By John Divine

For the vast majority of human history, our species had no interaction with the skies. Perhaps the most serious entertainment of the subject for millennia on end appeared in a cautionary Greek myth. Alas, things didn’t end well for poor Icarus.

Airspace, it was thought, was for the birds.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that man began to successfully explore the extremes of the vertical dimension. And with new technologies came new society-level debates.

These debates took the familiar form of weighing costs versus benefits. Let’s first take a look at the most stratospheric devices mankind has put into the air, then work our way back down toward the terrestrial plane.

Space and low-earth orbit

Generally speaking, the rockets, satellites, and manned space missions brought about by the Space Race of the 1950s and 1960s proved to be less controversial than aerial pursuits closer to ground. After all, NASA didn’t need to put bustling airports in every major metro area—launches largely took place on the Florida coast, and were relatively rare events.

Still, the space program did have some broad costs borne by all of society. The first was the literal cost of the program; NASA was and is 100% taxpayer funded, and since NASA’s foundation in 1958 there have been detractors arguing space exploration is a waste of taxpayer money. Over the years, this chorus has gained some ground. In fiscal 1966, the U.S. allocated 4.41% of its federal budget to NASA; by fiscal 2020, only 0.48% of federal spending was earmarked for NASA.

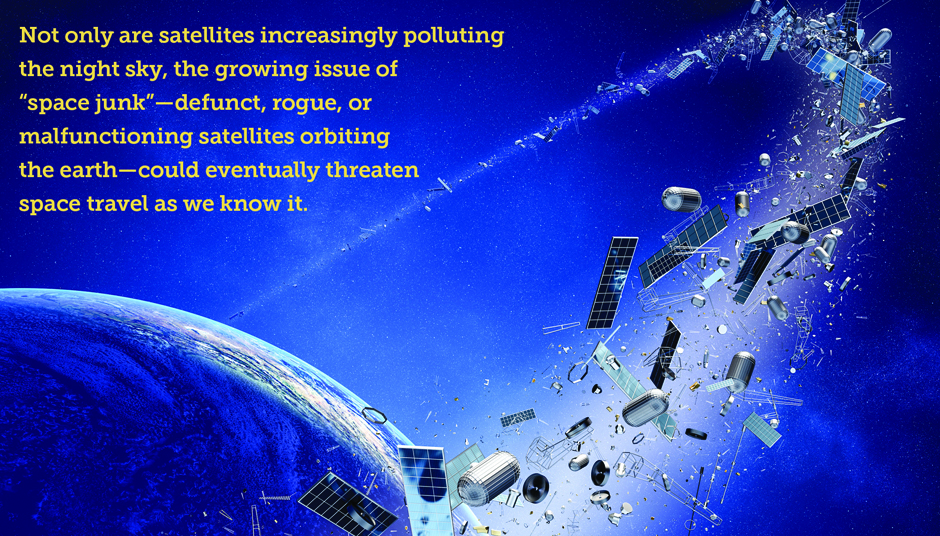

Criticism over light pollution caused by satellites has also grown over the years, as the number of devices in orbit continues to rise. The Union of Concerned Scientists pegs the number of operational satellites at nearly 3,400 right now—a fleet that’s already earned the ire of astronomers increasingly noticing satellites ruining their observations.

Currently, satellite advocates are winning the debate however, with Elon Musk’s Starlink alone already getting the green light for 12,000 satellites in an effort to bring internet to remote parts of the world. Amazon is seeking to launch 3,200 satellites for the same reason.

Although the rewards of going to space are certainly game-changing—GPS, communications, espionage, exploration, and eventually the colonization of other planets—these endeavors aren’t without drawbacks.

Not only are satellites increasingly polluting the night sky (and yes, they can be visible to the naked eye), the growing issue of “space junk”—defunct, rogue, or malfunctioning satellites orbiting the earth—could eventually threaten space travel as we know it. Given the high velocities of spacecraft and satellites, even hitting a 1-centimeter piece of debris could be catastrophically destructive to the unlucky object encountering it.

NASA says the concern here is that just one high-speed collision could set off a chain reaction as a destroyed object in orbit shatters into many tiny pieces that go off to collide with other objects, eventually surrounding the entire planet with enough space junk to confine mankind to Earth indefinitely, and potentially destroying global infrastructure and communications abilities we take for granted.

30,000-foot view: planes

In contrast to the sometimes arcane issues facing spacefaring craft, airplanes have undergone a far more thorough vetting by society. The CIA World Factbook pegs the number of airports across the globe at 41,820.

The cost-benefit over the years has only grown more favorable. Few and far between are Luddites demanding the end of air travel; noise pollution is pretty minimal and largely confined to a small radius around airports, and the aesthetic cost to the natural beauty of the skies is similarly muted, as planes typically reach cruising altitude mere minutes after takeoff over 30,000 feet above ground.

The benefits, society has broadly deemed, of facilitating global commerce and making long-distance travel affordable and convenient—not to mention the vastly superior safety of planes over automobiles—far outweigh the minor costs borne by those living near airports, although emissions are justifiably earning more scrutiny as the global climate crisis worsens.

But when it comes to aerial passenger vehicles, until very recently we haven’t been putting much new into the air. If anything, we’ve been taking things out. The famed supersonic Concorde airliner, which first hit the skies in 1976 and was retired in 2003, flew at twice the speed of sound and made the trek from New York to London in just under 3 hours; Londoners could hop on a flight in the U.K. and arrive stateside earlier than their departure time.

Ultimately, however, the prohibitive cost of supersonic travel, combined with slumping demand in the wake of 9/11, a highly publicized fatal crash in 2000, and complaints over noise pollution from sonic booms made supersonic transit uneconomical.

Although Jay-Z’s exhortation to bring back the Concorde has fallen on deaf ears, innovations in airspace at large are in play again. First, and most immediately, with drones. But lagging not too far behind are vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) vehicles and electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) vehicles. Flying cars, in approximate terms, with human passengers.

But first, drones:

Drones

Drones are the newest meaningful entrant into our shared airspaces, bursting onto the scene in the last decade.

These low-flying, lightweight devices tend to have a small radius of operability. They began growing popular as a way to gain unique, often gorgeous aerial footage that was previously inaccessible to the average Joe. Over time, sports like drone racing even emerged. Today, drones remain largely recreational. That last point is important to understand.

The role of drones in future airspace will largely be colored by the breakdown between recreational and commercial users.

And today, the recreational market is roughly triple the size of the commercial market.

The FAA last released a 20-year projection of how the aerospace sector would progress in 2020 with the release of the FAA Aerospace Forecast for fiscal years 2020 through 2040.

By the end of 2019, there were around 990,000 recreational drone operators registered with the FAA. All unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) weighing between 0.55 and 55 pounds are legally required to be registered with the FAA. With civil penalties up to $27,500—and criminal penalties up to $250,000 and three years in jail—for unregistered drones (citation), the incentive for operators to register is high, so that operator count should be pretty accurate.

Still, unlike the commercial market, not all recreational UAS models are required to be registered; only operators themselves must register (p. 47). Using sales data and other research methods, the FAA estimated the size of the actual fleet of recreational aircraft to be about 34% higher than registrations, at 1.32 million.

That number may be difficult to put into context, but this stat should help: The number of estimated recreational small unmanned aircraft systems (sUAS) grew by just 6.4% between 2018 and 2019, and the FAA projected decelerating growth in that area moving forward, too. Between 2019 and 2024, the FAA only expects recreational sUAS to grow from 1.32 million to 1.48 million. (p.48).

Although decelerating growth isn’t an alien phenomenon to newer technologies, the recreational drone market has matured with surprising rapidity. Between early 2016 and the beginning of 2018, the number of registered recreational UAS operators roughly doubled from around 400,000 to around 800,000 (p.46). If the FAA’s recent projections are remotely reliable, that 800,000 number may not double until the latter half of the 2020s—if at all.

The FAA credits the growing affordability of drones, alongside improving technological features like better cameras, more capable sensors and advances in maneuverability, for rapid growth in the earlier years of adoption.

However, the FAA says,

“…similar to all technologies including hobby items, (e.g., cell phones and video game consoles; and prior to that, video cameras, and video players), the trend in recreational UAS has been slowing and is likely to slow down further as the pace of falling prices diminishes and the early adopters begin to experience limits in their experiments, or as eagerness plateaus.” (p.48)

In fact, the FAA boldly states that it expects the recreational UAS market to saturate at 1.5 million units. It sounds more like the bleak growth profile of a long-established product like soda than the outlook for one of the most exciting newly accessible technologies in the last decade.

Don’t expect your skies to be full of your neighbor’s drones anytime soon—no noticeably fuller than they are today, at least.

But while the recreational market is larger, that dynamic is starting to change.

The growth profile of commercial UAS is much more attractive, roaring from 11,128 registrations in early 2016 to more than 385,000 by the close of 2019. The number of registrations rose by 44% in 2019, showing rabid demand compared to the recreational market’s 6.3% growth the same year.

More importantly, the FAA sees meaningful growth going forward too, expecting that 385,000 figure to jump 115% to 828,000 by 2024.

The agency hasn’t issued projections beyond 2024, but it seems clear that minimally, most new drones in the air will be commercial drones.

Companies like Amazon and others are getting FAA guidance and clearance to develop drone programs for various uses, with tantalizing potential for commerce and delivery. With a track record of being a first-mover in innovative future technology including e-commerce itself, eBooks, cloud computing, artificial intelligence and virtual assistants, Amazon’s interest in drones could foreshadow the eventual mainstream acceptance of these buzzing machines.

Consider Amazon’s jobs website, which features around four dozen open positions involving drones that the world’s leading e-commerce company is currently hiring for. For one position, “Software Development Engineer—Prime Air,” the company doesn’t bury the lede:

“Amazon Prime Air is making 30-minute drone delivery a reality. Prime Air will deliver a fleet of vehicles; manufacturing and maintenance operations; autonomous controls; fleet management operations; and airspace integration.”

So while recreational drones were first on the scene and commercial drone usage is heating up, the next, newest entrants into the skies are the VTOL and eVTOL—two crafts that, once here, could reshape transportation.

VTOLs and eVTOLs

Finally, what might generously be dubbed the age of flying cars is coming to the fore. Carmakers are increasingly getting into VTOLs and eVTOLs, with GM recently unveiling virtual plans for what amounts to a flying car at the vaunted annual CES event.

Technically, vertical take-off and landing technology has existed for over 80 years, since the invention of the helicopter in 1939.

In the eight decades since, societies across the world have run a cost-benefit analysis on helicopters, and frankly, there’s never been a time the helicopter threatened to clog our airspace. For starters, the noise pollution isn’t negligible; Purdue University estimates a Bell J-2A helicopter 100 feet away is around 100 decibels, making it about as loud as a power lawnmower. In short, it’s obnoxious, as anyone who’s been near one can testify.

Add to that the fact that a quality preowned heli typically runs north of $1 million, and it’s understandable why choppers are far more prominent in Schwarzenegger movies than day-to-day life.

But drones, incidentally, are a far more natural evolutionary step on the path to the burgeoning VTOL and eVTOL market. These craft are essentially just larger versions of drone technology, and unlike helicopters, these machines don’t come with obnoxious noise pollution.

Imagine a very large drone, made to carry one or more people—that’s essentially what VTOLs do, with most designs using many rotors and utilizing multiple redundancies so the vehicle won’t fall from the sky if an engine goes out. The technology clearly exists, it’s just new and expensive, and markets haven’t come together around a central design.

The emergence of VTOLs isn’t totally frivolous. In 1950, 64% of Americans lived in urban areas. Today, that number is around 83%, with nearly nine in 10 Americans expected to live in urban areas by 2050.

Ride-sharing helped revolutionize transportation. Even Segway and scooter services have popped up in urban areas as urban congestion drove demand for more convenient short-distance commutes.

The most compelling use cases for VTOL craft, at least in the early going, will be in large metropolitan areas with poor transportation. Los Angeles, for example, where traffic is famously terrible, would be a natural city for an early-stage rollout of the technology. New York? Fuggedaboutit! No U.S. city is more chock-full of wealthy businesspeople and VIPs on the go.

And anecdotally speaking, when people like Elon Musk speak, corporate America listens. His admonition of our domestic transportation system goes beyond the fossil fuels powering it all; he’s also chastised a collective decision to largely not make use of all three dimensions. One of his companies, The Boring Company, is digging tunnels to make it happen beneath ground, but there’s room in the skies, too. Plus, never underestimate the power of pop culture and sci-fi. We were promised flying cars.

Auto manufacturers as well as upstart industry newcomers are taking note of the long-term arc in transportation, which is bending in the direction of cleaner, more convenient, and more efficient forms of travel on and beneath ground.

With the recent example of Tesla and its enormous market cap as a motivator—Tesla is worth more than the next seven publicly traded automakers put together, including the likes of established players like Ford, GM and Toyota—industrial giants are anxious to be first-movers in what might be the next cradle of innovation: air travel.

Here’s a look at some of the biggest movers in the emerging space:

GM (Cadillac VTOL)

Among the major automakers, GM’s VTOL concept video from 2021’s CES made it arguably the highest-profile carmaker to commit to the space.

Michael Simcoe, vice president of global design at GM, walks and talks throughout the video in front of a futuristic personal aerial vehicle (PAV).

“The vertical take-off and landing drone, or VTOL, is GM’s first foray into aeromobility. We are preparing for a world where advances in electric and autonomous technology make personal air travel possible,” Simcoe says. The vehicle, he continues, is for a moment when “time is of essence.”

“You’ve been at the office and now you need to get to a meeting across town. The VTOL meets you on the roof and drops you at the vertiport closest to your destination. It uses a 90 kwH EV motor to power four rotors as well as air-to-air and air-to-ground communications,” Simcoe says.

The Cadillac VTOL concept is a 1-seater, but a 2-seater concept is on the way.

Toyota

Toyota has no publicly announced direct VTOL plans of its own, but it has made a $394 million investment in Joby Aviation, one of the early pure-play VTOL companies.

It is thought that Toyota is actively developing large drone technology of some sort; in early 2020, a large experimental eVTOL cargo drone registered to the company was spotted.

Joby Aviation

California-based Joby is much further along in the development process for eVTOL vehicles than most other companies in this space and is one of the front-runners in the race to be the first North American company offering air taxi services to the public.

Joby’s eVTOL, far from just a concept, has six electric motors, a range of 150 miles and more than 1,000 successful test flights.

The company has been working on its piloted passenger aircraft for over a decade, and expects to have an affordable air taxi service in 2024.

Joby reached an agreement to go public via a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) called Reinvent Technology Partners. Reinvent Technology Partners is led by famed Silicon Valley investors that include Reid Hoffman and Mark Pincus, and the transaction will value Joby Aviation at $6.6 billion.

Elroy Air and Embraer (cargo-focused VTOL)

One of the world’s leading aerospace companies, Brazil’s Embraer, teamed up with well-named VTOL startup Elroy Air in 2020 in an agreement to develop an autonomous cargo-carrying VTOL.

The vehicle is intended to disrupt delivery trucks operating inefficient routes; it aims to deliver loads of up to 500 pounds over distances up to 300 miles.

Honda

At the 2020 CES, Honda debuted a video showing a conceptual future design for urban transport in 2035 and beyond including a Honda-branded VTOL with two rotors soaring over a cityscape.

The futuristic Honda flying vehicle is seen transporting its passenger from the top of a skyscraper—which boasts a VTOL passenger vehicle posted at each of its four corners—to a designated landing pad in suburbia.

Autonomously guided, it takes a direct path to its final destination, touching down in the middle of a cul-de-sac outside the desired home.

Although lacking in specifics, the short video reveals that Honda sees itself as a player in the future of air mobility.

The video also reveals that Honda clearly expects the adoption of VTOL vehicles to be much more mainstream than helicopters have ever been. The video envisions widespread societal acceptance of VTOL craft, which appear to move in and out of residential neighborhoods with regularity.

Several other cul-de-sacs allowing for VTOL operation can be seen in the same neighborhood.

Hyundai

Announced at 2020 CES, Hyundai teamed up with Uber Elevate to announce the development of an eVTOL named S-A1 aimed at transforming urban transportation.

Offering more impressive specs than many of its competitors, the eVTOL will go up to 180 miles per hour (mph) at altitudes of 1,000 to 2,000 feet. It will have a range of up to 60 miles and take from five to seven minutes to recharge. The debut model will be piloted, but it will become autonomous over time, and seats four.

According to the company, “Hyundai’s electric aircraft utilizes distributed electric propulsion, powering multiple rotors and propellers around the airframe to increase safety by decreasing any single point of failure. Having several, smaller rotors also reduces noise relative to large rotor helicopters with combustion engines, which is very important to cities.”

The Hyundai eVTOL looks to be co-branded with Uber, and has a real shot to be one of the first key air taxi services in the future.

Volocopter

Another of the early leaders in actually bringing an eVTOL to market, Volocopter expects to go live with air taxi services in 2023. The German firm recently raised 200 million euro in a Series D funding round.

CEO Florian Reuter expects Paris and Singapore to be the first two cities of operation, noting that Paris is anxious to have flying taxis in the air in time for the 2024 Olympics.

The current specs for its vehicle, the Volocity, allow it to carry two passengers. It’s all-electric, propelled by 18 rotors and powered by nine lithium-ion battery packs.

The current range is just over 21 miles with a max airspeed around 68 mph.

EHang

This China-based VTOL company is another early leader in VTOL, with a max payload of 485 pounds, a range of over 21 miles at full payload, and a maximum speed of over 80 mph.

Like Volocopter, EHang believes in building redundancies into its vehicles, allowing for the failure or malfunction of one of its rotors without dooming passengers. It will also be a fully automated craft.

EHang’s specialty is known as autonomous aerial vehicles, or AAVs, and the company’s craft are already in use in specialized industries in China.

Countries like Norway, China, and Canada have already approved the EHang 216 for various test flights and air logistics purposes.

Last year, the company debuted the EH216F, a vehicle the company calls “the world’s first large-payload AAV for high-rise aerial firefighting.”

Lilium

Another German company, Lilium, is racing to build its Lilium Jet eVTOL, the ambitious 36-motor five-seater it plans for the center of its urban air mobility (UAM) service it aims to launch in 2025.

The company is targeting a range of up to 186 miles and top speeds of 185 mph—specs that would make Lilium an early groundbreaker in eVTOL transport and enable Lilium’s larger dream of streamlining regional travel, connecting city centers in a cleaner, cheaper, and more convenient way.

The company recently announced a partnership with infrastructure operator Ferrovial to build out a network of at least 10 vertiports in Florida connecting all major cities in the state through zero-carbon infrastructure.

Remo Gerber, Lilium’s chief operating officer, said in a January 2021 announcement that almost all 20 million Floridians will live within 30 minutes of their vertiports.

The company has raised over $375 million.

The future is here

With so many companies investing heavily in the space—and a number of VTOL craft already making flights—the growth of this blooming industry is inevitable. It’s the degree of growth, and the eventual size of the market, that remains a question.

The most likely business model, at least in the early days of adoption, is one of an air taxi service—an elite aerial Uber for businesspeople and VIPs with demanding schedules in dense urban areas.

The military and law enforcement applications are also obvious. Imagine the bin Laden raid using quiet eVTOLs instead of noisy helicopters, or local police precincts with the ability to instantly take to the air to assist with developing crises.

Unlike helicopters, the more drone-like VTOL craft of tomorrow should be able to navigate freely without making nearly as much noise.

Especially as the cost profile of eVTOLs improves with battery technology, the affordability issue that contributed to the more limited adoption of the helicopter should improve. And the shared mobility revolution ushered in by companies like Uber and Lyft, when transposed upon the world of aerial vehicles, should also help with affordability.

The open question is safety. How much margin for error is there in these machines? How high up should they fly in order not to bother ground pedestrians, and how much additional danger does that create for both passengers and terrestrial pedestrians? If you’re driving and your engine stalls out, it’s not an immediate death sentence in all circumstances. If you’re in an eVTOL vehicle and there’s a machine failure at 100 feet, not only are the passengers going to be fatally wounded but there will be giant heaps of metal raining down from the sky.

Countries like China are already offering drone taxi flights around its Greater Bay Area in EHang crafts. It’s not yet accessible to the everyman though, with a flight from Shenzen to Hong Kong costing around $7,000—or the equivalent of about $9 per second.

Another big question to be answered is casualty coverage—who bears the risk? The Uber / Lyft model, in which independent operators drive for a central hub, is still being litigated in the courts when it comes to ultimate liability. Add in autonomous capabilities, connected fleets, and smart cities, and you have a whole host of questions to answer … questions actuaries will undoubtedly be called on to assess.

Actuaries would be wise to get ready to answer those questions sooner rather than later, though—the future of flying cars, long promised by sci-fi, seems finally to be at hand.

JOHN DIVINE is a freelance writer based in Charlotte, N.C