The author is a member of the Academy’s Health Practice International Committee.

By Mitchell Momanyi

This article takes a comparative look at the issues of patient access, quality of care, and innovation in various regions of the world. In particular it discusses how countries’ health care systems address cost-effectiveness of care, quality of care, limiting patient financial liability, reduction of health inequities, and the use of innovations (particularly electronic health records [EHRs]). Observing how different health care systems around the globe address issues related to these factors allows for a multidimensional perspective on value, taking into account the major actors in the systems (patients, providers, health insurers and the government).

The regions chosen for discussion were Australia, China, France and the United Kingdom. While this is admittedly a limited list of countries, it represents a range of experiences with respect to political and legal institutions, funding of health care systems and delivery of health care services.

Australia

Australia has a health care system (“Medicare”) based on universal access to health care for its citizens and permanent residents. The country’s federal government plays a key role in determining the services that are covered under this system as well as other parameters such as measuring provider quality and setting provider payment rates. In some of the key health care sectors including the funding of prescription drugs and inpatient services, the federal government has laid out an agenda based on efficiency.

An example of the direct role of government in gauging the value of services can be seen in the federally subsidized Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), through which patients obtain access to prescription drugs. For drugs to be covered under this scheme, they need to undergo a check for cost-effectiveness by an independent body known as the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). The mandate to verify cost-effectiveness should not be taken for granted, as equivalent bodies in other countries (notably, the Food and Drug Administration in the United States) are only permitted to investigate therapeutic/clinical effectiveness.

In order to further shield patients from incurring exorbitant costs, the country’s Medicare system employs a range of safety nets. Examples of these are the “Original Medicare Safety Net” which covers 100% of hospital costs above an out-of-pocket threshold of AUD 477.90 (USD 334.68).[1] The “Extended Medicare Safety Net” covers 80% of the costs above an annual threshold of AUD $692.20 (USD 484.83) for low-income and senior citizens.

Underlying practices such as checks for cost-effectiveness and applying patient cost-sharing thresholds are the implicit acknowledgement that patients have a right not to be financially impoverished from high-cost treatment[2] and also the acknowledgement that health care resources (like other economic goods) are limited and therefore should be allocated in an efficient way that benefits society at large.

Provider incentives also play a role within the Australian health care system to ensure the provision of high-value care to patients. The federal government provides incentives to encourage better access to after-hours care. It also provides an after-hours advice and support line. While payments to physicians are predominantly fee-for-service, hospitals are funded by states using diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). Importantly, federal funding of public hospitals is tied to the “efficient price of services” determined by the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (IHPA).[3] The following general steps are followed in determining this efficient price:

- Care is classified into broad service categories: acute care admissions; mental health admissions; emergency care admissions and non-admitted care;

- The national classified data is then analyzed to derive the overall costs for a specific episode of care. The credibility of data is accounted for by comparing a specific episode of care to the corresponding national average and excluding episodes that would be considered as outliers. For example, for acute care admissions, episodes of care that are less than one-third or more than three times the average length of stay for a particular DRG are counted as outliers.

- Various adjustments are then applied to account for specific high-cost services and populations. These include: pediatric adjustments, specialist psychiatric adjustments, indigenous and patient remoteness adjustments and radiotherapy and dialysis adjustments.

The IHPA states that the two key objectives of the efficient price process are to determine the optimal resources to be allocated to public hospitals and to provide a benchmark for the efficient costs of providing hospital services.

The Australian health care system uses the following institutions to regulate quality of care:

- The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. This agency develops standards for the delivery of services as well as patient satisfaction.

- The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards. It is responsible for the accreditation of health care facilities.

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. It is responsible for the accreditation of GPs.

- The National Health Performance Authority. It compares and reports on the performance of a variety of providers.

The country’s health care system is notable for its transparency on measuring and publicly reporting on the performance of providers. However the degree to which provider payments are linked to quality measures is limited.

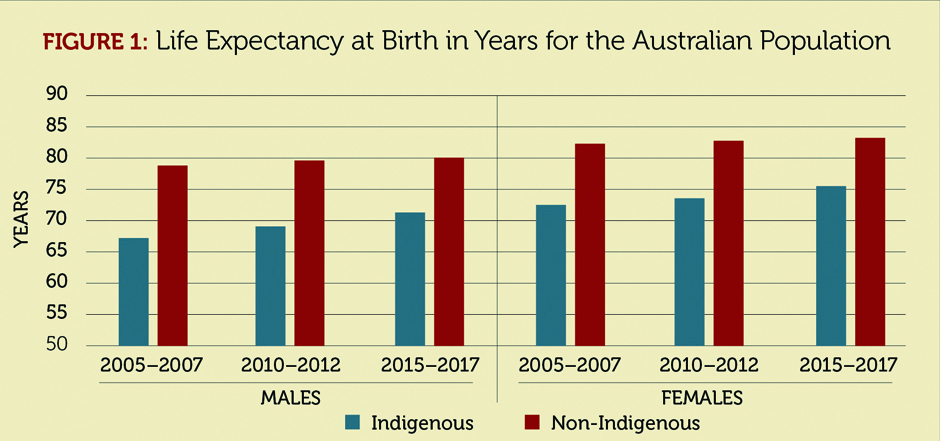

Australia has identified two areas in which significant health care inequities exist.[4] The first is the disparity in life expectancy between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (indigenous) population on the one hand and the rest of the Australian population on the other (Figure 1).

As seen from Figure 1, the life expectancy at birth for the indigenous population has been anywhere between 8 years and 11 years less than that of the rest of Australia. The second disparity in health outcomes is that between rural and urban populations. These disparities overlap because much of the indigenous population lives in rural areas. The federal government provides incentives to encourage physicians to practice in underserved areas. It also uses the Public Health Information Development Unit to track disparities such as these. While these initiatives are laudable, health care inequities among the indigenous population remain a major challenge to the country’s health care system.

China

China introduced comprehensive reform to its health system in 2009 with the aim of making access universal. It relies on a tiered system in which some providers operate at the local or town level in the rural areas and at the metropolitan or district level in urban areas. The system relies on a mix of national and local authorities to regulate quality of care, set provider payment rates, and build care guidelines.

While the goal of increasing access to health insurance coverage has been largely successful, with about 95% of the population having access to health insurance,[5] out-of-pocket cost burdens on many households continue to be a challenge on the health care system. There are no regulations that set maximum thresholds on patients’ out-of-pocket expenditures. However, some relief is provided for low-income patients through assistance programs administered by local authorities. Also, provider payment schedules stipulating the maximum that can be charged for publically financed health care services are set by the Bureaus of Commodity Prices as well as local health authorities.

The Chinese health care system uses the following institutions to regulate quality of services provided:

- The National Medical Products Administration (NMPM). The agency is responsible for the approval of new prescription drugs. However, unlike the Australian case discussed above and similar to the United States in some respects, the NMPM does not assess the cost-effectiveness of technologies and treatments.

- The Department of Health Care Quality. It is responsible for the regulation of quality of care at the national level.

- Local health authorities. They are responsible for accrediting hospitals that operate within the authorities’ jurisdiction.

- While there are national rankings of hospitals published by some third parties, information about the performance of individual physicians and practices is not available.

The country has managed to reduce some inequities in access to health care services through its reform of the health insurance system. However, significant disparities still exist between urban and rural areas. One way in which this disparity manifests itself is through staffing. Facilities and hospitals in urban areas are staffed with well-qualified professionals whereas many of those in rural areas still suffer staffing shortages. The government has attempted to deal with this disparity by funding the training of rural physicians.

China uses “medical alliances” to enhance the integration and coordination of care. Different models of medical alliances exist depending on the geographical setting of care. Urban medical alliances rely on the leadership of a tertiary medical center and integrate care with public hospitals as well as clinics. Alliances at the county level are led by a county-level hospital that integrates care with rural health centers. There are also alliances that rely on connecting patients in remote areas to health centers through web-based technology. These alliances are comparable to the United States concept of “medical homes,” which are meant to provide patients with access to high-quality primary and preventive care as well as enhance continuity of care for those with chronic illnesses.

Separate providers have their own EHR systems, but there remains little integration between the various systems of providers. However, facilities within the same medical alliance (as described above) do share EHRs. Therefore there is potential for the adaptation of a wider EHR system if the medical alliance model of care is successful.

In order to control costs and encourage cost-effectiveness of care, local health authorities have experimented with alternatives to fee-for-service physician reimbursement including inpatient care DRGs, global budgets, and capitation.

United Kingdom

The country’s health care system operates under a banner of universal access for all citizens that is administered by the National Health Service (NHS).

The health system uses the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to adjudicate which treatments and drugs patients have a right of access to. Similar to the Australian case with prescription drugs, these judgements are based on both clinical and cost effectiveness. For those treatments that have not undergone approval by NICE, the health system relies on local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to make evidence-based decisions.

There is generally minimal or no cost sharing required of the patient for many services provided under the NHS. Furthermore, in order to provide a financial safety net for vulnerable groups, the NHS system does not require prescription drug copayments for children under age 18, the elderly aged 60 and above, low-income residents, pregnant women and people with certain illnesses or disabilities.

The U.K.’s health care system uses a variety of alternative fee-for-service provider reimbursement schemes to incentivize value. Capitation represents about 60% of physician income and is risk adjusted for parameters such as age, gender and morbidity. Performance-based bonuses account for approximately 10% of physician income. Finally, DRGs are the predominant form of reimbursement for hospital services.

The key institution that is responsible for quality management is the Care Quality Commission (CQC). It sets benchmarks and standards for quality and safety. All private providers are required to register with the CQC. Patient experience and complaints are overseen by Healthwatch England while information on the quality of providers is published on the NHS’ website. Physicians are incentivized to improve quality of care through the Quality and Outcomes Framework. Under this framework payments are made for meeting evidence-based benchmarks. They are also responsible for care coordination and there are further financial incentives available to manage the care of the chronically ill.

Beginning in 2015, the NHS introduced a set of innovative models of care known as “vanguard sites”.[6] The aim of these models is to reduce costs of care while enhancing its integration and coordination. The NHS describes five types of models:

- Integrated primary and acute care systems—They are meant to integrate care between general practitioners, mental health providers and hospitals.

- Multispecialty community providers—These aim to move specialty care away from hospitals into the community.

- Enhanced health in care homes—This provides better integration of health care and rehabilitation services for the elderly.

- Urgent and emergency care—Provides new ways to integrate care in order to reduce the stress on emergency departments.

- Acute care collaborations—Links hospitals in order to improve their viability and reduce variability in costs and outcomes.

France

Based on the notion of solidarity that underlies the French social protection system adopted after World War II, the country’s health care system provides universal access to health care for its citizens and permanent residents. Access to specific services is dictated by the national government, which stipulates which treatments and drugs are covered by the country’s universal health system.

Average patient cost sharing levels are comparable to those found in other nation’s programs (for example, the United States’ Medicare program for the elderly and disabled), with the coinsurance level for inpatient services at 20% and physician services at 30%. There are some elements of “value-based insurance design” in the cost sharing structure of prescription drugs where the copayments vary according to the therapeutic effectiveness of the drug. For example, insulin medications have no coinsurance.

It is interesting to note that balance billing by providers (i.e. billing patients above levels covered under the universal system) is permitted. In order to provide financial protection to patients, this practice is discouraged or forbidden in some health care systems, notably in England’s NHS (discussed above) as well as the Medicare program in the United States. In France, individuals can purchase supplemental voluntary health insurance that covers the costs of such balance billing. Furthermore, low-income citizens are entitled to free voluntary supplemental insurance. There are also cost sharing exemptions for patients that have certain chronic illnesses.

Among physicians, FFS remains the predominant form of reimbursement. However, physicians are offered an annual capitation to coordinate care for patients as well as annual bonuses related to the use of EHR, preventive services (e.g. immunizations), compliance with care guidelines as well as generic prescribing.

The French health system makes use of the following institutions to regulate quality in the health care system:

- The French Health Products Safety Agency—The agency is responsible for assessing and approving the safety of all health products and devices.

- The National Agency for the Quality Assessment of Health and Social Care Organization—It evaluates safety and patient experience, particularly for vulnerable groups such as children and the elderly.

- The National Health Authority—It is responsible for assessing the effectiveness of health technology, drugs and medical devices as well as accrediting providers. The agency also publishes evidence-based care guidelines for a specific set of chronic illnesses.

- CompaqH—Together with the Ministry of Health, it publishes the performance of providers based on select indicators. Critically, financial incentives and penalties are not tied to public reporting of these indicators.

The country’s health care system continues to grapple with the challenges of coordination of care as well as the comprehensive use of EHRs. EHRs are used by some providers but a fully integrated nationwide system does not exist. An agency known as ASIP Santé has been created by the government to encourage the construction of a national EHR system.

Conclusion:

Patient access (both clinical and financial), quality of care, and innovation are key factors in evaluating the ability of a country’s health system to meet the health needs of its citizens. These factors also indicate the extent to which “value-based” care is being provided.

While all the countries that we have discussed offer their citizens and residents universal access to health care, they approach the issues of patient access, quality, and innovation in differing ways that reflect their unique institutions and values. Some countries’ health systems are tightly controlled at the national level, while for others the national government sets general guidelines and leaves it to localities to ensure that access and quality are adequate.

All the health systems that we have discussed also have challenges that they are still dealing with. Most of these revolve around the coordination of care, adoption of comprehensive nationwide EHR systems, and addressing health disparities among marginalized populations.

MITCHELL MOMANYI, MAAA, FSA, is a consulting actuary with Milliman.

References

[1] Conversions are current as of June 10, 2019, from Morningstar. [2] This is the medical ethics principle of “non-maleficence” applied to patient out-of-pocket costs [3] International Hospital Pricing Authority (IHPA). National Efficient Price Determination 2020-21. https://www.ihpa.gov.au/publications/national-efficient-price-determination-2020-21. [4] Commonwealth Fund. International Profiles of Health care Systems. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/_media_files_publications_fund_report_2017_may_mossialos_intl_profiles_v5.pdf [5] Meng Qingyue, Mills Anne, Wang Longde, Han Qide. What can we learn from China’s health system reform? BMJ 2019; 365 :l2349 [6] National Health Service. Models of Care. https://www.england.nhs.uk/new-care-models/about/