamstow churchyard. Few modern actuaries would probably find much to identify with in the eccentric polymath Edward Rowe Mores, but his efforts toward the founding of the Equitable Society and his use of the title Actuary for its mathematicians nevertheless mark him as an important figure in the evolution of the actuarial profession. His knowledge of antiquities, including the use of the title actuarius in civil and ecclesiastical tribunals, doubtless influenced his advocacy of the title ”actuary.”

Edward Rowe Mores, engraving by James Mynde[16] after portrait by Richard van Bleeck. National Portrait Gallery.

Etloe House, 180 Church Road, Leyton, Essex.

The duties which Mores outlined for the actuary of the Equitable Society (Ogborn-2 236) seem to have related primarily to record-keeping as opposed to risk selection, pricing or valuation. Richard Price, D.D., F.R.S. (1723–1791) provided actuarial advice to the Society from 1768 until his death. William Morgan, F.R.S. (1750–1833), elected Actuary of the Society in 1775, was the first holder of that title to perform functions conforming to those of the modern actuary.

William Morgan painted by Thomas Lawrence. Institute of Actuaries, Staple Inn Hall.

The period 1800–25 was probably the critical period for the adoption of the title “actuary” by insurance company mathematicians. The term “actuary” was first mentioned in legislation in the Friendly Societies’ Act of 1819. Among the opponents of the new terminology was William Morgan himself. Mitchell (3) wrote:

Morgan disliked the title. He considered it an “affected appellation,” and at the time he acquired it, that was probably a fair description. But Morgan’s scientific and managerial ability as actuary turned a somewhat peculiar synonym for managing secretary into a prized professional designation.

The triumph of the new terminology was complete by the time the Institute of Actuaries was founded in 1848. The Institute obtained a royal charter in 1884 and merged with Scotland’s Faculty of Actuaries in 2010. The Society of Actuaries in the United States resulted from the merger of prior bodies (1889, 1909) in 1949.

Some might maintain that the early third-century Roman jurist Ulpian (ca. 170-228?) was a more significant precursor of our modern actuarial profession than the military accountants or later civil and ecclesiastical tribunal officials who bore the title actuarius. The eccentric antiquary Edward Rowe Mores was the originator of the term actuary as applied to our modern profession. Two centuries of his successors have borne the title with honor. Instead of dying out between the actuarii of the Roman Senate and the modern actuarial profession, the title “actuarius” maintained a presence over the intervening centuries. The antiquarian Edward Rowe Mores chose it for the mathematician of the Equitable Society, and by 1848 actuary had become the standard title for the modern profession.

References

Dill, Samuel, M.A. (1844-1924), Roman Society in the Last Century of the Western Empire, London: Macmillan, 1898.

“Edward Rowe Mores,” McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia. Available at: https://www.biblicalcyclopedia.com/M/mores-edward-rowe.html.

Goodwin, George (1856-1915), “Edward Rowe Mores,” Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, vol. 39. Available at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Mores,_Edward_Rowe.

Mitchell, Robert B[aird] (1903-1994), From Actuarius to Actuary: The Growth of a Dynamic Profession in Canada and the United States, Chicago, Illinois: Society of Actuaries, 1974. Extracts available at: https://www.soa.org/49347f/globalassets/assets/files/edu/edu-2012-c2-1.pdf.

[Mores-1]. Mores, Edward Rowe, A Dissertation Upon English Typographical Founders and Founderies With An Appendix by John Nichols, &c. &c. , New York: The Grolier Club, 1924. Edited by D[aniel] B[erkeley] Updike (1860-1941). Contains Richard Gough (1735-1809), “Memoirs of Edward Rowe Mores, D.D., F.S.A.,” pp. ix-xviii. (Original edition, 1778.) Grolier Club edition (1924) available at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Dissertation_Upon_English_Typographica/c_m6AAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Mores,+Edward+Rowe&printsec=frontcover. [Mores-2]. Mores, Edward Rowe, A Dissertation Upon English Typographical founders and Founderies (1778) With a Catalogue and Specimen of the Typefoundry of John James (1782), London: Oxford University Press, 1961 (second printing, with corrections, 1963). Edited by Harry [Graham] Carter (1901-1982) and [Sir] Christopher [Bruce] Ricks (born 1933).Nettleship, Henry, M.A. (1839-1893), Contributions to Latin Lexicography, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1889. Available at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Contributions_to_Latin_Lexicography/_4oNAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover.

[Ogborn-1]. Ogborn, M[aurice] E[dward] (1907-2003), “The Actuary in the Eighteenth Century,” Proceedings of the Institute of Actuaries Centenary Assembly, Cambridge University Press, 1950, vol. 3, pp. 357-386. [Ogborn-2]. Ogborn, M[aurice] E[dward], F.I.A., “The Professional Name of Actuary,” Journal of the Institute of Actuaries (vol. 82 no. 2, 1956), pp. 233-246. Available at: https://www.actuaries.org.uk/system/files/documents/pdf/0233-0246.pdf. For an interesting comment by C. F. Wood see: https://www.actuaries.org.uk/system/files/documents/pdf/0278.pdf.Pharr, Clyde (1885-1972) [translator and editor), The Theodosian Code and Novels and the Sirmondian Constitutions, New York: Greenwood Press, 1969. Originally published by Princeton University Press, 1952. For the Latin originals, see: https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/Codex_Theod.htm.

Sanders, Henry A[rthur] (1868-1956), Roman Historical Sources and Institutions, New York, New York: Macmillan, 1904. Pp. 302-303 contain a list of Roman inscriptions relating to actuarii (actarii) from the reigns of Hadrian through Constantine. Sanders notes that those from the reign of Hadrian refer to the office of optio ab actis rather than actuarius. The earliest inscriptions with actarius or actuarius were cited by Sanders to the reign of Septimius Severus (reigned A.D. 193-211). Available at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Roman_Historical_Sources_and_Institution/284eAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Smith, William (1813-1893), William Wayte (1829-1898) and G[eorge] E[den] Marindin (1841-1939), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, London: John Murray, 1890-91 (2 vols). For Acta Senatus, see: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0063%3Aalphabetic+letter%3DA%3Aentry+group%3D1%3Aentry%3Dacta-cn.

Young, T[homas] E[mley], B.A.

(1844-1933), “The Origin and Development of Scientific and Professional

Societies, with their bearing upon the Institute of Actuaries and its

associated Profession: A Presidential Address delivered before the Institute of

Actuaries on the 29th of November, 1897,” Journal of the Institute of Actuaries (vol. 33, January 1898), pp.

453-485. See especially “Appendix: The Title of Actuary,” pp. 480-485. Young

was president of the Institute of Actuaries in 1896-98. Available at: https://archive.org/details/journal33instuoft/page/n5/mode/2up.

[1] De Orthographia 74:10. See https://latin.packhum.org/loc/1374/1/13#13.

[2] C.Th. viii.1.14 (Pharr 188).

[3] Nov. Valent. 7 (Pharr 521); Maj. 4 (Pharr 553); Marc. 2 (Pharr 563).

[4] C.Th. xi.26.2 (Pharr 317).

[5] C.Th. xi.8.2 (Pharr 302).

[6] C.Th. xiii.11.4 and 10 (Pharr 402).

[7] C.Th. C.Th. viii.10.4 (Pharr 210); vi.29.11 (Pharr 145).

[8] Nov.Th. 45(1) and (2).

[9] Nov.Th. 45(2).

[10] C.Th. I.11.2 (Pharr 23); C.Th. xii.6.23 (Pharr 372).

[11] C.Th. xi.8.3 (Pharr 302).

[12] Titles (all commencing with Actuarius Peccans) and their respondents include Circa Inquisitionem Generalem (Johan Gottfried Hilliger) (1737), In Causis Injuriarum (Thomas August Wolff) (1738), In Caussis Appellationum (Johan Caspar Seidler) (1739), In Formandis et Conscribendis Actis Judicialius Quoad Caussas Civieis (Carl Gottfried Muller) (1740), In Possessorio Summariissimo (Georg Christoph Franke) (1740), In Actu Torturae (Adolph Gottlob Friedrich Conradi) (1743), Compositione Amicabili Tentanda (Friedrich Nikolaus Rosenkrantz) (1746), De Inspectione Cadaveris Ante Sepuluram (Friedrich Heinrich Mylius) (1749), In Constitutiones Imperii et Saxonicas Contra Furas et Raptores Promulgatas (Carl Ehrenfried Brescius) (1754).

[13] Edward Rowe Mores has FamilySearch ID M3HY-Q5B. Much of the information concerning his family comes from his FamilySearch tree. He was born on Jan. 13, 1730 (N.S.) in Tunstall, Kent and died on Nov. 28, 1778 in [Low] Leyton, Essex. The fullest biographical information on Mores appears in Carter and Ricks, “Introduction,” Mores-2, pp. xiii-lvii. An autograph letter of Mores to Benjamin Franklin dated June 7, 1773, is preserved at the American Philosophical Society: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-20-02-0135.

[14] Date of death from Carter and Ricks, “Introduction” (Mores-2 p. l).

[15] Edward Jr. (1757-1846) and his second wife Sarah Rowe had children: Elizabeth Mores (1797-1868); Caroline Mores (born 1798) (married Herman Schroeder Cousins); Edward Rowe Mores (1800-1850) (married Maria Martha Marsden); Selina Mores (1803-1884); and William George Mores (1806-1870) (married Josephine Caroline Janssens). In their FamilySearch trees Edward (1757-1846) and his son Edward (1800-1850) share the same date of death, Mar. 22, 1850; however, this date is probably in error for Edward (1757-1846).

[16] Mynde engraved a full-length portrait of Mores for the frontispiece of Mores’ Nomina et Insignia (1749) (reproduced, Mores-2 p. xviii).