By P.E. Forte

For more than 30 years, private long-term care insurance (LTCI) has been sold as a way to pay for expenses that can break a family’s budget, strip a surviving spouse or partner of financial resources, or bankrupt an estate. Positioning the insurance in this way made good business sense at one time, but it tended to glide over the fact that long-term care (LTC) is a health event that can affect quality of life as well as threaten financial ruin. Every adult who has lived through the past year of COVID-19 with a family member in care recognizes that a person getting only custodial care—that is, supportive services—may at any time also require medical services for an acute health condition, such as that brought on by an infection. If the person is aged, medical intervention may be necessary due to other causes, such as a fall, fracture, or stroke, which require emergency measures, including hospitalization, intensive care, surgery, intravenous medication, and post-acute rehabilitative therapy.

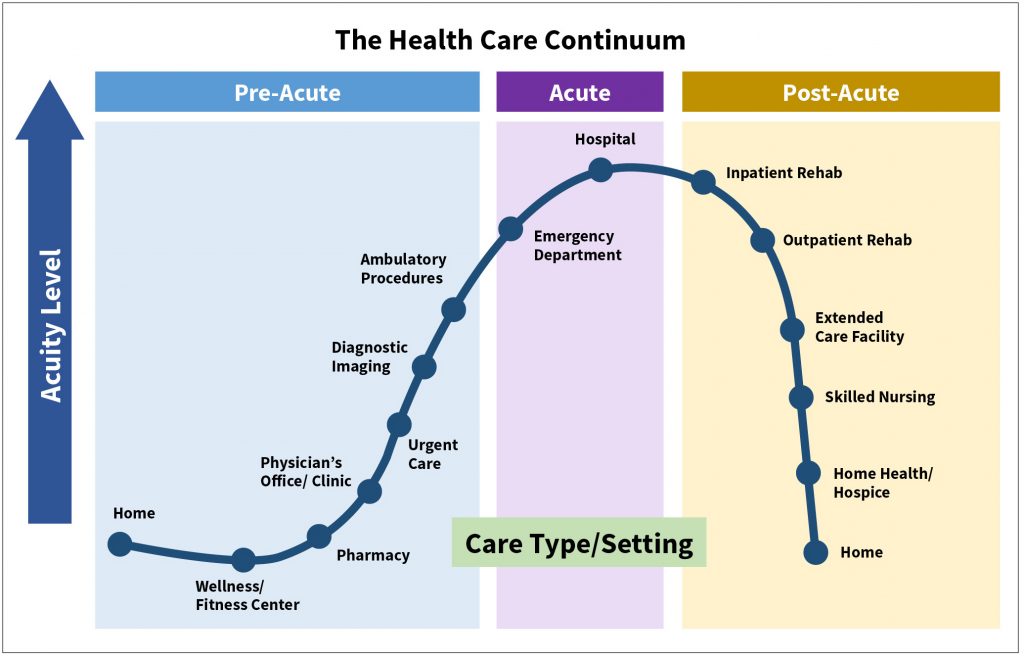

The biological evidence for considering long-term care as an aspect of health care is incontrovertible. The vast majority of all deaths today arises not from sudden illness in healthy people but from chronic debilitating diseases like adult-onset diabetes, arteriosclerosis, obstructive pulmonary disease (including emphysema), multiple sclerosis, ALS, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, cancer, renal failure, and cirrhosis. Such illnesses often have long histories, some stretching back to early adulthood. While SARS-like viruses can affect anyone, they are less likely to gain traction inside of the health care continuum—that congeries of consultations, examinations, screenings, prescriptions, protocols, and treatment modalities recommended by doctors and health professionals from childhood into old age—than outside of it. This is because timely interventions help to ensure that we maintain optimal health throughout life. It is well established that all systems within the human body are interconnected, and this linkage applies both to neural pathways and molecular structures, mind and body. Consistent medical attention is important therefore not only for preventing the worst acute care outcomes, but also for mitigating the risk of needing long-term services and supports, often in an institutional setting.

Because LTCI provides benefits geared primarily to safety, prevention, and daily living—as opposed to treatment—it might seem prima facie to be independent of the continuum being described, but that is not so. It is very much intertwined with the business of health care management, while the effect it has on health outcomes has consequences for LTC policyholders, their service providers, and those bearing the risk of related expenses. The services that LTCI covers—assistance with bathing, dressing, eating, transferring, and personal hygiene—are largely concerned with health maintenance. They are not merely concierge in nature, giving comfort or assuring convenience, although that is a part of it. Rather, they are critical to physical and mental well-being and therefore most advantageously situated within the health care continuum. Locating LTCI within that continuum means addressing all gaps in health and function that might open up from accident, injury, trauma, or lifestyle, and addressing these quickly and knowledgeably, so as to restore stability while there is still time to make a difference. This would mean a kind of realignment between LTCI and health care, putting them on the same as opposed to parallel tracks and creating closer links with employer-sponsored group health insurance, Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans, the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Affordable Care Act, the Older Americans Act, and other forms of health protection. The result would be greater synergy between LTCI and health care, which are now separated by a largely unexplored borderland in which no authority is in charge. This would mean, on the acute medical side, significant reductions in hospitalizations and emergency room visits that are disruptive and costly, and on the long-term care side, a reduction in the frequency and severity of long-term care events that might have been postponed or prevented altogether.

Let me note at the start what realignment would not mean. It would not mean incorporating LTCI benefits into health insurance, though that might be worth considering, nor adding LTCI benefits into some other form of health-oriented insurance coverage (say disability insurance or critical illness). And it would not sweep in some LTCI hybrid or combo products, such as ones that accelerate a life insurance benefit but do not extend LTC benefits after the life insurance benefit is exhausted. [1]

In the pages that follow I present what a realignment of LTCI and health care might look like, the advantages this structure would yield over the status quo, and the challenges that would have to be addressed. I also suggest why doing so might enable insurers to sell more policies with which they are comfortable and to ride the wave of interest being generated by improved personal health management and social LTCI. My focus throughout will be on stand-alone LTCI, because that is the form best fitted to the large middle class. But first it is necessary to go back to the very beginnings of the LTCI market and the events that shaped the product’s introduction.

1. Where we are, how we got here

LTCI was introduced in the wake of the passage of Medicare and Medicaid, two major programs of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiative. Medicare still provides for those 65 and older the greatest safety net with respect to short-term or acute health care—hospitalization, surgery, post-hospital rehabilitative care—and it does underwrite the cost of a considerable amount of long-term care, though it was never designed to do so. In fact, Medicare today absorbs billions in long-term care costs, usually from rehabilitative care where there is no reliable transition to ongoing care that is custodial in nature. Medicaid, on the other hand, provides cash assistance for health care and basic living expenses to lower-income young people, including women with dependent children, the blind, and the disabled who meet certain criteria. Medicaid initially made nursing home benefits available on a limited basis—100 days of nursing home care, 100 days of home health care visits—but became over time the default choice for extended long-term care services for the middle class, which lacked the resources to pay for them and soon found ways, with the help of estate planners, to qualify for benefits after spending down to the necessary minimum. In 2017, the most recent year for which we have data, Medicaid covered more than 50% of all long-term care expenses, with 57% of that going to home- and community-based services rather than institutional care. This allocation has reduced per capita nursing home spending considerably since 1988, the first year the expense was tracked, but Medicaid costs are still rising. In fact, Medicaid spending in FY 2019 for long-term services and supports across all 50 states and six U.S. territories was some $130 billion, a 6% increase over FY 2018.[2]

The earliest policies, which appeared in the late 1960s, were oriented to medical conditions: They based access to long-term care benefits on prior hospitalization, physician’s certification, and institutional care. Nervous and mental illnesses were excluded. Alzheimer’s disease and dementias were not covered unless co-morbid conditions could be medically certified. No wonder these products were criticized by regulators, care providers, consumer advocates, and consumers themselves. They simply did not square with the reality people were facing. Better received were the “second generation” policies introduced in the mid 1980s. Developed amid greater awareness of the increased life expectancy that had been achieved in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, and sensitive to the living challenges faced by the aged, these policies took account of cognitive illnesses by utilizing the Katz Scale of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) as a claim trigger (as opposed to prior hospitalization) and mental status tests to determine cognitive deficits.

LTC insurers were thus able to emphasize the custodial aspect of long-term care—the non-medical help with the familiar kinds of routine activities that healthy people take for granted but that many persons suffering from debility cannot do for themselves. That was an important factor for market adoption. Potential buyers immediately recognized the value of such coverage: It would pay for the services that they themselves had been giving to family members to ensure hygiene and enable continued functioning at a basic level.

Yet, a funny thing happened along the way. The movement of LTCI from medicine into custodial care came to be dominated by financial planning. Both first- and second-generation LTCI policies employed the general language of health insurance and the select terminology of disability insurance, on whose chassis LTCI was built, but that was largely for purposes of underwriting and claims adjudication. Once medical evidence had been gathered, submitted, and analyzed, and the policy was approved and put on to the insurance company’s books, medical issues were largely disregarded, not really in focus again until the insured filed a claim, which could be decades down the road. How the insured fared and behaved during that long expanse of time—whether there were regular consultations with physicians, whether prescribed treatments for certain diagnoses were being followed, whether recommendations for lifestyle changes were adhered to—was not really the insurer’s concern, unless the policyholder filed a claim soon after the policy became effective, within the standard two-year “incontestability” period. Then the insurer might dig deeper into the claimant’s medical history as provided to the underwriter, with rescission as the next step. Of course, if the claim took place after the standard two-year period, little could be done. Deliberate efforts on the part of the claimant to conceal information had to be proved, which was not easy. While there is yet no hard evidence that undisclosed medical conditions have had any appreciable impact on LTCI claims to date, the jury is still out as to whether gaps in the health record of millions of LTC insureds might not affect future claims experience.

It is worth pausing to revisit the context in which the decision to position LTCI as a financial product was made. The U.S. Census of 1980, which identified the “Graying of America,” underscored the increase in human longevity and its role in unleashing an age wave, the likes of which no country had before seen. In the first half of the 20th century, improvements in sanitation and public hygiene “drastically altered the national physiognomy of illness,” as Siddhartha Mukherjee explains, while new pharmaceuticals like vaccinia, penicillin, tetracycline, streptomycin, and the Sabin vaccine helped to eliminate infectious diseases such as smallpox, typhoid, tuberculosis, and polio, boosting the average lifespan from five to seven decades, so that by the mid-1980s, epidemiological advances had increased average lifespans to eight decades.[3] The post-World War II focus on how millions of children were to be nurtured, entertained, and educated shifted to concern about how those same children were to be taken care of in their later years. Aging spawned academic, economic, cultural, and even spiritual disciplines. Corporate marketing departments hired demographers whose statistics generated an excitement that compilers could hardly have imagined a generation earlier.

That life insurance companies would get into the action was a foregone conclusion. But these same companies were having less-than-satisfactory results in their health insurance portfolios. Indeed, many were withdrawing from the health insurance market, leaving the field to the new managed care companies and preferred provider networks that were making conventional health insurance uncompetitive. Exiting the health market was prompted by earnings, and became a kind of mandate for life insurance companies thinking about demutualization, as remaining in the health insurance business would have had adverse consequences for market valuation and stock price.

It was perhaps not surprising that life insurers developing LTCI products returned to the core disciplines of life insurance, because LTCI products involved a long lapse between time of application and time of claim, and that required actuarial expertise, including stochastic and deterministic modeling. Nor was it surprising that when insurers started to design LTCI products, they chose not term insurance but guaranteed renewable level premium funding. This mechanism allowed for the gradual build-up of reserves in the policyholder’s younger years when the risk of needing LTC was low so as to be able to meet obligations that would be more likely to arise in the future, while also stipulating that coverage could not be terminated provided the policyholder paid the required premium when due.[4] Such funding did impose certain restrictions. Long-dated liabilities were best matched to fixed income securities like bonds, which were less volatile than stocks, although the lack of securities with maturity dates comparable to the liabilities assumed was a problem. However, in the late 1980s and 1990s, bonds—both risk-free bonds (such as 10-year Treasuries) and corporate debt—had rates of return over 7%, with the possibility of higher yields through trades. Guaranteed renewable level premium LTCI thus provided assurance to those worried about making payments in their later years when living on tight budgets. Few at the time anticipated that “level premiums” would have to be increased substantially. Insurance executives assumed that LTCI blocks would experience a high rate of lapse, which would reduce liability and thus the need for reserve increases. Of course level premium also sidestepped the fact that LTCI would enjoy no subsidies from the government or the employer, which was the norm with health insurance, where rate increases were heavily subsidized and could therefore be masked.

The insurance company seller would be able to emphasize the discontinuity between acute care and long-term care, the often hidden costs of the latter, and the need to plan in advance for them, which made for a pretty strong value proposition. The cost of long-term care was high, even for the affluent, so the notion of transferring LTC risk to a third party made sense. LTCI could be included in any comprehensive estate plan. Agents could present LTCI as a helpful adjunct to other products, such as annuities, whose payouts could be undermined by an uninsured long-term care event. Commissions were attractive: most insurers on the individual side were paying some form of renewal commission for eight and even 10 years.

Group long-term care insurance contracts followed on the heels of individual policy sales. The former were not positioned as part of estate planning, however, because group LTCI contracts did not offer the kind of one-on-one counseling that a fully licensed agent could provide, and anyway group contracts typically limited commissions to one-time fees based on initial enrollments. Nevertheless, the group contract could be presented as something that any employee wishing to have a secure retirement should consider and any responsible employer should sponsor.

By the mid-1990s, several hundred Fortune 1000 companies had implemented group LTCI plans, most on a voluntary, fully contributory basis, though some private law, investment, and consulting firms offered subsidies. Colleges and universities also made group long-term care insurance available, as did national associations like AARP, and a number of state governments. By the turn of the millennium, LTCI had become a major business line of life insurance companies, with more than 100 insurers offering some form of it and third-party administrators springing up to provide outsourcing assistance where the insurer did not wish to invest heavily in operations. Not surprisingly, retail (individual) policy sales, which paid such generous commissions, jumped out ahead of group sales and have maintained a solid lead in sales volume ever since. Even today, of roughly 7.5 million policies in existence, two-thirds are individual.

2. Disadvantages of the current approach

Positioning LTCI as a financial product created a positive competitive environment for product innovation and much commercial excitement. But there was a trade-off that drew no comment, largely because it was not really deemed that important at the time. This was the effect of the absence of any strong linkage between acute or short- and long-term care. Early policies were criticized because of their medical orientation, which, as noted, missed the custodial nature of much long-term care. But making finance the basis of the LTC decision meant removing it from the context in which it was best understood and managed—namely, health care. There was a lot of talk about lifespan and how it had increased, requiring long range planning, but there was little or no attention given to healthspan: the years of good or better-than-average health that everyone desires. Moreover, not much attention was given to wellness, which aims at improving overall health by educating people about diet, sleep, exercise, stress, the environment, and other factors that have an effect on long-term health.

This dialogue was already underway in health insurance, especially in employer groups, which were seeing the costs associated with ignoring wellness, but it did not take hold in LTCI. This was partly because it was hard to prove how there could be linkage between the behaviors of applicants and their actual health status when separated by decades, and partly because LTCI was already quite complex, and it would have been a stretch in the early stages of the product’s history to incorporate a means by which the policyholder’s knowledge of and participation in decision-making related to health could be reflected in the health outcomes of one’s later years.

Thus, after the time of application for coverage, the insurer had little sightline into diseases that were largely the result of lifestyle and behavior, such as adult-onset diabetes, obesity, arteriosclerosis, heart disease, circulatory disorders, and various forms of cancer that could worsen general health and went largely unmonitored. In any case life insurers were not tuned into medical research and development, so they were not fully aware of important advances in medicine and technology that could affect morbidity and mortality in the future, such as hematology, chemotherapy, and biogerontology (replacing aging cells that cause impairment and failure). These were not the insurance company’s affair, though they would certainly have consequences for bottom-line results down the road, as health problems that develop in middle age and later can result in conditions that persist and worsen through the end stage of life, impairing mobility, impeding cognition, and shutting down organs. The failure to integrate the insights and data arising from the management of changing health risks over the many decades of a person’s life—in truth, a kind of isolationism—has come at a cost.

Given developments in medicine and technology in the past 20 years, especially the digitization of health care data, we now know there is an appetite for participation and decision-making on the part of insureds, many of whom are willing to engage in healthy habits—if given tools or incentives to do so. Digital tracking devices like Fitbit and Apple Watch enable millions to take stock of data pertaining to exercise, diet, sleep and other factors that influence long-term health. Using that data, they can better manage their risks of developing serious health conditions.

Some companies offer incentives for healthy living. Vitality Health, a subsidiary of Discovery Holdings, a global insurance provider, rewards people for healthy living by means of data sharing and analysis, which is used to establish baseline health and then to create a personal plan. Progress against that plan is determined by integrated data feeds from various sources with which the client interacts; points are awarded for that progress. John Hancock awards premium credits on life insurance products through its “Vitality” program to those who can furnish regular evidence of healthy lifestyle choices, and those choices can result in discounts on purchases that support them.

If the disconnect between health care and private LTCI had significant consequences for the individual policyholder, it must be assumed that it was vastly greater when viewed across the industry and the national economy. The U.S. spends more per capita on health than any other country by a wide margin yet enjoys only mediocre results. In 2021, the U.S. health care system was ranked last among 11 industrialized countries by the Commonwealth Fund, falling behind the U.K., Norway, France, and Canada with respect to population health, access, efficiency, equity, and quality. The separation of acute and long-term health risk is merely one aspect of this lackluster performance, and few would say it is the primary factor. But insofar as the costs of health care in the last decade of life are greatly disproportionate to every other, it is a marker worth noting.

Yet another unexpected development that has affected the success of LTCI was changing actuarial assumptions. These have resulted in numerous rate increases, which have dominated discussion within the LTCI market since 2000, affecting the policyholders who have had to pay them or have had to reduce their benefits, the state department regulators who must hear complaints from those policyholders but also want to ensure that insurers remain solvent, the insurance executives who must work hard to persuade regulators that the increases are needed, and the elected officials who try to disentangle the issues brought before them. While a realignment of LTCI with health care would not have prevented such rate increases from occurring if it had come about sooner, an argument could be made that the industry’s focus on LTC as a financial risk has made the problems associated with rate increases harder to correct.

Consider the promise of a fully insured defined benefit. Such a problem falls directly in the life insurance company’s wheelhouse. However, a fully insured LTCI benefit must be secured over decades without actual knowledge of future claims patterns; what modes of treatment might be available for those suffering from degenerative illnesses; how lapse, morbidity, and mortality rates may change; how securities markets will perform; and changes in the cost of care. Alignment with health care might have enabled the postulation of a different model of funding, and different approaches to managing it. Health care costs rise constantly and require numerous contingencies to manage them. Risk-sharing is common and commonly accepted, involving deductibles, co-insurance, and the like. Conventional LTCI does employ risk-sharing techniques, there usually being no cash value or death benefit available; still, conventional LTCI is predicated on paying a defined daily maximum benefit and a defined maximum lifetime benefit. It would make more sense to target within certain parameters approximate amounts of coverage that should in most cases be adequate but could fall short, which is the case with almost all good insurance policies, which aim at covering the greater part of the risk for which they are written, but not necessarily all of the risk. While allowing benefits that fluctuate in value as experience emerges might have caused greater uncertainty at time of purchase and perhaps subsequently, most LTC insureds are not able to exhaust their benefit pools. Yet they must pay for them over the many years that usually precede the time of claim, and they must often pay large premium increases as long-term actuarial assumptions change or reduce their benefits, weakening the value proposition. Contrast this with a variable benefit pool, which would make possible a lower premium, less protracted waiting periods, lower capital requirements, and premium rate increases that would be smaller in size, but perhaps more frequent.[5] The shift from fixed benefits to variable ones could be managed within the current context of LTCI as a financial product, but acceptance of the shift by consumers would be more likely if the product were cast within the ever variable framework of health care and health care pricing, which is continuously evolving.

3. Challenges of realignment

Realigning LTCI with health care would not solve all of the problems described above, nor would its realization be quick. Indeed, if attempted, it would likely take decades to implement. But it would begin a process by which all stakeholders could be re-oriented to the ground that gives shape to most of the responses we make about LTC as a major risk, and that is health care.

The first challenge would be for the pricing of LTCI products to take into account certain developments in medicine and medical technology not being followed today. In addition to tracking and analyzing their own insured data, insurers would pay attention to the massive amounts of general population health data being aggregated daily and soon to be captured in electronic health records. Actuaries would need to take stock of areas of medical science that have not been part of the actuary’s toolkit in the past. Data from immunotherapy, surgical intervention, pharmacology, telemedicine, and assistive technology—all of which will affect morbidity and mortality rates in the future—would also be considered. In certain instances, data from the experience of foreign countries might be useful. In Japan, for example, significant advances have already been made in using robotics to supplement the work of caregivers, both in institutional and home settings. The integration of robotics into regular daily care routines in the future could reduce reliance on human caregivers here in the U.S. and allow more people to function independently for longer periods of time.

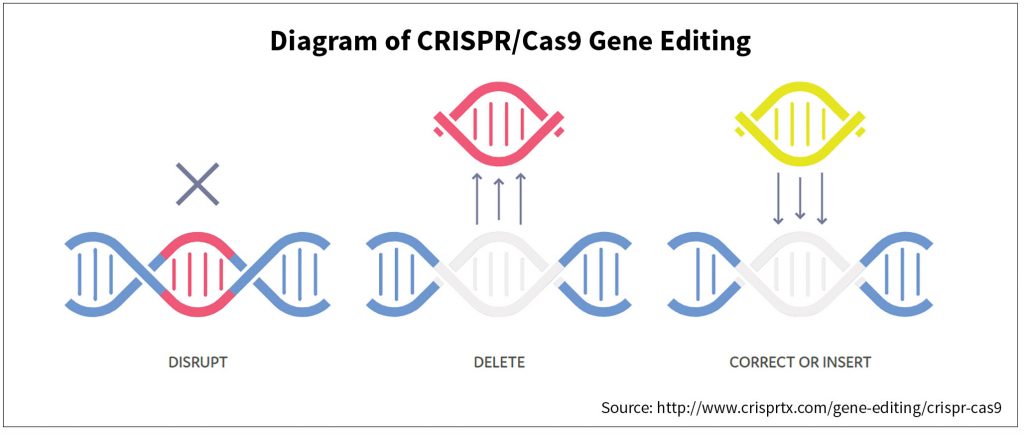

Then there is clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs), a field of biotechnology that derives from genomic research. CRISPRs are parts of the bacterial immune system that can be programmed to target specific stretches of the genetic code and to edit genes within a cell that cause certain malignancies and other health crises. It is almost certain that LTC risk assessments will have to take account of developments in this field of research. As early as 1980, James Fries was talking about the “compression of morbidity” likely to result in the future due to the eradication of many infectious diseases that had killed prior generations, leaving more of us alive in a healthy state for longer, while also reflecting the fact that the human genome did not program us to live much beyond the century mark, if we reached it at all.[6] Failure to regain homeostasis after a serious illness such as pneumonia meant that we were likely to die after a shorter period of time, thus “compressing” the period of senescence (and dependency) near the end of life. But if people are able to live independently in reasonably good health for longer periods of time, and then unable to recover from a severe health crisis, the claims experience of LTC insurers will be different from what some actuaries are assuming now—namely, that people in advanced age will become debilitated for longer and longer of periods of time, unable to resume independent living and unable to die.

Some contend that if everyone lives on average longer there will be more of us alive to get Alzheimer’s and other diseases incident to old age, but this is not necessarily the case. There are far more centenarians now than in years past, and many enjoy quality of life. Progress is being made with respect to neurodegenerative illnesses causing physical and cognitive impairment. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) via implanted electrodes has helped thousands of people suffering from epilepsy, essential tremor, Parkinson’s disease, and other movement disorders to control symptoms. New drugs like Biogen’s aducanumab (Aduhelm), a monoclonal antibody that targets amyloid beta plaques in the human brain, are now available for Alzheimer’s patients and dementia patients in clinical trials. Also notable is the research that is delving into the root causes of cognitive decline, and then working to address them in a personalized precision medicine approach that considers a range of risk factors for each Alzheimer’s patient.[7]

Another challenge would involve the reconsideration of premium structure, both with respect to initial premium and rate increases. Level premium funding is not the only way to write LTCI, but it does allow for pre-funding, something simply not available in any form of term.[8] However, premiums that rise over the years by step rating may now have greater appeal, especially with more people working longer than in years past. Premiums could be made affordable even if increased during working years, and might be manageable if stopped at age 70, which will soon become the new retirement age. With respect to rate increases on existing policies, phase-ins might also be the more desirable arrangement. State insurance departments have repeatedly inquired about phasing in premium increases. It is also possible to phase in rate increases before there is evidence that an increase is needed and then reconcile any difference between what has been paid and what should have been paid based on actual experience. Subsidies or pre-funding may be required, as noted previously. Such a schema would alleviate the problem of people facing very high increases at a single point in time, especially in their later years. The structure of LTCI pricing would then be somewhat closer to that of health insurance. And if there were closer association in the public’s mind between the two, government and perhaps even employer subsidies might be feasible.

Tax treatment of premiums and benefits would be still another challenge. Under HIPAA section 7702 (b), LTCI has been filed with insurance departments as “Accident and Health Insurance Coverage.” This has given it relatively mild treatment: long-term care benefits are exempt from taxation as income and premiums cannot be deducted unless they constitute more than 7.5% of gross taxable income under the current code. The Long-term Care Affordability Act introduced by Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA) would change this by allowing LTC policyholders to pay up to $2,500 per year for long-term care insurance out of their 401(k), 403 (b), and IRA without a tax penalty. If private LTCI were to be aligned with health care, logic would dictate that it be filed along with other health products. Doing so would mean significant tax advantages, because health insurance premiums are treated under the current IRS code as a medical expense and therefore deductible unless the individual is receiving government subsidies, as is the case with some persons under ACA. In employer-sponsored group insurance arrangements—health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and preferred provider organizations (PPOs)—health insurance premiums enjoy pre-tax treatment. This is not true of employer-sponsored, fully contributory group LTCI, which has not been granted pre-tax treatment authorization.

Clearly, allowing LTCI to enjoy the same tax treatment as private health insurance would be a plus both for the individual buying it and for insurance companies selling it, as it would reduce the cost of a policy. However, a fresh cost/benefit analysis would be necessary. Proposals to make LTCI eligible for an above-the-line tax deduction have been submitted to Congress for more than 20 years, and they have never received much support, owing largely to the scoring that projects large amounts of lost tax revenue. Still, these are different times. In an era of massive stimulus programs, when health care has been urged by some as having a place in a national infrastructure revitalization plan, the tax treatment of LTCI may get better traction, especially as the baby boom generation enters the final phases of its life and the cost of Medicaid, the principal payer of long-term care expense in the country, continues to rise.

Marketing the new health care-aligned LTCI product would also be a challenge. Confusion could result from the closer connection between LTCI and private health insurance. As noted, LTCI has been sold as protection for what Medicare, Medicare Supplement, and other private health policies do not cover, so those with existing LTCI policies could conclude that the LTCI policies they hold are redundant. Thought would have to be given as to how to overcome this problem, and that would have to be done incrementally over time. A new educational emphasis would be required on the continuity of health care and long-term care, not its discontinuity and lack of connection.

4. Opportunities of realignment

To summarize what a realignment would mean in practical terms: First, it would mean a change of course to the core value proposition of LTCI—why we buy it, why we need it. Second, it would mean identifying it more closely, at least in this context, with other forms of insurance, private and public, that protect us in case of illness. Third, it would mean a much stronger emphasis on wellness, on emerging health data, and on utilizing medical and biotechnical science. Finally, it would have implications for LTCI financing and pricing. This is because such a movement would shift LTCI away from delivery via an unchanging guaranteed renewable product toward one in which both benefits and premiums are variable, to be determined not in a particular moment of time based on insured data gathered in the past but rather from a process that draws on emerging data from numerous disparate sources and studies trends over time. Such a shift might require some kind of pre-funding or subsidization of the old by the young, since the risk of needing LTC rises exponentially with age. On the other hand, the new synergy described above could change the arc of all geriatric insurance risks. In any case, the changes I am describing would not take place all at once but would rather be part of an evolution that is integrated with advances in health care and technology.

It would all take work. However, the new alignment being proposed here would have distinct advantages. Life insurance companies would benefit from the linkage with respect not only respect to new sales but closed blocks. Millions purchased LTCI in their mid-40s and 50s during the past 20 years, and their health outcomes are not yet determined. Greater education and awareness of better health habits could improve late-life health scenarios, while the ability to maintain an independent lifestyle could have a dramatically positive effect on insurance company underwriting experience, reserving, and related premium rates. This would lessen actuarial gymnastics of one kind or another, because long-term care insurance would be seen within the context of health maintenance.

Health insurance companies—which are already absorbing long-term care risk due to the frequency of hospitalization, surgical intervention, and diagnostics—would also benefit. Health plans could see reduced incidence of emergency room visits, intensive care unit utilization, and expensive rehabilitative therapy.

There is also the awareness that will be generated by the public sector’s establishment of basic long-term services and supports (LTSS) programs. The state of Washington will implement the very first tax-based program in the nation for LTSS effective January 1, 2022. California, Minnesota, and other states may follow suit for the reasons already given—and also to relieve the heavy LTC financial burden carried by Medicare and Medicaid by state as well as federal governments.[9] Behind them lie decades of efforts at legislating public funding of long-term care services, including H.R. 2762, The Medicare Long-Term Home Care Catastrophic Protection Act of 1987, which was championed by Rep. Claude Pepper (D/FL-18), and The Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) Act of 2014. These efforts were flawed in design and ultimately defeated on their purported lack of sustainability, but the time may be coming in which measures comparable in scale are viewed as both compelling and fiscally defensible. Such measures, if enacted, will almost certainly position social LTCI as a kind of health protection. This could in turn lead to a reduction in overall spending on health care per capita, or at least a slowing of its rate of growth, which in turn would make more funds available for other important social, economic, and environmental needs. With health care increasing as a portion of GDP each year—Congressional Budget Office estimates suggest it will exceed 20% by the end of this decade—it is evident that health care spending is crowding out other vital needs of our society.

The original positioning of LTCI as a financial product was not wrong; it was just not adequate to the task. Life insurers offered people valuable protection against a risk that was otherwise uncovered by public health programs and traditional lines of private insurance, and it helped spawn a new insurance industry. But presenting LTCI as financial protection rather than health maintenance has limited the value of LTCI as a consumer purchase.

The good news is that LTCI has not yet run its course. It is still quite early in the history of the management of the risk. Life insurance required more than 150 years to be established firmly, not really taking root as a mainstream protection product until after WWII. Private health insurance took decades to stabilize. The realignment proposed here is not a panacea. But it is a starting point for reform and one that could benefit a range of stakeholders—consumers, insurers, health care companies, state and federal governments, investors. It would be a shame to trundle along the same old gloomy path, limiting ourselves to closed block management and maintenance administration, when a new paradigm might be adopted, indeed when life in this country itself is being reimagined and, hopefully, transformed for the better.

Paul Forte is a 40-year veteran of the life insurance business, serving in the last 20 years as Chief Executive Officer of Long Term Care Partners, LLC (now doing business as FedPoint), which administers the Federal Long-term Care Insurance Program (FLTCIP), the nation’s largest private LTCI program. He wishes to state that the opinions contained in this piece are his and his alone and do not reflect the views of FedPoint, its parent John Hancock Life & Health Company, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, or any other federal government agency. He wishes also to acknowledge Jon Seder for editorial and graphics assistance, and Marc Cohen, Nick Latrenta, Roger Loomis, Dave Martin, and Mike Young for their close reading and comments.

Steps that could help LTCI more closely align with health care

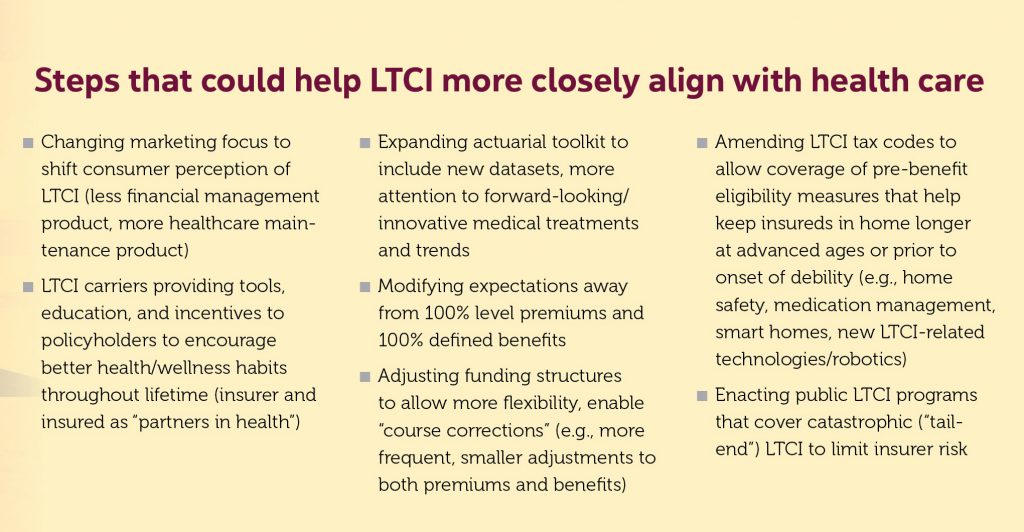

- Changing marketing focus to shift consumer perception of LTCI (less financial management product, more healthcare maintenance product)

- LTCI carriers providing tools, education, and incentives to policyholders to encourage better health/wellness habits throughout lifetime (insurer and insured as “partners in health”)

- Expanding actuarial toolkit to include new datasets, more attention to forward-looking/innovative medical treatments and trends

- Modifying expectations away from 100% level premiums and 100% defined benefits

- Adjusting funding structures to allow more flexibility, enable “course corrections” (e.g., more frequent, smaller adjustments to both premiums and benefits)

- Amending LTCI tax codes to allow coverage of pre-benefit eligibility measures that help keep insureds in home longer at advanced ages or prior to onset of debility (e.g., home safety, medication management, smart homes, new LTCI-related technologies/robotics)

- Enacting public LTCI programs that cover catastrophic (“tail-end”) LTCI to limit insurer risk

References

[1] Hybrid products are effective at managing a number of non-LTC risks, while their pricing, which relies on margin from the life product base, is stable. Nevertheless, because they are designed primarily as life insurance products, they offer less LTC benefits for the premium dollar in comparison to stand-alone policies whose sole purpose is to provide LTC benefits. Moreover, they present a host of suitability issues sellers must address. [2] Source: Statista.com. [3] The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (Scribner, 2010), pp. 37–45. Mukherjee shows that the prevalence of cancer is a consequence of longevity, which has been extended by the elimination of infectious diseases as well as aging demographics. Nineteenth-century doctors puzzled over why most people in earlier times did not get cancer, and some linked it to civilization itself. Mukherjee notes, “the link was correct, but the causality was not: civilization did not cause cancer, but by extending human life spans—civilization unveiled it” (p. 44). [4] Over time the NAIC required in its Long-Term Care Model Act and Regulation the inclusion of guaranteed renewability, so that no LTCI policyholder could be cancelled after paying premiums for years, provided the policyholder paid the amount of premium required by the insurer. More recently, the NAIC has prohibited use of the term “level premium” because some policyholders thought it meant that premiums could not be changed. It has added an injunction that reads as follows: “The term ‘level premium’ may only be used when the insurer does not have the right to change the premium” (Model Act 640-1, Model Regulation 640-1, finalized in 2017, Section 6 A (4).) [5] For a full discussion of this concept, see Paul E. Forte and Roger D. Loomis, “The Case for Variable Long-Term Care Insurance Benefits,” Contingencies, January/February 2018. [6] James F. Fries, M.D., “Aging, Natural Death, and the Compression of Morbidity,” New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 303, No. 3, July 17, 1980. [7] See Dale E. Bredesen, MD, The First Survivors of Alzheimer’s: How Patients Recovered Life and Hope in Their Own Words (Avery, 2021). Rejecting the notion that cognitive decline is just a normal part of aging, Bredesen, a UCLA professor, evaluates the neuroplasticity network, analyzing genetics, hormones, nutrients, and the “insults” that jeopardize network sufficiency, such as infection, toxins, and inflammation.