By Srivathsan Karanai Margan

Opportunities abound in this burgeoning space—but so do pitfalls

A metaverse is an interlinked network of physical, augmented, and 3D virtual worlds that is still in its formative years. Several companies are currently working to create their own versions of a metaverse platform. Many companies from different industries have started investing in the metaverse to establish their virtual presence.

This article discusses the metaverse, use cases that are being explored, legal issues that should be sorted before it goes mainstream, and how the insurance industry is impacted.

Much ado about metaverse

Metaverse is a hotly discussed topic, but we still don’t have a commonly accepted definition for it. It is said to be a shared 3D virtual space that people can access using virtual reality (VR) headsets, augmented reality (AR) applications, and other devices such as computers and mobile phones. The metaverse will resemble our physical world with digital representations of people, places, and objects. A user entering the metaverse will take an animated digital avatar to interact, socialize, play, work, and transact there.

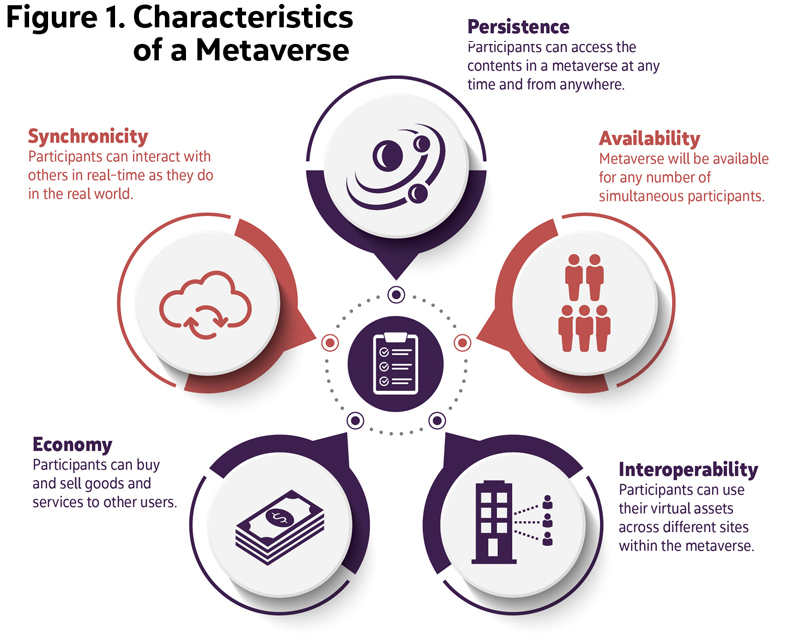

A metaverse is classified as closed or open depending on its ownership and technological aspects. A closed metaverse is owned by big tech companies, built on web 2.0, and hosted on a centralized server. On the other hand, an open metaverse is democratically owned and controlled by global users, built on web 3.0, and hosted on a decentralized network. They are further classified as a customer or industrial metaverse based on the segments they cater to or activities they perform. While the focus of the former is to enrich the experience, the latter aims at improving industrial efficiency. Companies such as Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Roblox, and Fortnite are working on closed metaverses, whereas Decentraland and The Sandbox are building open metaverses. A metaverse has five important characteristics: persistence, synchronicity, availability, economy, and interoperability (see Figure 1).

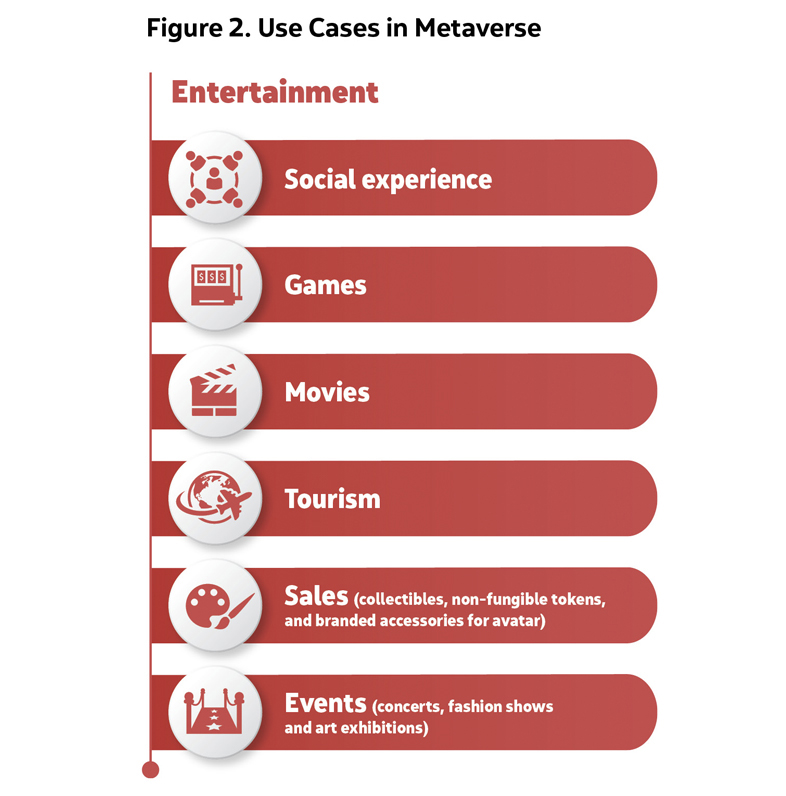

Currently, companies from several industries—gaming, retail, music, fashion and cosmetics, sports, education and training, art, automotive, tourism, and manufacturing, among others—are testing the metaverse space. The business use cases span a spectrum of activities from entertainment to business interaction (see Figure 2). However, the primary area of interest across companies is to establish a virtual presence to provide an immersive user experience, work collaboratively, or promote their goods and services. The companies are investing in virtual assets that include real estate and property to create their virtual offices and shops.

Several technologies from the fourth industrial revolution (4IR), such as AR, VR, artificial intelligence, 5G, the internet of things, and decentralized ledger technology, have come together to create the metaverse. These technologies are still evolving and are at various stages of the maturity curve. Regulatory bodies across the world are assessing the risks and legal issues arising from them individually to enact laws andgoverning principles. The metaverse, being a confluence of these technologies, makes it difficult to predict combinatorial risks—any attempt to do so is mere guesswork.

Legal clouds around metaverse

Anyone conversant with the world of video games will be aware of virtual realms where people use an avatar to play with others. No legal consequences arise when one player intentionally attacks someone—that adventure is the crux of the game. In comparison, the metaverse unfolds a virtual world that allows several activities, of which gaming is just one. So, it seems reasonable to expect many niche and complex legal issues to arise because of the interactions happening 1) among avatars, 2) between companies and individuals, and 3) between metaverse providers and the participants.

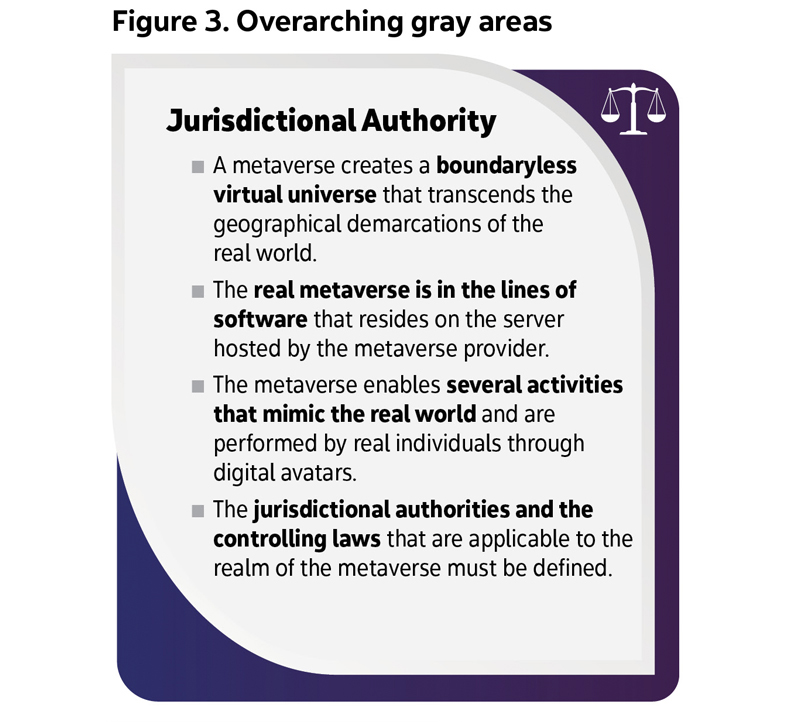

Before delving into these transactional issues, two overarching gray areas regarding the jurisdictional authority and the legal status of the avatar must be addressed (see Figure 3).

Other legal issues could arise in areas such as data privacy, data localization, intellectual property, assault and battery, real estate, and financial compliance. These conflicts can be grouped under two broader categories: those we are already familiar with and those that are potentially new. For the known issues, can existing laws in the physical world be grandfathered in the virtual world or repurposed? Regarding new issues, everything that could potentially go wrong should be considered to frame the governing principles and laws to prevent them.

- Data privacy: Data privacy issues relating to the metaverse could be an extension of those already being faced in a digitally connected world. For regulating them, existing privacy regulations could suffice. However, owing to its objective of providing an immersive experience, the data collected for the metaverse could be more invasive than what is sourced today. Real-time tracking of biometric data such as facial expressions, eye movements, vocal inflections, breathing rate, and body temperature obtained from the VR/AR devices and sensors could be misused to exploit the user or for commercial gain. Considering the sensitivity of data, privacy regulations will have to be suitably amended for the new data exchanged.

- Data localization: Several countries are enacting laws for data localization that impose restrictions on the data leaving the country in which it is sourced. Clarification must be provided regarding applying this restriction in the metaverse, which is a boundaryless parallel world, albeit a digital one.

- Intellectual property: Given that the metaverse allows avatars to work together, clarification is required on protecting intellectual property when some anonymized users collaborate to create something new. The inventions in the metaverse will be mostly software-based, and hence could be termed as “abstract ideas.” The challenges in the existing processes for patenting abstract ideas must be revisited. Companies setting up their metaverse sites may want to preserve their real-world patents on the metaverse. In such cases, the questions would be whether their existing patents will be extended to the metaverse, or whether a fresh filing must be done. If a fresh filing is needed, will the existing patent be pardoned during the prior art search?

- Assault, battery, and harassment: The course of legal action when one avatar assaults or harasses another avatar in the metaverse will have to be defined. Though a user could feel the sensations by wearing haptic vests and gloves, an assault in the metaverse is difficult to prove as it does not leave behind any actual bodily injury. In the case of sexual harassment, existing laws do not require any physical contact to consider it as such. However, it must be clarified if the harassment of a virtual avatar could be legally deemed as that of the actual user and hence a punishable act.

- Regulating virtual assets: With virtual assets such as cryptocurrencies, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and virtual real estate driving the economy in the metaverse, the definition of what “owning” anything in the virtual world means must be considered. Besides, there is no uniformity in how these assets are classified for regulation and taxation. While some countries treat them as digital assets, others consider them as property, art, commodities, or securities.

These issues must be resolved for the much-regulated insurance industry to take a serious plunge into the metaverse space to conduct business in it and provide cover for its risks.

Insurers picking their avatars

The concept of the metaverse is in the early stages of shaping up. Metaverse-specific risks can be clearly understood only after the metaverses are made available to all companies and individuals. Until then, all discussions on insuring the metaverse are hypothetical and speculatory. As it matures, several new companies performing new activities could emerge in the metaverse. All the stakeholders—metaverse providers, companies that own a site, third-party service providers, and individual users—will require first-party and third-party insurance cover for the risks they face. For insurers, the metaverse will be another addition to the growing list of intangible risks that they reckon with.

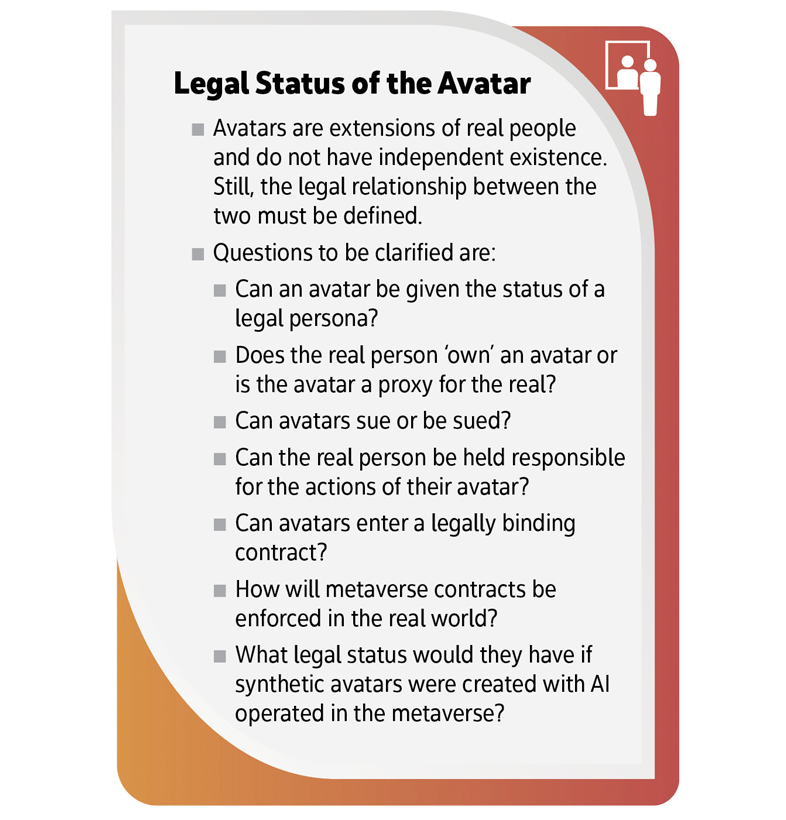

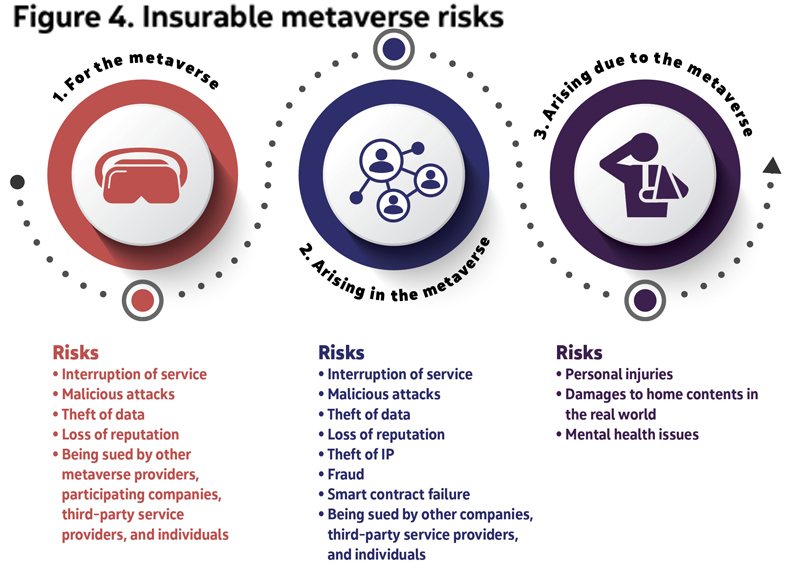

The approach insurers take toward the metaverse will vary based on whether they want to be participants or providers of risk cover. Current interest is skewed more toward the former, where they explore options to establish their presence for creating immersive and engaging virtual business interactions. As the virtual world takes proper shape, insurers will step into designing products for metaverse risks. I believe the risk cover will fall under three categories: for the metaverse, arising in the metaverse, and arising due to the metaverse (see Figure 4). The risks in the first and third categories will be predominately extensions of those that are already being covered, and hence existing covers can be extended for their metaverse namesakes. The second category will have both known risks (for which the existing covers must be remodeled to include the metaverse dimension) and several new risks.

When contemplating risks, cyber and liability risks qualify for further elaboration and emphasis—cyber for its complexity, and liability for the enormity and grayness surrounding it.

Cyber insurance

The metaverse is seen as a culmination of digital and 4IR technologies, and hence it will increase the risk surface for a cyberattack. Cyber risks related to metaverse can fall into five types:

- Another source for the known risks that insurers already cover—for example, there are risks related to metaverse as a platform.

- Extension of the existing risks, but the metaverse dimension is new—for example, disclosure of private information, government investigations and regulatory proceedings, data restoration, and ransomware payments.

- A known real-world non-cyber risk transforms into a digital risk—for example, virtual events that are scheduled in metaverse could face cancelation because of a cyberattack or a server outage.

- New and unknown risks. For example, a cyber-attack could shut down a company’s site in the metaverse. However, unlike in the real world, this could result in a loss of attraction or a loss in the market value of the digital assets in the metaverse. Conventional policies compensate for the cost of restoring data to its original state, but they do not cover the reduction in value. Insurers must address this gap by either designing a new cover or excluding this risk explicitly. Another example is regarding the business interruption losses that a company suffers after a cyber-attack. In the future, several pure metaverse companies could emerge that have their presence only in the virtual world. A cyberattack or server outage will cause business losses for which a new non-damage business interruption cover will have to be designed.

- Hybrid risks emerge as the boundary between the real and virtual realms disappears—for example, a targeted attack on data from connected devices that are fed to the metaverse, resulting in a real-world disaster.

Liability insurance

A metaverse allows several real-world functions, which makes it essential to scrutinize the corresponding liability-related risks. A few examples are given below:

- The metaverse provider is the one that designs the hardware and software that runs it. Hence, it is reasonable to expect more accountability and responsibility from it. The demarcation of the liabilities of the provider and the participating companies will have to be specified.

- Long-term use of AR/VR headsets could cause physical and mental harm to users. While individual users could sue metaverse providers or AR/VR device manufacturers, employees in the metaverse will sue their employers. The pricing of the traditional commercial general liability (CGL) and employers’ liability policies and the wordings in the contracts must be revisited.

- A similar assessment must be done for liability cover for offences such as defamation, and invasion of privacy that may occur in the metaverse.

- For Errors and Omissions (E&O), and Directors’ and Officers’ (D&O) liabilities, risks arising due to the approach to metaverse in the real world as well as the actions in metaverse will have to be factored in.

- In the future, several new metaverse-related

liability risks could arise. This will require finding answers to many

questions related to the responsibilities and accountability of companies. For

example,

- If policing algorithm avatars were introduced in the metaverse, what would be the legality of such avatars? Will these algorithmic avatars—and in turn the company or metaverse provider—be held responsible for an unfair and discriminating algorithm?

- Concerning harassment of avatars in the metaverse, it is possible that by the time metaverses mature, they will include an option for users to activate a safety bubble that would prevent other avatars from getting closer. While this could be an opt-in provision for individuals, the responsibility of companies in their virtual offices is to be specified. Should a company activate the safety bubble as a default feature with an opt-out provision? Will imposing a default safety bubble be considered an invasion of rights, resulting in a lawsuit? What will be the liabilities of metaverse employees if they see such harassment happening in their office?

- Reputation risk due to cyberattack could create a hybrid liability risk that permeates real and virtual realms. For example, if a virtual office of a company gets bad publicity for a harassment issue, it could result in a loss of attraction and business in the metaverse. Such an event could spill over to the real world as well, thus creating a bad reputation for the company involved. The reputation risk cover in the liability cover must factor in this eventuality.

In due course, insurance companies will sell virtual policies for metaverse risks from their virtual offices in the metaverse. These policies would be parametric smart contracts that are digitally signed and transacted in cryptocurrencies. As the boundary differentiating the real and virtual realms disappears, connected insurance data from IoT devices and sensors will be fed to the metaverse to create an interactive digital twin. Insurers could engage with this digital twin to assess risk, pricing, continuous monitoring, and claim adjustment. Insurers could offer metaverse cover as an extension or add-on to traditional contracts or as a separate policy. In both cases, they should examine policy wordings to ensure that real and virtual world risks are distinctively specified.

Where it leads to

The concept of the metaverse could take more than a decade to mature. While gazing into a crystal ball for the future of the metaverse, two contrasting visions emerge.

- First, the metaverse turns out to be a blockbuster hit and changes the way we live. Common standards are created for seamless collaboration and interoperability among different metaverses. The avatar effortlessly travels from one metaverse to another without the user changing the device.

- Second, the metaverse hype fizzles out and a long technological winter ensues.

Irrespective of the scenario that unfolds in the future, insurers must respond and participate in the metaverse story. They must at least start working on their existing contracts to either explicitly exclude metaverse risks or include and appropriately price them. If insurers abstain or follow a go-slow approach, on a normal front, they will face silent metaverse claims and on an elevated front, they will miss opportunities to engage with Gen Y & Z customers, manage connected insurance risks effectively, and create products for the metaverse risks.

SRIVATHSAN KARANAI MARGAN works as an insurance domain consultant at Tata Consultancy Services Limited.

References

Kazakis G., Irvin S., Levitt S., Buchanan J.; “Insuring the Metaverse: New Worlds Meet Old Policies”; Bloomberg Law; April 8, 2022.