Published results on mortality experience can help lead to fair results

By Anthony H. Riccardi and Lauryn E. Stewart

For those who work as forensic actuaries, behold a gold mine of insight into the understanding of in-force settlement annuity contracts. The tabulated survey data in the Society of Actuaries’ 56-page report 2005-2017 Structured Settlement Mortality Experience Report provides us with an extensive layout of mortality experience over a 13-year period. It not only enlightens the general understanding of in-force settlement annuity contract mortality experience; it also allows us to gain specific knowledge for an otherwise imponderable—in-force mortality experience for rated contracts.

This knowledge may have a particular impact during a factoring negotiation, a topic covered in a previously published article.[1] Doing a careful page-by-page reading of the report’s actual-to-expected mortality ratios reveals important information for life-contingent contract payees seeking liquidity. Report tabulations and an applied illustration show how the mortality experience data can be a leg up in securing equity and fairness during a factoring redemption negotiation.

First, let’s restate certain concepts and operational definitions for those readers unfamiliar with terms of art in forensic actuarial work.

- Settlement Annuity: A contractually stipulated schedule of periodic benefit payments, which are due and payable to a plaintiff/annuitant (also known as a payee), not subject to personal income tax and defendant-financed from the lump-sum proceeds of either a personal injury or wrongful death settlement or award in compliance with Internal Revenue Code §104(a)(2) and Revenue Ruling 79-220. The most common benefit modes of a settlement annuity contract are:

- Annuity Certain: A stream of specified benefit payments made to an annuitant, or to his estate, at periodic intervals for a predetermined number of years (or months) only; payments are not dependent on the survival of the annuitant.

- Life Annuity: A stream of specified benefit payments made at periodic intervals over the duration of an annuitant’s lifetime; if there is a periodic payment limitation that specifies a point when the payments must otherwise cease (notwithstanding the annuitant’s survival) the benefit stream is known as a Temporary Life Annuity.

- Factoring: A liquidity transaction that converts a settlement annuity contract’s stipulated schedule of periodic payments into an immediate lump sum payable to a payee/annuitant.

Annuity Advantages

There are settlement annuity advantages inuring to the best interests of plaintiffs, defendants and, in certain circumstances, public assistance programs.

For a plaintiff:

- Investment Security: Annuity assets are part of a life company’s overall assets and thus benefit payments are comprehensively protected and regulated by state statutes,[2] which is important to a risk-averse plaintiff;

- Avoidance of a wasteful dissipation: Published data on the outcomes of lump-sum settlements and verdict awards paid to injury victims indicate a general lack of good judgment on budgeting and investment choices, which along with a lump sum inadequately managed, can be replaced by a stream of periodic payments being the key to avoiding the risk of dissipation and dependence on backup from public assistance programs; and

- Income Tax Exemption: An absence of federal, state, and local income taxes on the benefits paid to replace the plaintiff’s lost wages means that the plaintiff’s recovery of lost income is leveraged upward and, more often than not, overcompensated.

For a defendant:

In several circumstances, there are distinct annuity advantages for a defendant. Business groups and trade associations have for some time strongly lobbied for periodic payment mandates from their state legislatures. Generally, the lobbying has focused on annuity financing of large future damages verdict awards into either life or temporary life periodic payments. These life contingent benefit streams are generally designed for severe-injury case settlements, avoiding a large award that would otherwise be distributed to a plaintiff in a single lump sum.

The following simple illustration will serve to explain the value of a settlement annuity to a defendant seeking to compensate a seriously injured plaintiff for her future medical expenses and settle a tort matter in suit:

Assume an action has begun and the case has proceeded through a bifurcation hearing on liability in which the defendant(s) have been determined negligent and liable for the damages that left a 40-year-old woman severely injured and needing medical care for the next 15 to 20 years. The estimated medical care cost is $10,000 per month, increasing at 3% to 4% per annum.

Of course, a case of this nature would include a claim for the plaintiff’s future pain and suffering. Most pain and suffering awards are awarded in a lump sum, and that calculation is not addressed here. Otherwise, the following illustrates a potential defendant settlement offer, as compensation for her encumbrance of future medical expenses.

Potential Offer:

Annuity Mode: 20-year Temporary Life

Benefit Amount: $10,000 per month, increasing at 4% per annum

Cost:

Standard female 40-year-old premium: $2,796,769

Substandard female 60-year-old premium: $2,587,007

Difference $209,762

Assuming the life carrier’s medical underwriting decides to issue the 60-year-old substandard mortality rating, the defendant’s financial advantage shown here is obvious. The potential contract benefit streams are identical, with an overall potential benefit payout of $3,573,360, which is a point often stressed in the defendant’s presentation to the plaintiff. Of course, the income tax exemption also comes strongly into play, being that all settlement annuity contract benefits are uniquely exempt from income tax. This latter point is both a blessing and a curse to the plaintiff. The plaintiff receives fully tax-exempt benefits, though only because the contract falls under strict IRS regulations that prohibit the plaintiff’s transfer of the contract, per se, to a third party. This means that with her acceptance, the plaintiff—being only a payee—has no easy access to attaining contract liquidity if she becomes cash-strapped. This is often a difficult decision for a plaintiff dealing with an extremely stressful circumstance. Although the plaintiff may reject the settlement annuity altogether, the authors’ experience suggests that plaintiffs, through either advisement or prudence, are likely to consent to becoming a payee of a defendant’s settlement annuity contract. Thereafter though, depending on how the plaintiff’s circumstances evolve, getting contract liquidity means a complete reversal of her life contingent benefit stream into an immediate lump sum payment. This redemption effort generally becomes a considerable problem for the plaintiff. Enter the now popularized solution to this problem, a factoring market negotiation—“It’s your money, and you can get it now!”—and so it goes.

Factoring—Solution

Cash-strapped payees of stipulated benefits from settlement annuities can seek liquidity by initiating a redemption negotiation with a settlement annuity factoring company. The question then becomes: What is an equitable and fair lump sum redemption? It is beyond the scope of this article to either presume or speculate on the sales pitches initiated to an anxious, cash-strapped contract payee by a factoring company representative, and on the interplay of the ensuing negotiations after the factoring company’s initial redemption offer. No doubt, though, the factoring company will stress that its redemption offer must be trimmed to reflect its risk encumbrances. Two significant aspects of risk after the redemption are as follows:

- Because a payee cannot transfer contract ownership, a factoring company is only accepting the payee’s promise to have the contract benefits redirected through a third party (bank account, etc.), and thereafter those periodic benefit payments will be made payable to the factoring company. This means that the factoring transaction is conducted at arm’s length and not collateralized by the contract-issuing life company, which creates a financial default risk on the benefit stream. In the authors’ experience, this risk is important in the initial redemption offer made to the payee, though it is beyond the scope of this article.

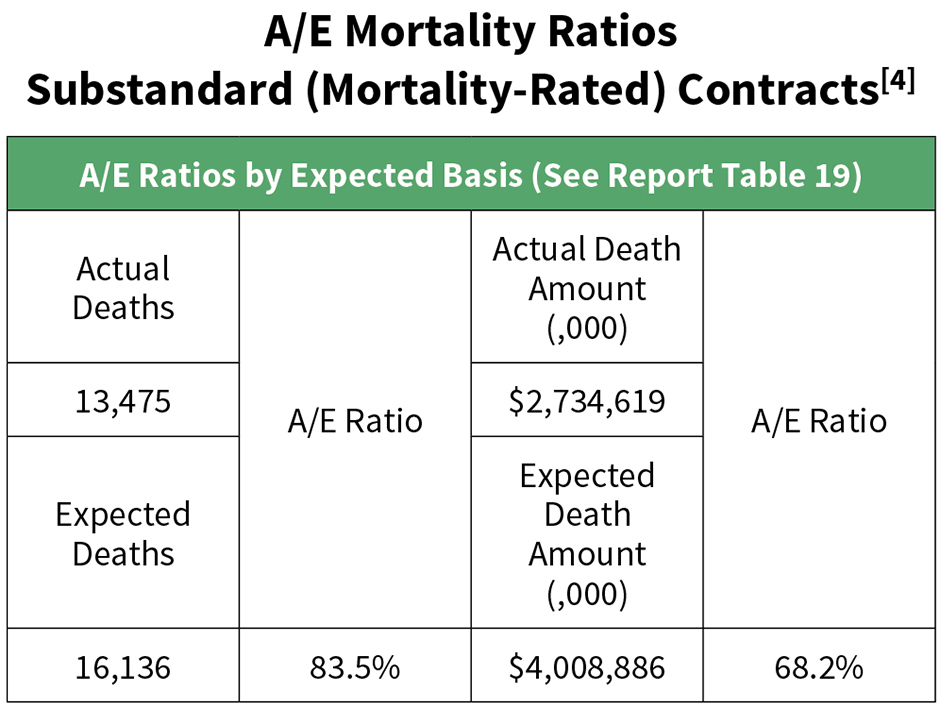

- For a contract with a sizable life-contingent benefit stream, to this point, there have been no guidelines as to whether or how much the payee’s mortality risk will impact the duration of the stream of benefit payments. This aspect of risk is particularly important for a contract written as a substandard issuance and, subsequently, put into a redemption negotiation. The redemption negotiation may wholly turn on how long the factoring company can expect a severely injured payee to survive. The point here is the potential period for which a contract’s life-contingent benefits are accurately reflective of the life company’s underwriting. This aspect of underwritten mortality risk assessment accurately is exactly within the scope of the SOA report’s calculated tabulations of the life company data, expressed as actual-to-expected (A/E) mortality ratios. Selected tables[3] of calculated payee mortality ratio A/E percentage tabulations follow.

- Overall, not represented by gender, the A/E is different when measured by the contract premiums paid, being notably lower when measured by the dollar amount of contract premium paid. The deaths A/E ratio of 83.5% shall be included in calculation.

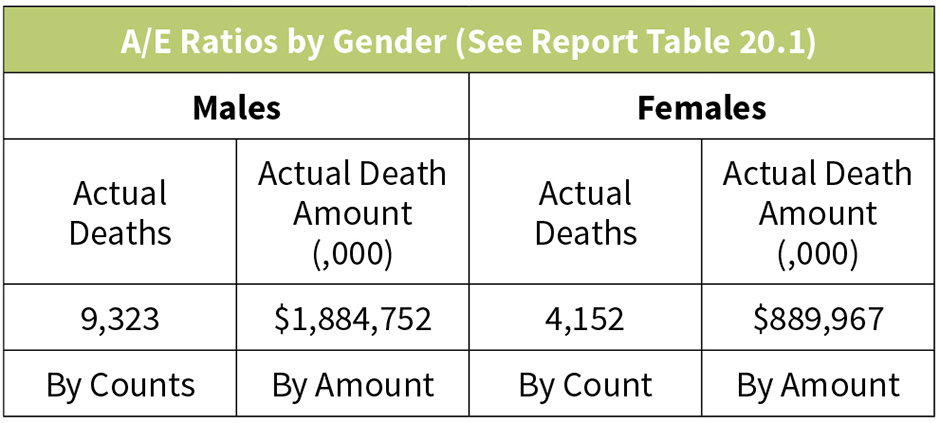

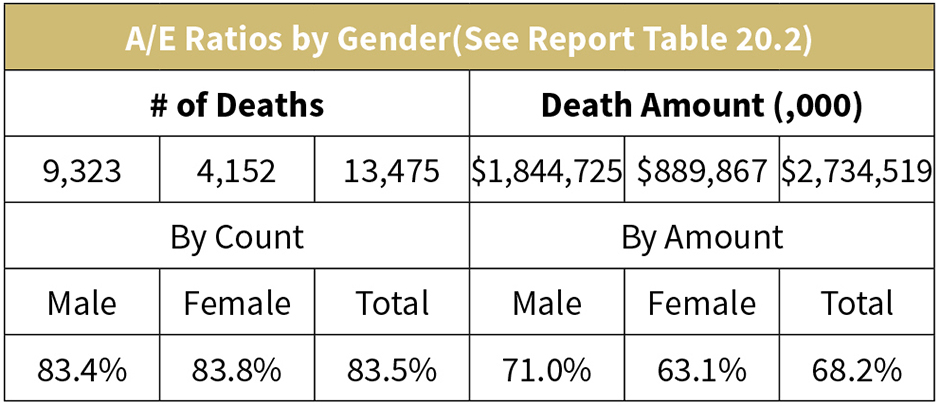

- Though the percentage male and female A/E mortality experience is virtually identical, the female contract dollar percentage is somewhat lower. This data shall be included in the illustration calculations below, representing the 63.1% A/E, for the average female actual death.

- Although the A/E experience of female and male death counts are virtually identical, the female percent death A/E is somewhat higher. The 83.8% female death A/E ratio shall be included in the illustration calculation below.

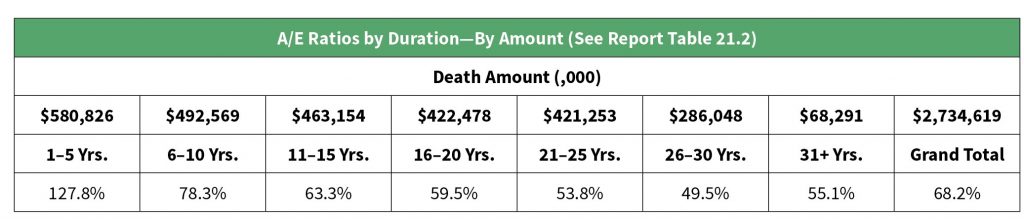

- The A/E ratio shows a substantial pattern of decline as the contract years of duration proceed above 30 years.

- The highest A/E ratio measured by duration and death is the first five years, showing 97.8%, though overall the A/E ratio experience is only 83.5%. This data shall be included in the illustration calculations below, with respect to the years 1-5 A/E, 97.8%.

- The highest A/E ratio measured by contract years and amount is in the first five years of the contract term, showing well over 100%, though overall the A/E ratio experience is only 68.2%. This data shall be included in the illustration calculations below, with respect to the 1-5 year A/E of 127.8%.

Case Illustration

Based on the above workup of a settlement for a mortalityrated 40-year-old woman who became a payee of a 20-year temporary life contract and is now seeking liquidity through factoring negotiation, the following calculations have relevance. The relevance of these calculations is limited to the interplay during a payee factoring negotiation regarding a contract that sold to a defendant for some $2,587,007 in premium, only a short time ago.

- Table 19 Calculation: $2,587,007 × (1/0.835) = $3,098,212

- Table 20.1 Calculation: $2,587,007 × (1/0.631) = $4,099,853

- Table 20.2 Calculation: $2,587,007 × (1/0.838) = $3,087,121

- Table 21.1 Calculation: $2,587,007 × (1/0.978) = $2,645,201

- Table 21.2 Calculation: $2,587,007 × (1/1.278) = $2,024,262

Five-Table—Mean Calculation = $2,990,930

The authors have observed a widely held belief that a factoring initial redemption offer will be discounted by 50% for the factoring company’s extra risk encumbrance, when compared to the redemption of a collateralized annuity contract. By applying solely this rule of thumb, an initial offer in the negotiation of cash redemption for the above newly issued contract comes to one-half of the defendant’s premium contract, $2,587,007, which equals $1,293,504.

The knowledge of the experience data, shown in the calculations of this particular illustration, gives the payee a leg up on her negotiation, allowing her a wide negotiation range—above $1,293,504, to as much as the mean A/E calculation above, $2,990,930.

The point here is providing an opportunity for equity and fairness for the payee’s effort to seek liquidity during the negotiation of a lump sum-redemption.

Concluding Remarks

The purpose of collecting research data, actuarial or otherwise, is to provide the field with knowledge to answer questions. The SOA’s data on settlement annuity mortality experience provides a broad spectrum of survey data for the field. Our application of the SOA’s survey research data was narrowly purposed. The ostensible purpose was limited to determining how well a payee’s settlement contract is medically underwritten and age-rated, being thereafter compared in terms of the payee’s actual mortality.

The data in the calculations shown in the case illustration here suggest that the expected mortality rates are substantially higher than the actual mortality rates. For a payee seeking to redeem her life contingent contract in the factoring market, this is good news. All else being equal, her negotiation in pursuit of a fair and equitable lump sum is enhanced. Understand, though, that this case illustration and analysis cannot be completely generalized, due to its limitations.

Some of the limitations to our analysis using the SOA data include the following:

- The only A/E data we featured was the Social Security table data, averaged over a 13-year period.

- After 2017—or else even prior to 2017—life companies may have begun being generally less aggressive in underwriting and rating practices.

- A disproportionately large amount of A/E ratio data may have come from only a few aggressively underwriting life companies.

Again, the importance of the SOA data is that it helps answer questions for the actuarial field, as it did for the question featured in our work.

ANTHONY H. RICCARDI, MAAA, is economist and actuary at AHR Associates. LAURYN E. STEWART is an associate at AHR Associates. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Joel Sklar, chair of Individual Annuity Committee for the Society of Actuaries.

References

[1] “The Role for Actuaries in Settlement Annuities and Factoring”; Contingencies; July/August 2015. [2] Typically a company will also transfer its settlement annuities to an “assignee” shell company to further protect the company against the risk of default during a bankruptcy proceeding. [3] The selected report tables include Table 19, 20.1, 20.2, and 21.1, each reflecting life contingent, mortality-rated payees. [4] The selected basis for life table data reflects judicial preference in New York for expert testimony based on government-sourced data and, therefore, we rely here on the A/E data from the report’s 13-year midpoint, 2011 SSA Table (2005–17 midpoint), described on page 12 of the report.