Applying Precept 13

Concerning Apparent, Unresolved, Material Violations of the Code of Professional Conduct

Preface

The Committee on Professional Responsibility of the American Academy of Actuaries has developed this discussion paper for use by Actuaries[1] at their discretion.

This discussion paper was not promulgated by the Actuarial Standards Board nor is it a product of the Actuarial Board for Counseling and Discipline. It is not a binding authority upon any Actuary. No affirmative obligation is intended to be imposed on any Actuary by this paper, nor should such an obligation be inferred from any of the statements expressed or suggestions made in this paper.

To the extent any conflict between this discussion paper and the principles set forth in the Code of Professional Conduct (Code) adopted by the five U.S.-based actuarial organizations[2] exists or could be inferred, the Code prevails as this discussion paper is not a rule or guidance similar to the Code or Actuarial Standards of Practice (ASOPs) and other applicable standards.

Actuaries are encouraged to share their comments on this paper with the Committee on Professional Responsibility to facilitate improvement in any future releases on this topic. Comments may be submitted to Precept13@actuary.org.

Introduction

It is arguable that a profession is only as good as its reputation. The credentialed members of the U.S. actuarial profession follow a code of conduct, as well as standards of qualifications and practice, to encourage credentialed actuaries to maintain high standards in their work and therefore inspire public confidence. Precept 13 of the Code of Professional Conduct requires actuaries to take action if they come across actuarial work that appears to violate the Code. Under Precept 13, they may (but are not required to) discuss the problem with the actuary whose work is in question. If that discussion fails to resolve the apparent violation, or if they choose not to have that discussion, they must report it to the Actuarial Board for Counseling and Discipline (ABCD).

In recent years, anecdotal statements from members of the profession indicate a disconnect associated with actuarial work product and Precept 13 of the Code: regulatory and other credentialed actuaries say they “frequently” see work that appears to violate the Code, yet the average number of cases reported to the ABCD each year has generally not risen. This suggests that some actuaries who have come across actuarial work that potentially violates the Code are not reporting it—and thus likely violating Precept 13 of the Code.

Some Actuaries have expressed concern that compliance with Precept 13 in reporting an actuary to the ABCD could open them to legal liability. In looking further into such liability concerns, the Academy’s Council on Professionalism found only one lawsuit against an actuary who reported an actuary to the ABCD. In that case, the court eventually threw out the matter altogether. The ABCD has an obligation to keep all cases reported to it confidential under the Academy bylaws. The ABCD is only permitted to report the results of its investigation to the member organization(s) of the actuary reported to the ABCD (known as the “subject actuary”) if the conclusion is that a material violation of the Code has occurred and the ABCD recommends discipline.

Of course, in the United States, any party may commence a lawsuit against any other party for any reason, and there is no guarantee that some subject actuary will not attempt such an action against the party referring a subject actuary (such reporting party known as the complainant). However, after analyzing known historical facts and circumstances, the risk of legal liability for reporting work that may violate the Code to the ABCD is extremely low.

To be clear, the overwhelming majority of actuaries perform their work in accordance with the Code. But it takes only a few publicized cases of bad work to ruin the reputation of the profession as a whole and undermine public trust in the profession. This may be especially true if the case was not reported by someone within the profession but was uncovered by someone outside the profession, a legal investigation, or the media.

Currently, the U.S. actuarial profession generally regulates itself with the help of the Code, Actuarial Standards of Practice, and Qualification Standards for Actuaries Issuing Statements of Actuarial Opinion in the United States supported by the American Academy of Actuaries. If, however, actuaries fail to report actuarial work violative of the Code—and companies, governments, employees, customers, and citizens end up bearing the eventual costs—the public and its representatives may lose faith in the profession’s ability to self-regulate with integrity and effectiveness.

Ultimately, preserving the right of actuaries to self-regulate lies with you, the practicing actuary.

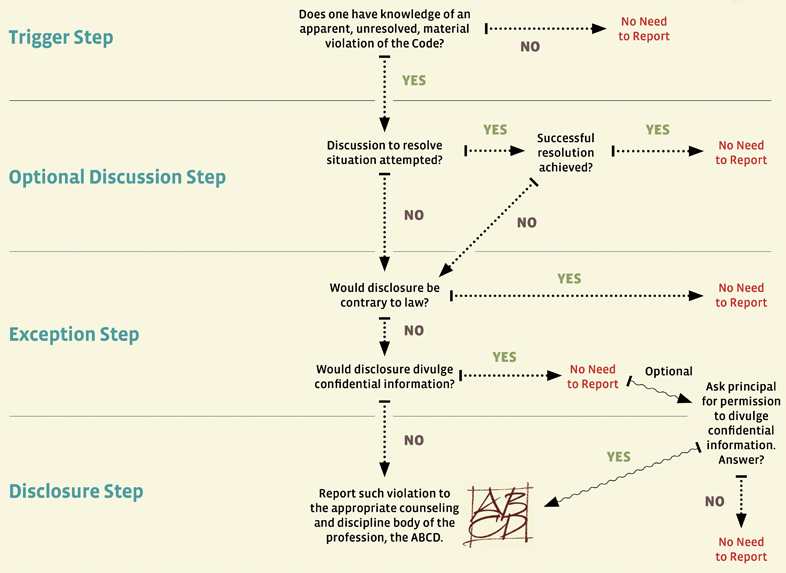

| Overview of Precept 13 For convenient reference, Precept 13 is restated here in its entirety. Please refer to Appendix A (page 39) for a basic Precept 13 process flowchart. Precept 13 and its Annotations Violations of the Code of Professional Conduct PRECEPT 13. An Actuary with knowledge of an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code by another Actuary should consider discussing the situation with the other Actuary and attempt to resolve the apparent violation. If such discussion is not attempted or is not successful, the Actuary shall disclose such violation to the appropriate counseling and discipline body of the profession, except where the disclosure would be contrary to Law or would divulge Confidential Information. ANNOTATION 13-1. A violation of the Code is deemed to be material if it is important or affects the outcome of a situation, as opposed to a violation that is trivial, does not affect an outcome, or is one merely of form. ANNOTATION 13-2. An Actuary is not expected to discuss an apparent, unresolved material violation of the Code with the other Actuary if either Actuary is prohibited by Law from doing so or is acting in an adversarial environment involving the other Actuary. It is important to acknowledge that Precept 13, as an integral part of the Code, establishes principles with which Actuaries are required to comply. Unlike ASOPs, the Code contains no provision for deviation. Unlike other principles established by the Code that apply to the Actuary’s self-regulation of his/her own conduct, Precept 13 requires an Actuary to disclose apparent violations of the Code by another Actuary, barring resolution of the situation through discussion between the Actuaries, except where such disclosure would be contrary to Law or reveal Confidential Information. This can, at the very least, be uncomfortable for all parties involved. |

The Importance of Self-Regulation

A profession is generally defined as an occupation that requires substantial training and the study and mastery of specialized knowledge in a defined subject matter area.

Professions are often important to the well-being of the general public and smooth functioning of society. Therefore, the public expects individual members of a profession to meet higher standards than those who work in non-professional fields. Typically, an individual’s profession is signified by membership in a professional association or organization, for example, the American Academy of Actuaries and the other U.S.-based actuarial organizations.

Some professionals may be subject to licensing by government entities to practice their profession (for example, Enrolled Actuaries[3]). In some cases, governments may rely on a profession to regulate itself if such self-regulation assures competent and ethical services.

In the actuarial profession, self-regulation takes the form of establishing and maintaining

- Rules for admission to the professional organizations, including basic education and/or experience, as well as continuing education requirements for maintaining professional membership;

- A code of professional conduct requiring adherence to ethical principles;

- Qualification standards and standards of practice that provide the framework for the Actuary to provide consistency in the delivery of professional services and work products; and

- Rules addressing how and when members may be counseled, disciplined, or removed from professional membership through a disciplinary process that includes due process.

Professions typically provide opportunities for continuing education so that members remain up-to-date with developing knowledge in the profession. Professions also typically engage in research to develop new knowledge and publish findings and other information relevant to their members’ areas of practice.

Advantages of Self-Regulation

The principal advantage to a profession of self-regulation is the autonomy it provides. That is, a self-regulating profession and its members remain independent of undue external influence and exercise self-determination. Thus, the members remain free to set the direction the profession will take within the constraints imposed by applicable law and the practical and ethical responsibilities that come with self-regulation. Also, members of a profession will generally be the most knowledgeable and best trained to determine whether professional standards have been properly applied and adhered to.

When a profession, with the enlightenment that comes from expertise in its subject matter, undertakes to regulate itself, it can be more confident that requirements, restrictions, or expectations imposed on its membership will be rational and effective.

Potential Pitfalls of Self-Regulation

Another principal component of self-regulation is control of the profession’s membership. Two aspects of this control are the establishment of membership criteria or requirements for entry to the profession through professional organizations, and the exercise of disciplinary procedures that may remove members from professional organizations. If not done properly, these activities might be viewed as limiting competition or as establishing conformity of views, opinions and actions of greater benefit to the profession and its membership than to the general public.

Failure to adequately meet the requirements of a well-defined self-regulation process and apply them consistently can result in the loss of public trust, affecting all members of the profession.

Regardless of one’s views on self-regulation, the fact that the actuarial profession has remained self-governed for decades supports the notion that the existing actuarial organizations have served the public interest in the delivery of professional actuarial services.

Background

Identifying and reporting violations of a professional body’s code of conduct—whether the violation is committed by a colleague, a peer, an employee, or one’s own supervisor—may prove to be one of the most challenging and stressful requirements placed on those practicing in a self-regulated profession. What benefit could a profession derive from requiring its membership to approach or even “call out” one member whose work or behavior fails to conform to another member’s understanding of the established norms and expectations of the profession? Professional organizations establish codes of conduct that apply to their members to explicitly identify the professional and ethical principles that form the basis for a profession’s service and responsibility to the public. This enables the public to have faith that someone with the professional organization’s credentials may be trusted to put core principles over any conflicting personal or monetary interests. The typical objective of a code is to require all members of the professional organization to adhere to high levels of well-defined professional conduct, qualifications, and practice. A member who violates any of the principles stated in the professional organization’s code or rules may be subject to counseling or discipline. Discipline may range from a private or public reprimand to suspension or even expulsion from the organization.

Codes of professional conduct, standards of practice, and disciplinary procedures are essential to support and protect the integrity of a self-regulating profession. In some professions, codes of conduct require their members to report any other member’s apparent violation of the professional organization’s code of which they become aware to the appropriate counseling and disciplinary body of the profession.

There is usually little objection by a professional organization’s membership to the codes or rules of conduct established by the profession. For obvious reasons, most rules of conduct such as professional integrity or adherence to professional standards are unobjectionable. But adherence to a code provision like Precept 13 of the Code, which requires members to report the apparent violations of the Code by other members, may inherently create some difficulties for all parties involved. Nevertheless, members of a self-regulated profession are usually the best equipped to identify those who breach its code, especially in highly technical and/or esoteric areas of practice.

The approach taken by the five U.S.-based actuarial organizations with respect to self-regulation has been recognized as a potential model for other professions to follow.

“The banking industry can learn from other professions. The American Academy of Actuaries may be the best model for the banking community to study. Independent of the

U.S. government, but cooperative, the Academy sets and controls the standards for the actuarial profession. Importantly, the Academy has the power to expel, suspend and publicly reprimand members. Banking needs self-policing powers.”[4]

The Importance of Knowing the Code

To report another Actuary’s apparent violation of the Code, it is helpful to have a good working knowledge of the Code, as well as the ASOPs developed by the Actuarial Standards Board and the qualification standards promulgated by the Academy’s Committee on Qualifications. A residual benefit of being prepared to exercise the judgment necessary to apply Precept 13 is that it strengthens the Actuary’s awareness and understanding of the Code and applicable standards.

Common sense and reasonableness remain relevant and applicable in all situations. If an observed activity by another Actuary doesn’t look, feel, or sound right, there may very well be a possible violation of the Code.

It is also important to recognize that an Actuary has no obligation to build an investigative, legal-style case file regarding the observed activity. If investigation is required, it will be performed under the direction of the body that investigates such matters (in the United States, the ABCD).

In applying Precept 13 an Actuary is expected to exercise professional judgment in determining whether an apparent material violation of the Code has occurred. One overriding suggestion in interpreting the meaning of language used in the Code or ASOPs is to apply common sense and reflect on the purpose of the Code (as stated in its preamble):

“The purpose of this Code of Professional Conduct (“Code”) is to require Actuaries to adhere to the high standards of conduct, practice, and qualifications of the actuarial profession, thereby supporting the actuarial profession in fulfilling its responsibility to the public.”

When interpreting the meaning of words and language in the Code or in ASOPs for the purpose of considering whether a violation appears to have occurred, reasonable differences in the meaning of the words or language in a specific Code Precept or ASOP may be expected. Often, such differences in interpretation may be cleared up through a discussion between two Actuaries with differing views. It is not necessary to form an opinion that there has been an apparent, material violation of the Code to initiate such a conversation.

Interpreting the language of the Precept to determine the circumstances under which the reporting of an apparent violation is necessary has raised questions, many of which are discussed in this paper. It is important to keep in mind that members who belong to a profession are expected to use professional judgment and follow the rules of that profession.

| Hypothetical Example Example 1: Concerns With Procedure Situation You (the Actuary) have taken over a defined benefit pension plan from another Actuary. On reviewing the plan you develop some concerns about the way the previous Actuary has administered or valued the plan. Your concerns persist even though you recognize that Actuaries may have different approaches to the same problem. Discussion You should first decide whether the previous work results in a material violation of the Code. Your concern might be based on evidence that guidance provided by an ASOP was not followed without explanation or justification for the deviation in the work product you reviewed. In this case, an appropriate initial step may be to discuss the situation with the previous Actuary. The circumstances under which you replaced the previous Actuary may add complexities. The previous Actuary has an obligation under Precept 10 (Courtesy and Cooperation), Annotation 10-5, to cooperate and provide relevant information. Such a conversation may reveal information not available to you from your review of the earlier written work product and may eliminate your concerns. Alternatively, your discussion may alert the previous Actuary that he or she omitted necessary documentation or failed to apply an ASOP properly. In such a case, the matter may be resolved by the previous Actuary recognizing the error and cooperating with you in making the necessary corrections and explanations. In this case, you might consider the matter resolved and feel that you have complied with Precept 13. Of course, the previous Actuary may refuse to discuss the matter with you. Such a lack of cooperation may be indicative of an apparent violation of Precept 10 in addition to the apparent violation that caused you to seek cooperation in the first place. Or, the previous Actuary may not admit or agree an error was made that resulted in a material violation of the Code, even though you remain convinced an error was made. The information that you become aware of as a result of your work for a pension plan is confidential. In addition to Precept 13, Precept 9 (Confidentiality) requires such Confidential Information to be kept confidential unless the Principal to whom you owe this responsibility authorizes you to release the information. If the violation is significant, you might feel compelled to seek such authorization to make a report to the ABCD. Alternatively, you might consider whether a report could be made without disclosing any Confidential Information. For example, an inappropriate method or process leading to an apparent, material violation of the Code might be described without the need to reveal Confidential Information. If a concern regarding confidentiality persists and the Confidential Information would need to be an essential part of any report, you might consider seeking guidance from the ABCD in the matter, as long as seeking such guidance would not violate the terms of confidentiality. As the current Actuary for the plan, you have a clear obligation to your Principal. Any changes you are considering or planning to make ought to be discussed with your Principal, including reasons for the changes. |

Issues Considered in This Discussion Paper

- Why do we need a Precept 13-type requirement at all?

- Precept 13 states that an Actuary with knowledge of an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code by another Actuary “should consider” discussing it with that Actuary (subject to the exception noted in Annotation 13-2) in an attempt to resolve the apparent violation. How does an Actuary approach such a discussion?

- Actuaries are required to disclose “apparent, unresolved, material” violations of the Code. What does “apparent” mean? How is an Actuary to interpret “apparent” in situations where he or she has only partial information or documentation? When does the Actuary determine that an apparent violation has reached the point that it cannot be resolved? What standard does the Actuary apply to determine whether something is material?

- Precept 9 (Confidentiality) may also influence an Actuary’s decisions regarding disclosures to be made while adhering to Precept 13. To what extent is maintaining confidentiality a reason, rather than an excuse, not to disclose?

- Issues of a legal nature may cloud an Actuary’s decision to report apparent, unresolved, material violations of the Code. How does or should Law,[5] as defined in the Code, be allowed to affect disclosure under Precept 13?

- Actuaries may deviate from the specific guidance provided in ASOPs with proper disclosure and justification for such deviation. How is an Actuary to interpret compliance with the Code when deviations from an ASOP, properly disclosed, have been made?

- Actuaries are expected to exercise professional judgment[6] with respect to the applicability of a Standard or where no Standard exists. Does Precept 13 affect the use of professional judgment?

- Under what circumstances would a failure to report an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code become a violation of Precept 13 itself?

- Within what time frame should an Actuary disclose an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code?

Issue: Why the Need for Precept 13?

Regulatory activities of a profession are carried out for practical and ethical reasons and help promote the public interest and maintain the profession’s integrity and reputation. In addition, if a self-regulating profession does not prevent unethical behavior and practice, it is highly likely that some other regulator will emerge who can and will assure ethical behavior and practice. A well-defined process of self-discipline and counseling is a key element of a self-regulatory approach.

A profession may certainly react to complaints made by non-members (i.e., the general public) or to public incidents indicative of bad behavior on the part of one of its members. In fact, it should be expected to do so. However, incompetence or unethical behavior may not always be obvious to someone with little mastery of the profession’s specialized knowledge and practices. Therefore, just as a profession may establish investigative and disciplinary bodies to adjudicate a complaint made against a member, it must rely on and expect its members to identify and report any apparent violation of its code of conduct of which members become aware.

The U.S.-based actuarial organizations that have adopted the Code primarily rely on their members to monitor compliance. The Code requires members to report potential violations of the Code to the organization established to provide the profession with counseling and recommended discipline, which in the United States is the ABCD. Members should take on this responsibility to justify and encourage public confidence in the profession’s self-regulatory role. Members should do this in the public interest, the profession’s interest, and their own interest.

Issue: One-on-One Resolution

Precept 13 states that an Actuary “should consider” discussing an apparent violation with the Actuary believed to have committed such violation. A key to initiating such a discussion would be to recognize that the conversation is about an apparent violation of the Code. Therefore, it would be prudent for the Actuary to approach a situation like this in an inquisitive, rather than accusatory, style.

Consider that the purpose of such a discussion is to gain a better understanding of the situation, in order to eliminate or resolve any material violation that may have occurred. If a one-on-one discussion is initiated, it should be for the purpose of creating a better understanding of the relevant facts and circumstances, including how the Code and/or relevant ASOPs have been applied. A successful discussion should lead to a common understanding of the facts, circumstances, and application of the Code and ASOPs, resulting in a resolution of the apparent material violation. For example, this may result either in the questioning Actuary becoming aware of information that changes his or her opinion regarding the apparent material violation or in the questioned Actuary revising his or her approach in the future and taking appropriate action to correct past violations.

For example, an Actuary may believe that a violation of Precept 7 (Conflict of Interest) has occurred because another Actuary, whose work is in question, provides actuarial services to two clients who are believed to be competitors on the matter to which the services relate. A discussion may reveal that the questioned Actuary has, in fact, complied with Precept 7 by determining that he or she can perform actuarial services for both parties fairly, informing his clients and getting express written agreement from each regarding the work being done. The discussion may reveal, for example, that although the clients are normally competitors, they have a common interest and partnership in the project, of which the questioning Actuary had not been aware.

A discussion can, therefore, be a good learning opportunity for both Actuaries. The Actuary who is doing the questioning may learn something new or gain new insight. The Actuary being questioned may not have realized how his or her action was perceived or may be made aware of an issue that he or she had not previously considered.

The nature of the discussion will usually depend on the nature of the relationship that exists between the two Actuaries. Colleagues may handle a discussion more casually as a routine part of working together, for example. That is, such a discussion may be stimulated more by an existing working relationship or friendship and a common or supportive interest in producing a good work product than by any perceived material violation of the Code.

| Hypothetical Example Example 2: Cumulative Errors Situation Using the scenario described in Example 1, assume the error with respect to any one plan is small and not material for any given plan but that the same error was made consistently in a large number of plans taken over from the same previous Actuary. Discussion At the very least, you should discuss the situation with the previous Actuary. The previous Actuary may agree that what you observed was in fact an error that won’t be repeated in the future. If you observed the error in only one instance and it was immaterial, then judging it to be immaterial would be logical and the matter may be considered to be resolved. However, if the error is repeated consistently, indicating a lack of understanding of an actuarial process, it may lead you to question the qualification of the Actuary to perform the work (Precept 2, Qualification Standards), thereby triggering a Precept 13 need for disclosure to the ABCD. |

Likewise, a subordinate/manager or employee/employer discussion regarding potential material violations of the Code may result from a formal peer review process and be considered routine, non-confrontational, and educational in nature. On the other hand, a subordinate Actuary who believes his or her manager/employer, who is an Actuary, violated the Code might be concerned about keeping his or her job if he or she raises the violation.

Other relationships may exist between Actuaries who are involved in the same project. This common involvement implies that they can be knowledgeable enough about each other’s work product to form an opinion regarding a possible violation of the Code.

These situations may present difficulties with respect to initiating such a discussion. Although Precept 13 specifies a “discussion,” the awkwardness of initiating such a discussion in a situation like this might be addressed by a letter of inquiry pointing out any perceived problems and asking for clarification.

The Code does not require Actuaries to initiate a discussion with an Actuary believed to be violating the Code. An Actuary’s certainty regarding his or her knowledge of an apparent violation may be strong enough and the relationship between the two Actuaries may be of such a nature that it would be inappropriate or too confrontational to reasonably expect such a discussion to resolve the issue.

Clearly, if a discussion is not attempted or if, after a discussion, the questioning Actuary’s concern regarding an apparent material violation has not been alleviated, the apparent violation is unresolved. The Actuary, per the language in Precept 13 (“shall disclose”), has an obligation to report the apparent, material, unresolved violation to the ABCD, except where this would be contrary to Law or would divulge Confidential Information.

Issue: What Do the Words Mean?

The language of Precept 13 may be interpreted, subjectively, in different ways by different readers or in different ways depending on the situation. For example, the words “apparent,” “unresolved,” and “material” as used in Precept 13 may call for some interpretation.

“Apparent”

Underlying the common understanding of “apparent” is a recognition of the old adage that one cannot always judge a book by its cover. Generally, a material violation of the Code would have depth and would come as a result of some underlying activity or action on the part of the Actuary whose work is in question. Seeing only the surface appearance or result of some actuarial process with which one may disagree may give rise to suspicion but probably does not, by itself, rise to the level of creating “knowledge of an apparent violation of the Code.” Therefore, not every Actuary would be in a position to express an objective opinion on another Actuary’s compliance or non-compliance with the Code. Knowledge of another

Actuary’s apparent violation of the Code may require an Actuary to be privy in some way to the processes underlying the other Actuary’s work.

On the other hand, Actuaries should not use their incomplete access to relevant information or lack of experience in a practice area as an excuse not to comply with the requirements of Precept 13. To the extent that information routinely available to an Actuary regarding the conduct of another Actuary gives rise in his or her mind to concerns about professional behavior, he or she may have observed an apparent violation of the Code and ought to address it under Precept 13. This, of course, assumes that the “concern” was based on a reasonable interpretation of the information available to the questioning Actuary.

Judgment about what may or may not be apparent should be based prudently on a well-founded understanding of the circumstances giving rise to the question. A discussion with the Actuary being questioned may be necessary to better understand and interpret his or her actions. However, Precept 13 and the Code do not require Actuaries to undertake any investigative duties to resolve apparent material violations. That is a function of the ABCD. Nor does the fact that an apparent material violation has been reported definitively indicate that a violation has actually occurred. Again, that is for the ABCD to determine.

| Hypothetical Example Example 3: Product Development Projection Situation A product development Actuary with whom you work at an insurance company has developed projections for a proposed new product that show large losses for seven years before modest profits begin. Upon review, the CEO (not an Actuary) of your company does not believe the company’s board would approve a new product with such a projected earnings stream and directs the product development Actuary to revise the projection assumptions so that a more favorable earnings pattern can be presented to the board. The product development Actuary revises the projection per the CEO’s request. You discuss this matter with the product development Actuary, arguing that the revised projection does not comply with applicable ASOPs. The product development Actuary argues that, although the new projection deviates from the specific guidance provided in the applicable ASOP with respect to the assumptions used, the deviation has been disclosed and compliance with applicable ASOPs has been achieved. Discussion The actions of the product development Actuary in this example may stretch the guidance provided for deviation. The CEO did not provide a set of assumptions for the product development Actuary to use as an alternate to the assumptions originally used. Rather, the CEO directed the product development Actuary to find and use assumptions that would produce a better projection. It is possible that the Actuary disclosed this deviation from the ASOP in his work product, making users of the projection aware that the product development Actuary did not believe the assumptions used were reasonable. However, it seems unlikely that the product development Actuary would present a projection result based on his own assumptions and include an explanation of deviation from applicable ASOPs. In either case, in addition to an apparent violation of Precept 3 (Standards of Practice), there may be a violation of Precept 8 (Control of Work Product), which requires the Actuary to take reasonable steps to ensure that the work product is not used to mislead other parties. In this situation, the Actuary appears to be producing work at the direction of the CEO to do just that. If you cannot resolve the apparent violation of both Precepts, you must report a violation to the ABCD if you can do so without revealing Confidential Information or violating Law. |

“Unresolved”

“Unresolved,” as used in Precept 13, could be used to describe an apparent, material violation of the Code present or reflected in an actuarial process or draft work product, which is not modified or amended before the work product becomes final or has an opportunity to influence a user of the work product in a material way.

Resolution of such a violation of the Code as described in Precept 13 usually refers to one of two possible situations:

- An Actuary with initial knowledge of an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code by another Actuary may subsequently observe that the other Actuary, through self-directed changes in conduct or practice or through the acquisition and/or application of additional information, has effectively eliminated those initial concerns in the final process or work product. Therefore, the matter could be considered resolved without having a discussion with the Actuary in question.

- An Actuary who believes that Precept 13 may have been violated should consider a discussion with the other Actuary regarding the apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code in an attempt to resolve the issue. As a result of such a discussion, the Actuary may determine that his or her concern regarding an apparent material violation of the Code has been eliminated, either through the other Actuary’s provision of additional information or through the amendment or modification of the questioned process or work product. In these cases, the matter could be considered resolved.

“Material”

Annotation 13-1 provides a description of how “material” should be interpreted under Precept 13. Essentially, the annotation indicates that a violation is material “if it is important or affects the outcome of a situation.” It is immaterial or trivial if it does not. One could argue that Annotation 13-1 is not clear about when a violation of the Code becomes material because it indicates that materiality is determined by the effect a violation has on an outcome rather than the effect it might have (or is likely to have) on an outcome.

It may be helpful for the Actuary trying to understand the concept of materiality to review the definition of “materiality” in ASOP No. 1, Introductory Actuarial Standard of Practice,[7] and in the discussion paper “Materiality.”[8] While the overall concept of what is or is not material might be considered subjective, the general description of the concept of materiality provided in the Materiality discussion paper can be adapted to the circumstances of Precept 13.

Issue: Dealing With Confidentiality

Confidentiality would likely be an issue only for an Actuary who actually had access to or knowledge of the Confidential Information[9] related to the apparent violation.

Precept 13 is not intended to create a conflict with Precept 9 of the Code (Confidentiality). Therefore, Precept 13 does not require disclosure to the appropriate counseling and disciplinary body if such disclosure “would divulge Confidential Information.” This exception should be read in light of Precept 9, which allows disclosure of Confidential Information if authorized by a Principal or required by Law.

A decision that the only way an apparent violation of the Code could be reported would be to breach confidentiality may be a welcome but inappropriate excuse for an Actuary who is uncomfortable applying Precept 13. For this view to hold, the particulars of an apparent material violation may need to be so inexorably linked to Confidential Information that the disclosure of the apparent violation necessarily also would divulge the Confidential Information. Precept 9 and the exception in Precept 13 are clearly intended to prohibit inappropriate disclosure of Confidential Information.

The fact that Confidential Information is part of an activity or project that involves an apparent violation of the Code does not automatically mean that disclosing the apparent violation also involves disclosing the Confidential Information. An Actuary may want to consider whether it is necessary to divulge Confidential Information to disclose the apparent, material violation. For example, an Actuary may become aware that another Actuary involved in the same assignment has apparently violated Precept 11 (Advertising) by implying or claiming to have the expertise necessary to complete the assignment properly, which the Actuary apparently lacks. The first Actuary could disclose such an apparent violation of the Code without disclosing any Confidential Information related to the particulars of the assignment by disclosing information related only to the other Actuary’s lack of qualification.

A one-on-one discussion with the Actuary whose work is in question, as suggested in Precept 13, may also resolve the issue without disclosing any Confidential Information to anyone who does not already have authorized access to it.

While the Code does contain a definition of Confidential Information, it should be clear that information can be considered confidential on many different levels and for many different reasons. Confidentiality may be required by Law or a court. It may be imposed by contract or agreement (as in a nondisclosure agreement), or it may be a common course of business conduct in the industry.

Confidentiality may be requested or expected only in an attempt to limit the distribution of information on which no legal requirement for confidentiality can be or has been imposed. Generally, information is made or considered confidential for a reason. That reason usually involves a belief or probability that disclosure of the information outside of a circle of people authorized to receive it is likely to cause some harm to some lawful and legitimate interest—financial or otherwise.

An Actuary seeking options that would abide by the confidentiality requirements of Precepts 13 and 9 might consider requesting the entity imposing the confidentiality requirement to authorize a release from the requirement for the purpose of disclosing the apparent, material violation.

| Hypothetical Example Example 4: Strong Disagreement Situation The Code requires Actuaries to comply with Law and regulation but does not address the interpretation of Law and regulation. You have a strong disagreement with another Actuary regarding the application of a particular Law because you interpret it differently and you strongly believe that your interpretation is correct. There is no general consensus or common interpretation within the profession on the matter because the Law involved is relatively new and no regulatory experience yet exists. Discussion It is probably wrong to conclude that a Law has been broken and a material violation of the Code has occurred merely because of differing interpretations of how a Law or regulation should be applied. An appropriate approach in such a situation would be to discuss the matter with the Actuary with whom you have a disagreement. This discussion can be initiated in the context of Precept 10 (Courtesy and Cooperation)—in particular, Annotation 10-1—rather than Precept 13. That is, you would initiate a conversation to understand better the reasons for the other Actuary’s approach to compliance with the Law. Even though a discussion of the issue with the other Actuary may not result in a change of opinion, Actuaries should recognize that reasonable differences of opinion are to be expected. If the other Actuary has presented a reasonable argument for his or her interpretation of the Law, your disagreeing with it does not make it wrong. In this situation, it would be inappropriate for you to claim the other Actuary was violating the Code simply because your opinions are different. In many situations and under many circumstances, Actuaries must rely on the legal expertise and advice of those formally trained in that discipline. On the other hand, if you have a well-formed opinion that another Actuary has violated the Code, it would seem that you “have knowledge of an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code.” If you do not report that apparent, unresolved, material violation to the ABCD, you may have violated Precept 13. Rather than report an apparent Code violation, you could seek guidance from the ABCD and indicate precisely where you disagree with the work product of the other Actuary. The ABCD could assist in your evaluation of the specific circumstances and investigate. |

Issue: The Impact of Law and ASOPs

Precept 13 allows an exception to the reporting of an apparent violation if “…disclosure would be contrary to Law….” Per the Code, Law that imposes an obligation on an Actuary in conflict with the Code takes precedence. ASOPs permit deviation from the guidance ASOPs provide if such a deviation is necessary to comply with Law.[10] The Actuary is required to disclose the nature, rationale and effect of such deviations in accordance with Section 4 of ASOP No. 41, Actuarial Communications.

The Effect of Law on Reporting Under Precept 13

The above is an example of the direct effect that Law has on actuarial practice,[11] not the effect Law might have on the disclosure of an apparent violation of the Code as required by Precept 13.[12] It is reasonable to wonder what aspect of Law could possibly prohibit the reporting of an apparent, material violation of the Code to an appropriate disciplinary body. It may be that this catch-all provision of Precept 13 is designed to emphasize that Law takes precedence over the Code. Or, it may reflect the possibility that an Actuary working as an expert in a lawsuit, for example, may be required by the court (e.g. under a protective order issued by the court) or by attorneys in the case not to disclose information received in connection with a lawsuit.

The discussion above may indicate a loose link between the Precept 13 exception to disclosure in situations where Confidential Information would have to be divulged and a Law or legal requirement to keep such information confidential. That is, Law, in limiting the disclosure of Confidential Information, could prohibit disclosure of an apparent Code violation under Precept 13.

Applicability of Foreign Law or Code

As described in the preamble to the Code, Actuaries are expected to be familiar not only with the Code but also with “applicable Law and rules of professional conduct for the jurisdictions in which the Actuary renders Actuarial Services. An Actuary is responsible for securing translations of such Laws or rules of conduct as may be necessary.”

For example, an Actuary who is a member of any U.S.- based actuarial organization doing work intended to be used in a foreign country needs to comply with the Law and standards applicable to actuaries in that foreign country. If that country’s Law or standards (including qualifications and ASOPs or their foreign equivalent) differ from or conflict with the Code requirements, that country’s Law and standards take precedence with respect to Actuarial Services rendered in that foreign country. Actuaries rendering services intended to be used in foreign countries who do not consider the Law and standards effective in a foreign country may violate those Laws and standards as well as the Code. Remember that no matter where they render Actuarial Services or practice, members of any of the five U.S.-based actuarial organizations are bound to the Code and therefore the jurisdiction of the ABCD (unless a cross-border discipline agreement exists among member organizations within and outside the United States).

Determining whether a potential violation of the Code has occurred is a complex issue in an international context. With potentially multiple sets of applicable Law and standards germane to any such situation, the value of seeking to resolve any apparent, material violation through voluntary discussions with all actuaries involved cannot be overstated.[13]

Impact of ASOPs

ASOPs provide guidance on actuarial practice, but they “are not narrowly prescriptive and neither dictate a single approach nor mandate a particular outcome. Rather, ASOPs provide the actuary with an analytical framework for exercising professional judgment, and identify factors that the actuary typically should consider when rendering a particular type of actuarial service.”[14]

An Actuary’s responsibility when deviating from the guidance contained in an ASOP is addressed in ASOP No. 41, section 4.4. If, in the Actuary’s professional judgment, the Actuary needs to deviate materially from the guidance set forth in an applicable ASOP (excluding certain specific situations addressed in sections 4.2 and 4.3 of ASOP No. 41), the Actuary can still comply with the ASOP in question “by providing an appropriate statement in the actuarial communication with respect to the nature, rationale, and effect of such deviation.”[15] Disclosure by itself however does not provide an “ethical” safe harbor for an actuary if the disclosed work constitutes a violation of applicable laws, rules, regulations, standards, or the Code. (See Appendix B, Example 3.)

Issue: The Impact of Professional Judgment

Deviation from the specific guidance contained in an ASOP may come as the result of the exercise of professional judgment in addition to requirements of Law or regulation.

Therefore, it would be reasonable for an Actuary to consider professional judgment as a factor when reaching conclusions or forming an opinion regarding the processes used or result communicated by another Actuary whose work product is being considered.

| Hypothetical Example Example 5: Internal Reporting Situation A colleague within your consulting firm, an Actuary, is on vacation. One of his clients calls with questions on the report your colleague sent recently. You review the report and answer the client’s questions. However, in reviewing your colleague’s report, it becomes apparent that your colleague violated not only the firm’s procedures but also the Code. Your firm has an internal process for handling such matters, and you report the situation internally in accordance with that process. Two months later, you have heard nothing about your internal reporting. In addition, no new or revised report has been prepared for the client. In following up on your initial inquiry, you are politely told that the matter is still being investigated internally. Do you have an obligation to report your colleague to the ABCD? Does your answer change if your firm tells you that the matter has been resolved internally, even if no subsequent communication has been made regarding the original report to the client? Discussion Precept 13 suggests a process through which apparent, unresolved, material violations of the Code may be resolved by discussion with the Actuary thought to have committed a violation. It may be reasonable to assume that in reporting this possible violation using your firm’s formal, internal process that you have initiated a discussion intended potentially to resolve the matter as suggested by Precept 13. It may also be argued that reporting your suspicions to your employer is not the same as trying to resolve the apparent violation with the other Actuary yourself. In either case, if a resolution is not accomplished, Precept 13 imposes an obligation on you to report the apparent violation to the ABCD, subject to the limitations of Law or the non-disclosure of Confidential Information. Precept 13 does not indicate any timeframe in which to make that report, but common sense dictates you should report it within a “reasonable time” based upon the individual circumstance involved. Your firm’s rules, procedures, and processes do not relieve you of the individual professional responsibility to abide by the Code. If you determine that the matter remains unresolved despite an attempt by your firm’s internal process to resolve it, you may wish to attempt a resolution yourself through a discussion with the other Actuary or you have an obligation to report the apparent, unresolved, material violation to the ABCD. Under the Code you do not need permission from your firm to make a disclosure to the ABCD. Further under the Code, you have no obligation to disclose to your firm that you have made a disclosure to the ABCD. Of course, in considering your obligation to make a disclosure under Precept 13, you should consider whether Confidential Information may need to be disclosed. Keep in mind that the Code is an individual obligation, not a corporate or business obligation. If you are informed that the matter has been resolved internally but no apparent correction to the report in question has been made and you still believe the Code has apparently been violated, you must report the apparent violation to the ABCD under Precept 13. Your reporting the apparent violation to your firm may not satisfy your obligations under Precept 13, and your firm, to the extent that it has addressed the violation of the internal rules, may not have resolved the matter to the extent intended by the Code. Management might, for example, tell you that, subsequent to your identifying the apparent Code violation to them, their review of the report indicated that there was no violation of the Code—giving reasons or justification for this conclusion. Or, they may argue that the error was not material. The indication that the matter was handled internally may only apply to the violation of the firm’s rules, and you may have no right to details on this. If you are convinced by the firm’s explanation, your obligation to report the matter to the ABCD may have been eliminated. |

Professional judgment is defined in section 2.9 of ASOP No. 1. Essentially, the accumulation of specialized training and education (of a basic and continuing nature) with the broader knowledge and understanding that come from experience combine to form the basis for the thoughtful exercise of professional judgment. It is unlikely that all actuaries qualified in a particular practice area would have an identical set of knowledge and experience. The exercise of professional judgment may result in actuaries reaching distinctly different results, outcomes, or conclusions.

A qualified Actuary reviewing the results, outcomes, or conclusions reached in the work product of another qualified Actuary should consider the logic and reasoning underlying any conclusion reached, in whole or in part, through the exercise of professional judgment. The fact that the reviewing Actuary may reach a different conclusion based on the same input does not necessarily indicate that a Code violation has occurred.

Reasonable differences of opinion should be expected (see Precept 10, Annotation 10-3, of the Code).

In some circumstances it is important to remember that different Actuaries may come to different conclusions. Arguments might be made that one conclusion could be given greater weight or authority than the other without discrediting the methods used to reach either.

Actuaries often exercise professional judgment in areas of practice or assignments in which no directly applicable Standards exist. Clearly, where no ASOP exists, violations of the Code cannot be derived from a failure to comply with an Actuarial Standard of Practice although Precept 3 of the Code states in annotation 3-2 “…where no applicable standard exists, an Actuary shall utilize professional judgment, taking into account generally accepted actuarial principles and practices.” Generally accepted actuarial practice may serve as the default guide in practice areas not subject to a formal Standard. Knowledge of generally accepted actuarial practice is, typically, accumulated as a result of relevant professional experience and the pursuit of specialized training. These are key components of professional judgment. Therefore, the appropriate exercise of professional judgment may be related to the reasonable application of acquired knowledge, experience, and specialized training.

Section 2.10 of ASOP No. 1 defines the term “reasonable” in the context of actuarial practice. Whether taking reasonable steps, making reasonable inquiries, or otherwise exercising reason when performing professional services, “the intent is to call upon the actuary to exercise the level of care and diligence that, in the actuary’s professional judgment, is necessary to complete the assignment in an appropriate manner.”

Issue: Reporting on Other Actuaries’ Violations of Precept 13

Precept 13 serves a vital and important role in enabling the self-regulation of the actuarial profession. Actuaries must adhere to the tenets of Precept 13 regardless of how uncomfortable they may feel as a result of having done so. An Actuary with knowledge of an apparent, material violation of the Code that remains unresolved has an obligation to report such actuary to the ABCD, or he or she is in violation of Precept 13, unless Law or the existence of Confidential Information prevents such disclosure.

This situation can arise when an Actuary publicly or privately identifies another Actuary as having violated the Code. Often such assertions are made with enough conviction that it is reasonable to believe that the first Actuary has knowledge of an apparent, material violation of the Code by the second Actuary. When such public or private identifications are not followed with formal disclosure to the ABCD as required by Precept 13, the first Actuary may have in fact violated Precept 13. If the first Actuary later retracts his or her accusation of the second Actuary because the first Actuary learned something that leads him or her to believe that the second Actuary did not violate the Code, then the first Actuary has not violated Precept 13 since Precept 13 requires an Actuary to have actual knowledge of an apparent, unresolved, material violation.

In making a false accusation, however, the Actuary may have violated other Precepts of the Code, for example, Precept 1 (Professional Integrity) or Precept 10 (Courtesy and Cooperation).

Typically, a public forum is not the appropriate venue to air complaints regarding another Actuary’s conduct relative to the Code. Precept 13 provides Actuaries with a way to address concerns of a professional nature. This process begins with a possible private discussion with the Actuary whose work is in question in an attempt to resolve the situation. If that discussion is not attempted or unsuccessful, the next step in the process is to report to the ABCD.

Issue: How to Make a Precept 13 Disclosure

Precept 13 provides no time frame by which disclosures must be made, but it does create a real obligation to make such a disclosure if an apparent, material violation cannot be resolved. The Code preamble states unambiguously: “An Actuary shall comply with the Code.” The Code, unlike an ASOP, makes no provision for deviation. Under Precept 13, knowledge of an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code triggers the obligation to

- Consider discussing the apparent violation with the Actuary whose work is in question in an attempt to achieve resolution; and/or

- If resolution is not achieved or attempted, disclose it to the ABCD, subject to the limitation in Precept 13 that disclosure is not required where such disclosure would be contrary to Law or would divulge Confidential Information.

The ABCD would likely apply a reasonableness rule in determining whether a complaining Actuary has submitted a complaint against a subject Actuary in a timely manner consistent with Precept 13. That is, a reasonable amount of time would be allowed for forming an opinion regarding whether another Actuary has engaged in an apparent, material violation of the Code, for permitting an attempt at resolution through discussion with the other Actuary, and for going through the administrative process of filing a complaint.

ABCD procedures describing the complaint process may be found in the ABCD’s Rules of Procedure.[16] An Actuary who is unsure of his or her Precept 13 obligations is free to use the ABCD Request for Guidance process.

According to the ABCD Web page concerning complaints, a formal complaint “should succinctly describe what the [A]ctuary did (or failed to do) that might be a material violation of the Code of Professional Conduct.”[17] All complaints must be submitted in writing, and, when feasible, should include materials that document the conduct in question. Complaints should be signed by the complainant, who does not have to be a member of an actuarial organization. The ABCD evaluates all formal complaints and information submissions and may or may not choose to escalate the matter for inquiry.

Conclusion

The credentialed actuaries who are members of any of the five U.S.-based actuarial organizations are governed by the Code of Professional Conduct. As members of a self-regulated profession, actuaries have a responsibility to uphold high standards in order to serve the public interest and maintain public confidence in the profession as a whole.

Adhering to all precepts of the Code, especially Precept 13, is a critical component of achieving that professional goal.

Precept 13 creates an obligation for an Actuary with “knowledge of an apparent, unresolved, material violation of the Code by another Actuary” to disclose that apparent violation to the profession’s counseling and discipline body which, in the U.S., is the ABCD.

Appendix A: Precept 13 Process Flowchart

Precept 13: How It Works