By April S. Choi, C. Jo Erwin, Kevin Geurtsen, Julia Lerche, Yi-Ling Lin, Vanessa M. Olson, Rebecca Owen, Susan Pantely, Anthony Pistilli, Chris Schmidt, Martin E. Staehlin, Sara Teppema, and Tammy Tomczyk

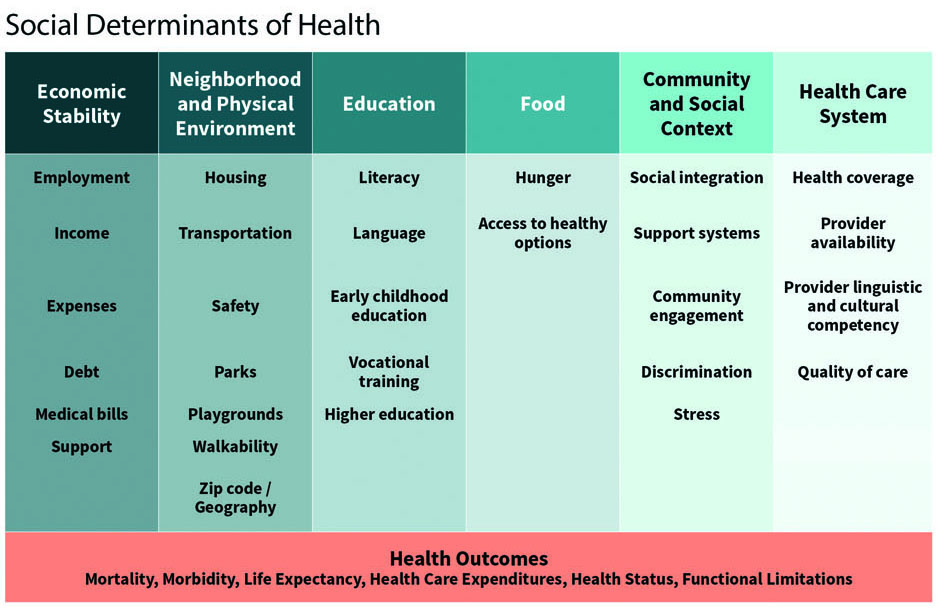

Many intrinsic characteristics contribute to our state of health, such as age, genetics, and lifestyle. However, the external conditions into which we are born, grow, live, and work, known as social determinants of health (SDOH), also have a large impact on our health. Research suggests that 30% to 50% of health outcomes are attributable to SDOH, while only 10% to 20% are attributable to medical care.[1, 2]

Given this suggested strong correlation between SDOH and health outcomes and the increased emphasis on value-based health care, policymakers and the health care community have begun to incorporate SDOH initiatives into providers’ health care practice and payment models, with the goal of improving health outcomes.

The purpose of this article is to broaden actuaries’ and others’ knowledge of the emerging field of SDOH in order that we may bring an outcomes-based, financial acumen to the study of SDOH. This article will review major categories of SDOH; stakeholders; current initiatives; regulatory considerations; data and measurement; financial considerations; and future needs.

A Broad Range of External Conditions Affect Our Health

In assessing the impact of SDOH on a population, it is helpful to consider the following:

- Economic Conditions. Does the population experience unstable employment, income, or other financial insecurity?

- Neighborhood, Physical Environment, and Housing. Does the population have access to safe housing, transportation, and green spaces?

- Education. Does the population have access to stable schools for children? Is the population literate—as well as health-literate?

- Food, Water, and Air. Does the population have easy access to nutritious food and clean drinking water? Is the community exposed to air pollution?

- Community and Connection. Does the population have access to good community support systems? Is the population at high risk of discrimination, noise, or stress? Is there a social support network for individuals who live alone?

- Violence and Trauma. Does the population have high Adverse Childhood Experience[3] scores? Is there a high rate of violence at home, or gun violence in the neighborhood?

- Health Care. Does the population have adequate access to health care? Are there language or cultural differences creating barriers to timely, effective care?

Stakeholders Need to Work Together

Many experts agree that improving population health[4] requires that upstream efforts be directed at building healthier communities that address the environment, housing, transportation, access to healthy food, and safe spaces, as well as downstream efforts that address an individual patient’s health care and social needs. Stakeholders including regulatory and government bodies, community-based organizations, nonprofit organizations, payers, health care providers, and individuals, can all work together to achieve successful results.

Regulatory and Government Bodies

Public health agencies play a lead role in recommending polices, proposing regulations, implementing education programs, conducting research, and supporting partnerships to assure we live in healthy communities. Federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)[5] have implemented a wide range of interventions and strategies such as tobacco control, safe routes to school, water fluoridation, and early childhood education.

State, county, and city agencies play a significant role in supporting local SDOH programs, such as homelessness, safe neighborhoods, water, housing, etc.

Nonprofit Organizations

Many nonprofit organizations such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF)[6] and the Kaiser Family Foundation[7] conduct research on SDOH topics. Their publications, webinars, and conferences serve as a good source for up-to-date learning resources on SDOH initiatives.

Other organizations such as the National Alliance to Impact the Social Determinants of Health (NASDOH)[8] and Aligning for Health (AFH)[9] are comprised of groups of stakeholders that advocate for the importance of addressing social needs as part of an overall approach to health improvement.

Payers

As health care costs continue to rise, health care payers including Medicare, Medicaid, commercial insurers, and self-insured employers, continue to seek ways to slow the cost growth and improve health outcomes. Payers are experimenting with payment models and programs to address social needs. They assess the associated cost/benefit trade-offs. One of many considerations is weighing the near-term cost versus the long-term benefit. For example, could the cost of subsidizing access to fresh food be justified by reducing the prevalence of diabetes in the long term?

Community-Based Organizations

Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) have deep community roots and established relationships with various community resources. They provide a wide range of social supports such as transportation, nutrition and services for the homeless,[10] often for a small segment of a local population. CBOs such as area agencies on aging (AAAs) and centers for independent living (CILs) have been serving the health-related social needs of the elderly for decades.

Health Care Providers

With the increasing shift to value-based payment models, providers are assuming greater financial accountability for health outcomes. Hospitals and physicians are recognizing the need to address patients’ social needs. For example, care management that includes focus on transportation can help reduce emergency department visits, unnecessary hospital admissions, and readmissions.

Increasingly, health care providers are partnering with CBOs to more effectively address their patients’ complex medical and social needs by integrating their complementary expertise.

Individuals

Perhaps the most critical stakeholders are the individuals who may have significant health issues in addition to financial constraints, unsafe neighborhoods, food insecurity, or other social risk factors and needs.

Sharing Current Initiative Learnings Can Guide Future Program Implementations

Recognizing the importance of SDOH, both the public and private sectors are promoting and directing efforts to address SDOH. Because the majority of the United States population is covered by one of the largest three payers—employers (49%), Medicaid (20%), and Medicare (14%)[11]—coordinated research and shared learning resources that include these payers will translate to more rapid implementation of initiatives.

Medicaid

To date, most of the health care system’s SDOH initiatives have been targeted toward the Medicaid population. In order to contain health care costs and improve outcomes, Medicaid programs are increasingly considering how to address SDOH for a broader population, beyond the high-need enrollees. The RWJF explored the next-generation practices that states are currently deploying to address the social factors using Medicaid 1115 waivers and managed care contracts, as well as specific steps states can take to implement these practices.[12] The next-generation practices include:

- Moving beyond screenings to systematic efforts to connect enrollees to social supports, including tracking outcomes after referral to a social services provider;

- Expanding the scope of interventions beyond high-need populations to include children, families, and healthy adults;

- Addressing harder-to-tackle social issues such as providing care to socially isolated or formerly incarcerated individuals;

- Building a stronger network of community-based organizations with health care providers;

- Aligning financial incentives to support interventions such as requiring value-based payments as part of provider reimbursements, and linking withhold payments to SDOH-related outcomes;

- Creating opportunities for affordable housing, such as requiring in-house expertise on housing; and

- Systematically evaluating SDOH interventions through pilot programs.

Even without direct Medicaid financing, Medicaid managed care plans have invested in innovative programs they believe will deliver better care while reducing costs. For example, a United Healthcare (UHC) Medicaid program provides housing to identified members[13] as a UHC business venture. A key component of the program is the committee of physicians who invite selected members into the program. The committee sets restrictive standards: a minimum of $50,000 in prior-year claim costs, an in-depth review of clinical complexity and persistency of conditions, and a projection of when a member may be prepared to graduate from the subsidized housing program. The program is targeting 10 apartments in each new city where it implements the program.

Medicare

Medicare is also undertaking initiatives to heighten recognition of SDOH. Current programs to address health-related social needs include:

- Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model: The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s (CMMI’s) AHC Model[14] will support local communities to address the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries by bridging the gap between clinical and community service providers.

- Medicare Advantage Supplemental Benefits: Starting in 2020, Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have greater flexibility to offer chronically ill beneficiaries’ nonmedical benefits (also see the “Federal Regulations” section below.)

Employers

Employers are also exploring SDOH activities. More and more employers have indicated strong interest in addressing the social conditions that affect employees’ health and well-being. For the 2020 plan year, the National Business Group on Health (NBGH) survey of large employers showed they would consider the following as part of the health and well-being strategy:[15]

- 90% would include financial/economic issues

- 84% would include health care access/literacy

- 34% would include food quality and access

Providers

Health care providers are increasingly engaged in integrating SDOH initiatives into care delivery practices and systems. Various examples include the following:[16, 17]

- Mount Sinai, a New York health system, used artificial intelligence to help unlock social determinants data in its electronic health records (EHR) through unstructured notes;

- Montefiore, another New York health system, has achieved savings by investing in housing for homeless patients, dramatically lowering its emergency department visits and unnecessary hospitalizations; and

- CVS Health will direct selected Aetna Medicaid and dual-eligible members to access social services within its community by utilizing UniteUs’ aggregated network of social care providers.

Health Care Technology Companies

SDOH initiatives are also stimulating health tech startups[18] such as Solera, UniteUs and CityBlock Health. Utilizing technology platforms, the initial focus is on directing patients to social services and public health resources more appropriately and easily. The next phases are to standardize data collection; use artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to identify patients; analyze outcomes; and evaluate the return on investments.

Regulations Play A Major Role

Whether designing a SDOH program for Medicare, Medicaid, or commercial markets, federal and state-level regulations play a major role in developing a viable program.

Federal Regulations

In recent years, enacted regulations have provided additional focus on SDOH:

- Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act. The 2014 IMPACT Act requires the reporting of standardized patient assessment data with regard to quality measures and standardized patient assessment data elements (SPADEs). In 2019, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued rules for plan year 2020 incorporating new SPADEs for social risk factors—race, ethnicity, preferred language, interpreter services, health literacy, transportation, and social isolation.[19, 20, 21, 22]

- Medicare Advantage Benefits. With the passage of the Creating High-Quality Results and Outcomes Necessary to Improve Choice (CHRONIC) Care Act in 2018, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced two new types of benefits for plan year 2020:

- The Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill (SSBCI) program allows MA organizations to provide supplemental benefits that are non-primarily health related and/or offered non-uniformly to eligible chronically ill enrollees. Specifically mentioned are “benefits to address social needs,” as well as transportation for nonmedical needs.[23]

- CMMI announced a Request for Applications for a new Value-Based Insurance Design (VBID) model that will test the impact that targeted benefit design based solely on socioeconomic status, as defined by low-income subsidy status, has on the overall cost and quality of care.[24]

Federal and State Regulations in Medicaid

Medicaid programs reflect a mix of both federal and state-level controls, which creates a tremendous variance in what may be possible within each state. For example, the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) rules for Medicaid managed care plans provide states flexibility in allowing SDOH costs to be considered the same as other medical costs for purposes of allowable MLR levels. States can also incorporate SDOH concepts into their care coordination and case management programs, by covering the administrative costs of linking members to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and other non-Medicaid funded programs. Other CMS waivers have enabled pilot programs for food and housing security, transportation, and interpersonal safety.

Regulatory Constraints

On the other hand, new SDOH programs must work within the constraints of current frameworks, which may limit what can be done, either intentionally or unintentionally. Examples of barriers that can preclude the effectiveness of programs include:

- While Medicaid managed care plans have the flexibility to cover nontraditional services (such as nutrition services or home-delivered meals) outside of their contractual requirements with state Medicaid programs, capitation rate setting rules for Medicaid managed care prohibit the inclusion of such services unless they are demonstrated to be a cost-effective alternative to an otherwise contractually covered service.

- Medicaid managed care capitation rate setting rules and approaches also present barriers in aligning incentives for investments in services that address social determinants with the accrual of savings. If a health plan’s investment in nontraditional services leads to reduced expenditures in contractually required covered services, those savings typically accrue to states through future decreases in capitation rates, preventing the plan from fully realizing the benefits of their investments.

Standardized Data and Measurement Can Expedite Program Deployment

Data and measurement of both the existence of SDOH within a population, and the effects of interventions, are essential tools for stakeholders in order to deploy SDOH initiatives effectively and efficiently.

Identification of Target Population and Individuals Through Screening Tools

Identifying a specific population or individual and determining their social needs is an important first step. Providers are using screening tools to better understand the socioeconomic drivers of their patients’ health status. Once the needs are identified, patients can be referred to community resources, and progress is tracked to ensure resolution of the needs. Shown below are a few examples of the tools:

- The Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) Screening Tool, was developed for CMMI to use in the AHC Model.[25, 26] It screens for a patient’s social needs in five core domains and eight supplemental domains.

- Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE)[27] was developed by the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). It consists of 16 national core measures as well as four optional measures.

- North Carolina Medicaid Managed Care Standardized SDOH Screening Questions[28, 29] was developed by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS). The tool screens for four priority domains and 13 optional domains.

There are many other screening tools, but there is not yet a standard tool or a standard set of domains. In order to address population health and SDOH more broadly, a standardized set of domains and screening questions would further enable common measurement across populations and among all stakeholders.

Public Data

There are many public resources and datasets that can be helpful in identification and measurement of SDOH. Some of these include the large repositories of census data, climate data, local and national public health trackers, and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data tools.

The CDC compiled a list of its most indicative data[30] for SDOH. It includes:

- Chronic Disease Indicators is an interactive data set that looks at state-specific measures of chronic disease and health-related behaviors.

- Interactive Atlas of Heart Disease and Stroke is an interactive data set that provides health risk factors and SDOH risk factors at the county level, for a number of cardiovascular conditions.

- Environmental Public Health Tracking Network is an interactive data set that provides characteristics of environmental quality by county such as air, drinking water, or heat stress illness; as well as aspects of each, such as ozone levels or nitrate levels.

- The Social Vulnerability Index is a downloadable data set at the census tract level that uses 15 census variables, such as poverty and insurance status, to create an index to estimate the vulnerability of a population to hazardous events or natural disaster.

- Vulnerable Populations Footprint was created by Center for Applied Research and Engagement Systems (CARES) and uses a location to return relative measures of vulnerability, such as poverty and education.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also offers data sources, tools as well as research grants to assess SDOH impact and to address social needs.

The RWJF and the University of Wisconsin Institute for Population Health have collaborated on the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps (CHR&R)[31] program since 2010. Each year, the program provides a revealing snapshot of how health is influenced by where individuals live, learn, work, and play. The 2019 rankings focused on the critical role housing has on the health of individuals and communities.

Other public data sources include the livability index from AARP and the Metro Monitor from Brookings Institution.

Administrative and Claims Data

Claims and eligibility data housed by health insurers and employers, can be very useful in finding and tracking members with social needs. Certain ICD-10-CM codes housed in the claims data such as those for domestic violence, and ICD-10-CM codes included in categories Z55-Z65 (“Z codes”) can be used to identify members’ social risk factors. Z codes have not yet been widely used, but the American Hospital Association[32] has encouraged hospitals to use them on a more consistent basis.

Member addresses found in eligibility data could be combined with information from other data sources (subject to privacy or other legal requirements) to learn about the neighborhood members reside in. And, frequent address changes can indicate housing instability.

Clinical Data

Individual patient information such as medical procedures, diagnosis, and prescriptions can either be harvested from clinical notes or obtained from electronic health records (EHR). When clinical data is combined with SDOH data, rich longitudinal profiles of patients’ data can be developed.

Standardizing Data and Collection

With the advent of many of these initiatives to address social factors, it becomes apparent there is a need to standardize data and its collection. There are several nationwide initiatives that seek to improve interoperability and data sharing between health care and social care, through standardization of data and terminology,[33] development of comprehensive data repositories, and incorporation of technology. Two examples are as follows:

- The American Medical Association and United Healthcare teamed up to improve the process of incorporating SDOH into clinical care, by supporting the creation of 23 new ICD-10 codes related to social determinants.

- The Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network (SIREN) at the University of California, San Francisco is leading the Gravity Project.[34] This project will identify a set of common SDOH data elements and their associated value used for screening, diagnosing, treating, and planning in a patient’s EHR. The goal is to enable easier electronic data sharing. It will focus initially on three social domains: transportation, food insecurity, and housing instability and quality.

Cost-Effective Programs Are Essential, So Is Flexible/Sustainable Funding

Appropriate containment of medical costs is an important benefit of health care initiatives focused on addressing gaps in SDOH, and the long-term financial viability of those initiatives often requires a reasonable balance between medical cost savings and operating costs. This type of analysis can be complex and present a number of counterintuitive dynamics. For example, successfully addressing social determinants may not produce improved clinical outcomes, and improved clinical outcomes may not correlate with medical cost savings. In addition, other confounders such as the Hawthorne Effect, in which the behavior of study subjects changes because they are being observed, may produce the illusion of cost savings.

The UHC housing program outlined in the “Initiatives” section has implemented its strict criteria, and limited its scope in order to produce the medical cost savings necessary to offset the program’s operational costs. Joseph Gaudio, UHC’s market CEO for Arizona, said in an interview about the program, “The reality is, to truly scale this, addressing the needs of social determinants at some point, we will need more public support.”

Health systems are also experiencing funding shortages needed to scale SDOH initiatives. A 2017 Deloitte Center for Health Solutions survey of 300 hospitals and health systems[35] found that 80% are “committed to establishing and developing processes to systematically address social needs as part of clinical care” yet also noted that “gaps remain in connecting initiatives that improve health outcomes or reduce costs.” Additionally, “about one-third (35 percent) of hospitals are tracking cost outcomes from their social needs investments,” and “most hospitals do not have dedicated funds for all the populations they want to target (72 percent), and report that finding sustainable funding to address social needs is a challenge.”

Broad system integration may be a principal means toward overcoming these challenges. A WellCare Health Plan program focused on connecting patients to existing services that meet their social needs found an 11% reduction in spending among members who reported that their social services needs were met, and only a 1% reduction in costs for members who reported their social services needs were not met.[36] Partnering with existing social services agencies has been demonstrated as one way for payers and providers to cost-effectively scale their programs, while the social services programs may benefit from increased access to populations most in need of assistance.

Explore Future Changes That May Spur Program Growth

Recognizing the importance of SDOH programs and the positive impact they can have on health outcomes, some public health policy discussions are now focused on what needs to change in order for SDOH programs to flourish and grow. Some of these leading ideas are discussed below. The list was mainly drawn from the report Leveraging Data on the Social Determinants of Health[37] prepared jointly by the Code for Open Data Enterprise and HHS’s office of the Chief Technology Officer, and the book Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health,[38] published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Define, Standardize, Collect and Integrate Data

- Having clear definitions[39] of SDOH, social risks, and social needs, and which SDOH categories are under consideration, is essential. Clear definitions would facilitate communications and bring clarity of the roles each stakeholder plays in either addressing the community’s social conditions, identifying the social risk factors that a community or individuals face, or mitigating individuals’ social needs.

- Adopting data standards and definitions and identifying common data elements and their associated values would set a strong foundation for data collection, aggregation, integration, and sharing.

- Requiring or strongly encouraging broader adoption of existing data, such as the use of ICD-10-CM “Z codes,” would be a good step toward quantifying SDOH needs.

Standardize Measures and Develop an Open System of Infrastructure, Analytics, and Applications

- Implementing an open SDOH data ecosystem would streamline the patient care process; allow providers to focus on delivering medical and social care; and enable machine learning and more advance applications in measurement, benchmarking and predictive analysis.

- Using a common, structured, and interoperable system that screens patients’ social needs, tracks referrals and outcomes, and monitors care management progress on a centralized repository is a good example of how an open system could enable better care coordination.

Collaborative Efforts Create Better Outcome Measures

Measuring the impact of social factors and the effectiveness of interventions on health is complex. Considerations include:

- investments in the near term may yield benefits many years later;

- spending by one sector may yield benefits by another sector; and

- separation of the impact of an individual social factor versus the interactions of multiple social factors.

Despite these complexities, it is essential that stakeholders collaborate to more rapidly develop a systematic approach to measure the impact on health improvements, functional status, or quality of care. Measured results would enable stakeholders to make informed policy decisions, guide implementation of best practices, and prioritize resources appropriately.

Blend or Braid Funding Across Federal and State Programs

Funding from government sources is often siloed, with rules preventing grantees from combining funding streams across programs and often with varying reporting rules for how the money is used and tracked. While it is important to have controls on government funding, more flexible rules—such as those that allow a grantee to blend funds across programs and treat the whole person (and whole community)—would create more efficient programs.

Update Regulations and Policies

- Incorporating social risk factors assessment and benefits into Medicare and Medicaid payments from CMS and states, when there is sufficient cost-effectiveness demonstration, would facilitate the integration of social care into health care. For example:

- Incorporating social risk factors in risk adjustment methodology

- Tying quality payments to screening for social needs measures

- Allowing certain social needs benefits as expanded benefits for Medicaid, and accounting the costs similar to other medical expenses

- Updating the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy rule to promote coordinated, value-based health care by enabling sharing of Protected Health Information between health care organizations and social services agencies, without losing patient privacy protection.

Conclusion

As noted by HHS in its Healthy People 2030 framework,[40] in the past several decades, significant progress has been made in many areas such as reducing infant and maternal mortality; reducing risk factors of tobacco smoking, hypertension and elevated cholesterol; and increasing childhood vaccinations. However, the United States lags behind other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries on key measures of health and well-being, such as life expectancy, infant mortality, and obesity, while health care expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product is the highest. There is a growing urgency to look beyond medical treatments and address the social conditions that affect population health.

To make groundbreaking progress, more research and evidence are needed to demonstrate what, when, and how SDOH interventions can be cost-effective. There are many other challenges[41] to overcome, such as broadening education of SDOH to communities; changing funding structures and maximizing funding flexibility; breaking down workstream complexities; bringing additional ingenuity into medical care payment models; and building incentives to encourage individual and system changes. It also requires leadership in all areas—policymaking, governmental bodies, nonprofit organizations, health care providers, insurers, community organizations, and the technology industry—to work together in order to move SDOH interventions into the mainstream of improving individual and population health.

While this article has focused mainly on the interventions that address individuals’ social needs, it is important to recognize that in order to improve population health and successfully address both the causes and symptoms of health impairment, upstream public health efforts directed at improving the social conditions need to be in the forefront as well. Medicalizing social needs is not sufficient and the health care system cannot do it alone.

April S Choi, MAAA, FSA; C. Jo Erwin, MAAA, FSA; Kevin Geurtsen, MAAA, FSA; Julia Lerche, MAAA, FSA, MSPH; Yi-Ling Lin, MAAA, FSA, FCA; Vanessa M. Olson, MAAA, FSA; Rebecca Owen, MAAA, FSA; Susan Pantely, MAAA, FSA; Anthony Pistilli, MAAA, FSA, CERA; Chris Schmidt, MAAA, FSA; Martin E. Staehlin, MAAA, FSA; Sara Teppema, MAAA, FSA, FCA; and Tammy Tomczyk, MAAA, FSA, FCA are members of the Academy’s Social Determinants of Health Work Group.

References

[1] “2015 County Health Rankings Key Findings Report.” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2015, https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/media/document/resources/CHR%26R%202015%20Key%20Findings.pdf [2] McGinnis et al. “The Case For More Active Policy Attention To Health Promotion” Health Affairs, 1 March 2002, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78 [3] “Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/index.html [4] DeSalvo K, & Harris A. “Bending the Trends.” Ann Fam Med, July 2017, http://www.annfammed.org/content/15/4/304. [5] “Health Impact in 5 years.“ United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/policy/hst/hi5/ [6] General information on the Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www. https://kff.org/ [7] General information on the National Alliance to Impact the Social Determinants of Health (NASDOH). National Alliance to impact the Social Determinants of Health, http://www.nasdoh.org/ [8] General Information on the Aligning for Health. Aligning for Health, http://aligningforhealth.org/who-we-are/ [9] General Information on the Aligning for Health. Aligning for Health, http://alignforhealth.org/who-we-are/ [10] Spencer A. “Supporting Health Care and Community-Based-Organization Partnerships to Address Social Determinants of Health.” Center for Health Care Strategies, March 2019, https://www.gih.org/views-from-the-field/supporting-health-care-and-community-based-organization-partnerships-to-address-social-determinants-of-health/ [11] “Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population.” State Health Facts 2018, Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population [12] Boozang, P., Nabet, B., & Guyer, J. “Emerging Trends for Addressing Social Factors in Medicaid.” Manatt, Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP, 12 April 2019, https://www.manatt.com/Insights/White-Papers/2019/Emerging-Trends-for-Addressing-Social-Factors-in-M [13] Tozzi, John. “America’s Largest Health Insurer is Giving Apartments to Homeless People.” Bloomberg Businessweek, 5 November 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-11-05/unitedhealth-s-myconnections-houses-the-homeless-through-medicaid [14] Accountable Health Communities Model. United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm/ [15] Thomas, Sarah. “Large Employers Are On Board with Social Determinants of Health and Virtual Care Strategies.” Health Forward Blog, Deloitte, 27 August 2019, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/blog/health-care-blog/2019/health-care-current-august27-2019.html [16] Miliard, Mike. “In 2019, Social Determinants of Health Got the Attention They Deserve.” Global Edition Population Health, Health care IT News, 23 December 2019, https://www.health careitnews.com/news/2019-social-determinants-health-got-attention-they-deserve [17] “CVS Health Announces “Destination: Health,” a New Platform Addressing Social Determinants of Health.” CVS Health News, CVS Health, 24 July 2019, https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/cvs-health-announces-destination-health-new-platform-addressing-social [18] Siwicki, Bill. “How SDOH will influence the next wave of health tech startups.” Global Edition Population Health, Health care IT News, 30 September 2019, https://www.health careitnews.com/news/how-sdoh-will-influence-next-wave-health-tech-startups [19] Medicare Program; Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities; Updates to the Quality Reporting Program and Value-Based Purchasing Program for Federal Fiscal Year 2020, 84 FR 38728 (August 7, 2019), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/08/07/2019-16485/medicare-program-prospective-payment-system-and-consolidated-billing-for-skilled-nursing-facilities [20] Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF) Prospective Payment System for Federal Fiscal Year 2020 and Updates to the IRF Quality Reporting Program, 84 FR 39054 (August 8, 2019), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/08/08/2019-16603/medicare-program-inpatient-rehabilitation-facility-irf-prospective-payment-system-for-federal-fiscal [21] Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF) Prospective Payment System for Federal Fiscal Year 2020 and Updates to the IRF Quality Reporting Program, 84 FR 39054 (August 8, 2019), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/08/08/2019-16603/medicare-program-inpatient-rehabilitation-facility-irf-prospective-payment-system-for-federal-fiscal [22] Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2020 Home Health Prospective Payment System Rate Update; Home Health Value-Based Purchasing Model; Home Health Quality Reporting Requirements; and Home Infusion Therapy Requirements, 84 FR 60478 (November 8, 2019), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/08/2019-24026/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-cy-2020-home-health-prospective-payment-system-rate-update-home [23] “Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2020 Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and Medicare Advantage and Part D Payment Policies and Final Call Letter.” Medicare Advantage Rates & Statistics, United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 1 April 2019, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2020.pdf [24] General Information on MA VBID Model. Innovation Models, United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/VBID [25] “The Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool.” Accountable Health Communities Model, United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/worksheets/ahcm-screeningtool.pdf [26] Accountable Health Communities Model, United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm/ [27] Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE), National Association of Community Health Centers, http://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare/ [28] Screening Questions, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/screening-questions [29] “Using Standardized Social Determinants of Health Screening Questions to Identify and Assist Patients with UnmetHealth-related Resource Needs in North Carolina.” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, 5 April 2018, https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/documents/SDOH-Screening-Tool_Paper_FINAL_20180405.pdf [30] “Sources for Data on Social Determinants of Health.” Social Determinants of Health: Know What Affects Health, United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/data/index.htm [31] County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, https://www.rwjf.org/en/how-we-work/grants-explorer/featured-programs/county-health-ranking-roadmap.html [32] “ICD-10-CM Coding for Social Determinants of Health.” American Hospital Association, November 2019, https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-04/value-initiative-icd-1 0-code-social-determinants-of-health.pdf [33] “Roundtable Report on Leveraging Data on the Social Determinants of Health.” United States, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Open Data Enterprise, December 2019, http://reports.opendataenterprise.org/Leveraging-Data-on-SDOH-Summary-Report-FINAL.pdf [34] “The Gravity Project: A Social Determinants of Health Coding Collaborative Project Charter.” Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network (SIREN), University of California, San Francisco, 14 March 2019, https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/sites/sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/files/wysiwyg/Gravity-Project-Charter.pdf [35] Lee, J. & Korba, C., “Social determinants of health: How are hospitals and health systems investing in and addressing social needs?” Deloitte Center for Health Solutions, 2017 https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/us-lshc-addressing-social-determinants-of-health.pdf [36] Kent, Jessica. “Costs Fell by 11% When Payer Addressed Social Determinants of Health.” HealthITAnalytics, 5 June 2018, https://healthitanalytics.com/news/costs-fell-by-11-when-payer-addressed-social-determinants-of-health [37] “Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health.” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 25 September 2019, http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2019/integrating-social-care-into-the-delivery-of-health-care [38] “Leveraging Data on the Social Determinants of Health.” Center for Open Data Enterprise, December 2019, http://reports.opendataenterprise.org/Leveraging-Data-on-SDOH-Summary-Report-FINAL.pdf [39] Green K, &, Zook, M. “When Talking about Social Determinants, Precision Matters.” Health Affairs Blog, 29 October 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191025.776011/full/ [40] https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/Development-Healthy-People-2030/Framework [41] DeSalvo K, & Harris A. “Bending the Trends.” Ann Fam Med, July 2017, http://www.annfammed.org/content/15/4/304.