By John Divine

Tesla is the rare breed of company that’s hard to define. It’s an automaker, sure—or is it primarily a tech company? Some shareholders even consider it primarily an energy play. But insurer? Only recently can that appellation be thrown into the mix.

The electric vehicle (EV) giant, not exactly known as a conservative, by-the-book corporation—it bought $1.5 billion in Bitcoin to put on its balance sheet in early 2021, recall—is flexing its muscles in the car insurance field.

Although Tesla first entered the car insurance market in 2019, offering policies to its drivers in California,[1] the company’s October 2021 expansion of its offerings to Texas is notable for two reasons. First, it’s a vote of confidence in the business model and a concrete next step in its plan to increase coverage across the rest of the U.S. The company hopes to cover most of the country by the close of 2022.[2] Eventually, it aims to offer insurance coverage in every market in which it currently operates.

Second, and more to the point for the insurance industry at large: Tesla is using real-time driver data to determine its rates in Texas. By using the vast amounts of on-car data that only Tesla can see, the company should have a dramatic pricing advantage over rival insurers.

And if Tesla’s claims are true, it already does. The company states that its rates informed by real-time driving data can save the average driver between 20% and 40%, and the safest drivers would see 30% to 60% lower prices compared to competitors.[3]

Even so, why is this unproven new entrant into the insurance field—whose real-time-data-informed offerings only address a tiny percentage of the overall market in one state—even worthy of legacy insurers’ attention?

The reason: It’s not about Tesla’s market share going from zero to negligible. It’s about technology, and its stubborn tendency to invade, redefine, or otherwise consume other industries. It’s because Tesla’s decision to use real-time data to offer insurance to its drivers in Texas is a harbinger of much, much bigger things to come.

Tesla, Breaker of Molds

In Tesla’s third-quarter 2020 earnings call, management fielded questions from retail investors. One of the most interesting questions concerned what company leadership believed would be the most valuable business units—outside of electric vehicles—within Tesla over the coming five to seven years.

In his answer, CEO Elon Musk was remarkably bullish on one segment of the business:

“Obviously, insurance is substantial. So insurance could very well be, I don’t know, 30%, 40% of the value of the car business, frankly.

“And as we’ve talked about before, with a much better feedback loop, instead of being statistical, it can be specific. And obviously, somebody does not have to choose our insurance. But I think a lot of people will. It’s going to cost less and be better, so why wouldn’t you?”[4]

This confidence was echoed a year later, in shareholder materials accompanying Tesla’s Q3 2021 quarterly update. The deck was 27 slides long, but all it took was one sentence to glean the company’s outlook on its new insurance product.

“We believe our insurance premiums will be able to more accurately reflect chances of a collision than any other insurance product on the market,” the company wrote.[5]

What, exactly, gives Tesla such remarkable conviction?

Safety score, pricing methodologies, and telematics

The crux of Tesla’s car insurance pricing is an internal company metric called the safety score.

There are five components to a driver’s safety score, each of which is measured by on-car sensors and Tesla’s proprietary Autopilot software:[6]

- Forward collision warnings per 1,000 miles. These alerts are given to drivers in cases where the car could hit something in front of it if the driver doesn’t intervene.

- Hard braking. This variable measures how frequently a driver rapidly decelerates when Autopilot is not engaged.

- Aggressive turning. The safety score will be negatively impacted every time left/right acceleration exceeds a certain level and Autopilot is not engaged.

- Unsafe following. By measuring your vehicle’s speed, the speed of the vehicle in front of yours, and the distance between the two cars, Tesla keeps tabs of when its drivers are following other cars too closely.

- Forced Autopilot disengagement. When Autopilot is engaged, Tesla vehicles will give audio and visual warnings to drivers when they remove their hands from the wheel. After three such warnings in one trip, Autopilot will forcibly disengage.

This safety score program is designed not just to reflect levels of risk for different drivers, but also to encourage safer driving. It does this by offering data-based feedback to Tesla customers on what they did well and what they struggled with during their trips, offering specific tips on how they can improve their safety score going forward.

By offering this feedback, the company aims to encourage a feedback loop that begets safer and safer driving habits.

In Tesla’s Q3 2021 earnings call, Chief Financial Officer Zach Kirkhorn spoke briefly about the early days of the safety score program, which at the time was being used by almost 150,000 cars and incorporated more than 100 million miles of driving data.

Kirkhorn said that there were two takeaways from this early rollout of its scoring system:

“The first is that the probability of collision for a customer using a safety score versus not is 30% lower. It’s a pretty big difference. It means that the product is working and customers are responding to it.”

That seems to suggest the early program is meeting one of its goals—namely, to encourage safer driving. What about the score’s predictive ability? Kirkhorn elaborates:

“The second thing that we’ve looked at is: What is the probability of collision based upon actual data as a function of a driver safety score?

“And that is aligning with our models. Most notably, if you’re in the top tier of safety compared to lower tiers, there’s multiple X difference in probability of collision based upon actual data.”[7]

Of course, these reported achievements in safety and predictability only matter to the wider insurance industry insofar as they inform more competitive pricing. And that’s exactly how Tesla intends to use the safety score, with better safety scores bringing down an individual’s monthly premium.

It’s a double-edged sword: As a person’s safety score worsens, their premiums go up, with premiums fluctuating from month to month based on the metric.

This meritocracy in auto insurance provides policyholders with powerful, measurable, and monthly incentives to drive responsibly in the form of lower premiums. And if safer drivers can really save up to 60% on their insurance as Tesla claims, the company will be able to insure all the lowest-risk customers, and incent higher-risk drivers to flee to legacy insurers with far less data than Tesla—insurers that may be underpricing that driver’s risk.

In that scenario, Tesla not only scoops up the desirable safe drivers, but makes rival insurers the victims of adverse selection.

Motivations for Tesla to offer its own insurance product

Aside from the growing corporate belief that unmonetized data is a crime against shareholders, there are a number of reasons car insurance is a natural vertical for Tesla to enter:

- Safety: Tesla prides itself on building safe vehicles, with a number of its models winning acclaim from Consumer Reports, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety[8] and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.[9] In Tesla’s case, if drivers follow its data-based feedback on how to handle their vehicles more safely, the brand will gain even more boasting power.

- Affordability: Another integral part of Tesla’s identity is its long-term plan to bring affordable all-electric vehicles to the masses. It has succeeded in part, but its cheapest model, the Model 3, still retails for $45,000 without incentives,[10] so saving a buck for its customers is still an uphill battle.

Here’s Tesla CFO Kirkhorn again on the Q3 2021 earnings call:[11]

“Our customers were coming to us, complaining that the price of traditional insurance was too high and it was reducing the affordability of a Tesla. And part of our journey here at Tesla is we want as many people as possible to be able to afford our products.

“If you look at the price of insurance as a percentage of what somebody’s monthly payment is, it’s quite high. … The leverage of improving insurance cost is huge in terms of affordability.

“We’re excited about individual risk-based pricing. We’re excited about the ability for folks to become safer and, as a result, save money.”

- Upselling: As with any other auto insurance policy, there’s opportunity to bundle this product with others. For its customers, the EV leader already offers insurance for non-Tesla vehicles.[12] The company also offers some obscure coverage as a part of its Vehicle Automation Package, including autonomous vehicle owner liability, wall charger coverage, and several others.[13]

Importantly, however—and unlike traditional insurers—Tesla doesn’t have to use its insurance policies to sell yet more insurance. In fact, the company reportedly plans to tie insurance discounts to its full self-driving upgrade. This feature costs either $10,000 outright or $199 per month,[14] and, as a software update, is tremendously high-margin. Traditional insurers simply can’t compete, profit-wise, with that type of promotion.

Zooming out from Tesla specifically, car companies in general have natural incentives for entering the business, especially today. In the era of connected cars, new vehicles are shipped with increasingly sophisticated software, GPS technology, and sensors that just so happen to be perfect tools for pricing insurance.

And let’s not pretend Tesla is the only automaker with incentives to enter the auto insurance space. Car companies have many reasons to insure their own vehicles. The ability to direct consumers to their own service centers for repairs, keep the cost of ownership down by offering fair policy premiums, and the potential to bundle car insurance with other insurance or subscription offerings all come to mind.

Insurers’ driver-tracking apps

Now, it’s not like Tesla invented the idea of tracking how you drive in order to price insurance. Insurance trackers originated with dongles that plugged into your car and have evolved to mostly become apps.

Most of the major car insurers in the U.S. have usage-based insurance (UBI) programs that do exactly this, with tracking systems required for those drivers.

Here are some of the many programs intended to track driver behavior[15] at leading insurers:

- Allstate: Drivewise

- American Family: KnowYourDrive

- Farmers: Signal

- Geico: DriveEasy

- Nationwide: SmartRide

- Progressive: Snapshot

- State Farm: Drive Safe and Save

- Travelers: IntelliDrive

- USAA: SafePilot

Progressive’s Snapshot program is the oldest of the bunch, dating all the way back to 1998.

And in 2013, when these UBI apps had begun to pop up, the Oracle of Omaha Warren Buffett himself opined on the use of driver-tracking programs to price insurance. At the time, Buffett didn’t seem especially anxious to prioritize the development of such programs in Berkshire Hathaway’s Geico business.

At Berkshire’s annual meeting that year, a shareholder asked whether Geico still had no plans to adopt usage-based driving tech, specifically referencing rival Progressive’s Snapshot program.[16], [17] The shareholder wondered: “Why wouldn’t that technology give Geico better data to potentially give discounts to customers?”

Buffett downplayed the technology in his answer:

“Yeah. That [Geico’s decision to steer clear of usage-based tech] still is the case, and Snapshot has attracted a fair amount of attention and there are other companies doing that. It’s an arrangement, essentially, to tie—well, the term ‘Snapshot,’ perhaps, says it—to get a picture of how people really do drive. Insurance underwriting, you know, is an attempt to figure out the likely propensity, based on a number of variables, of a person having an accident.

“When you get into auto insurance, figuring out who’s likely to have an accident involves assessing a number of variables, and different companies go at it different ways. … We ask a number of questions, and our attempt, as much as possible, is to figure out the propensity of any given applicant, or the possibility, that they will have accidents.

“And there are a number of variables that are quite useful in predicting. And Progressive is focusing on this Snapshot arrangement, and we’ll see how they do. I would say that our ability to sell insurance at a price that’s considerably lower than most of our competitors, evidenced by the fact that when people call us, they shift to us, and, at the same time, earn a significant underwriting profit, indicates that our selection process is working quite well. …

So our systems, our underwriting criteria, have been developed, you know, over many decades. We have a huge number of policyholders, so that it becomes very credible, these different underwriting cells. And everybody in the business is trying to figure out ways to predict with greater accuracy the possibilities that a given individual will have an accident. And Progressive is focusing on this Snapshot approach, and we watch it with interest, but we’re quite happy with the present situation.”

And watch Berkshire did. It watched Progressive’s Snapshot and other similar programs for six additional years after that Q&A before finally entering the telematics space with its DriveEasy app in 2019.[18]

Tech’s Growing Influence on Insurance

Just because leading insurers have been in the driver-tracking game for years—and some, like Progressive, for decades—doesn’t mean they’ve mastered the practice.

Take Berkshire Hathaway, whose chairman and CEO Warren Buffett has a legendary track record as a manager and capital allocator. Between 1964 and 2020, Berkshire shares returned 2,810,526% versus the S&P 500’s 23,454% return.[19]

Although Buffett was well aware of the usage-based technology in car insurance in the early part of the 2010s, the company and its subsidiary, Geico, has uncharacteristically not executed well on the long-extant opportunity. Remember: In 2013, Buffett noted that the company had no plans to adopt usage-based driving technology or telematics, the long-distance transmission of computerized data. It didn’t even enter the business until 2019.

Here’s Ajit Jain, vice chairman of insurance operations, at Berkshire’s 2021 annual meeting, on playing catch-up in telematics:

“Geico had clearly missed the business, and were late in terms of appreciating the value of telematics. They have woken up to the fact that telematics plays a big role in matching rate to risk. They have a number of initiatives, and, hopefully, they will see the light of day before, not too long, and that’ll allow them to catch up with their competitors, in terms of the issue of matching rate to risk.”[20]

The company Berkshire clearly views as Geico’s biggest competition in auto insurance is Progressive, which Jain noted enjoyed margins almost twice as high as Geico’s in 2020. And Buffett himself, who struck a dismissive tone in 2013 and confidently bragged about Berkshire’s ability to price risk, has changed his tune. At the 2021 shareholder meeting, he admitted that Progressive had been better at setting the right rate.

It’s tempting to chalk Berkshire’s shortcomings in telematics up to Buffett’s own famous aversion to, and poor understanding of, technology. But this issue isn’t specific to Buffett or Berkshire. The insurance industry at large is at a crossroads. Technology, more and more, is both an opportunity and a threat.

Insurtech

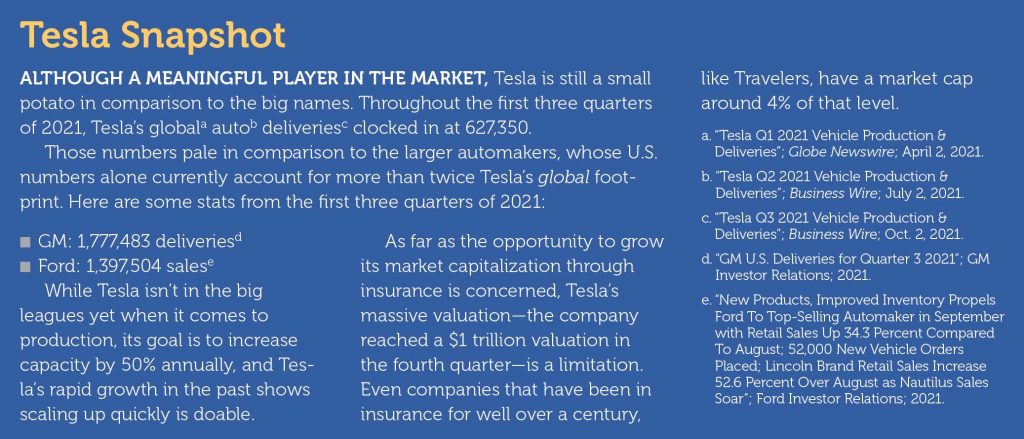

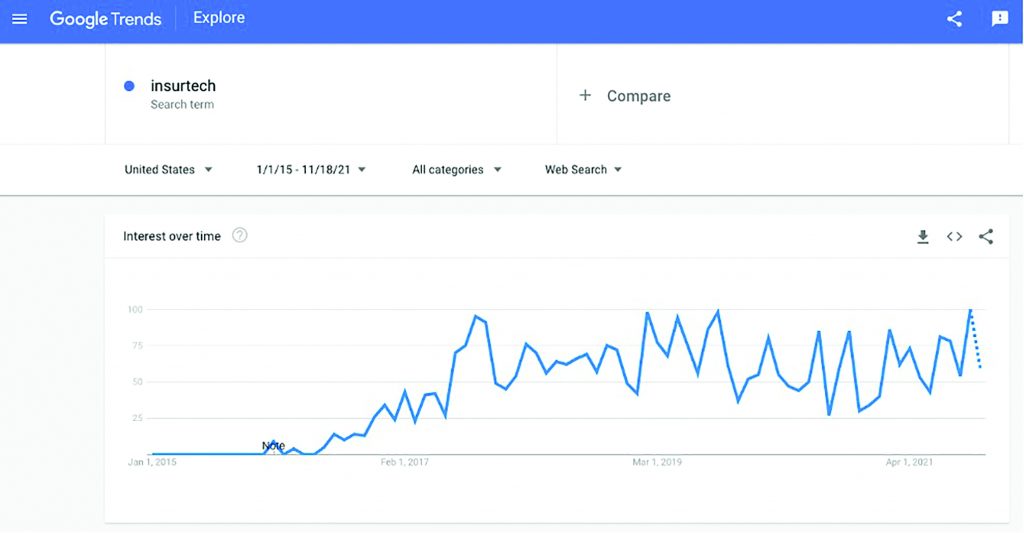

The convergence of insurance and technology is so rampant that it’s spawned its own portmanteau, “insurtech,” a term that essentially didn’t exist as recently as 2015 if data from Google Trends is to be believed.

By 2017, the term had garnered enough traction to be used in Forbes headlines[21] and McKinsey reports.[22]

That rapid growth is expected to continue in the years ahead, and, like the broader technology sector, insurtech was given a massive growth spurt by the COVID-19 pandemic as the digital economy subsumed the physical, work-from-home policies proliferated, and the transition to the digital economy accelerated wherever opportunity presented itself.

A recent report from Allied Market Research forecast a compound annual growth rate of 32.7% for the insurtech space from 2021 to 2030, as the size of the market balloons from $9.4 billion to $159 billion.[23]

The technology and insurance marriage is a coming together of two natural partners. Insurance might be said to be naturally concerned with big data, a domain that in today’s age is itself almost exclusively associated with the technology sector, artificial intelligence, and machine learning.

Current and future competition

Point being, Tesla is just a drop in the bucket when it comes to nontraditional market participants encroaching on the insurance field.

Arguably the most prominent insurtech player today is Lemonade, a company founded in 2015 and built from the ground up to disrupt. It went public in 2020, quickly garnering a market cap above $3 billion.

Lemonade offers renters, homeowners, pet, life, and—as of November 2021—car insurance. In its founders letter, the company lays bare its goal to become the “preeminent insurance brand of the next century,” outlining principles like:[24]

- Being “short term patient, but long term greedy.” Lemonade unapologetically promises to aggressively increase market share and expand its geographical footprint at the expense of short-term gains, where it sees the upfront cost as justifying longer-term staying power.

- “We are risk takers, not thrill seekers.” The founders write that they prefer to make decisions in times of uncertainty to seize potential opportunities, only abandoning endeavors when data proves them unwise.

- An explicit rejection of short-term share price fluctuations as meaningful signals.

- “We believe values add value.” Lemonade is the world’s first insurer to also be a Public Benefit Corporation,[25] which means the company is legally obligated to consider stakeholders other than shareholders in its decisions.

Ironically, Lemonade’s steadfast focus on long-term opportunities and rejection of day-to-day stock price fluctuations sounds a lot like the principles that guide Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway. The similarities, however, end there.

Firstly, Lemonade takes a flat rate for itself, and, in line with its social mission, donates the remainder of the premiums to causes chosen by its policyholders. Berkshire, on the other hand, wouldn’t be caught leaving a nickel on the table.

Moreover, rather than eschewing technology and sitting on the sidelines to see how competitors do, Lemonade is diving headfirst into what it views as the right way to take care of its policyholders, using AI-driven chatbots and a mobile-first ecosystem to cut out brokers and streamline everything for customers. “Zero paperwork and instant everything”[26] is the goal.

The differentiated philosophy seems to be working: Lemonade’s mobile app has a 4.9-star rating on the Apple App Store, better than Geico, Progressive, Allstate, Liberty Mutual, State Farm, American Family, Farmers, Nationwide, Travelers and USAA.

It’s hard to argue with the convenience: The mobile-first approach allows customers to get insured from their phone in as little as 90 seconds, and get paid out on claims in three minutes, according to the company website.[27]

And from a revenue perspective, Lemonade is also a hit, with the top line in the third quarter of 2021 surging 101% year over year. That, too, is the sort of growth the aforementioned competitors can only dream about.

Critics will correctly strike at the most obvious weakness of Lemonade, which is that the company is profoundly unprofitable and has a small market share. On $35.7 million of revenue in Q3, Lemonade lost $66.4 million.[28] That said, the company has been transparent about its willingness to rack up big losses in the early innings to invest in growth and expand market share.

Other insurtech names on the cutting edge of the industry include:

- Fitsense. This company uses wearables to inform health and life insurance quotes and policies.

- Roost. Roost uses smart home technology for loss prevention in the field of property insurance.

- Steppie. Steppie combines aspects of both Roost and Fitsense: It uses “lifestyle data” from wearables to reward customers for healthy behaviors in an effort to prevent claims.

- Cuvva. Like Lemonade, Cuvva is an insurtech company designed with mobile in mind, intended to be extremely fast and easy to interact with. Unlike Lemonade, Cuvva focuses on car insurance and will insure users on an ad hoc basis for as long or as briefly as they like—even if it’s only an hour.

- Slice Labs. Using big data, Slice Labs prices insurance on an on-demand, as-needed basis. For instance, the company will price policies for ride-share drivers on a pay-per-use model.[29]

Future threats, and the trade-off between privacy and price

The moment new entrants in the insurance field start providing real discounts to policyholders in exchange for more data—and such entrants do so profitably and en masse—the free-market tug-of-war between lower premiums with less privacy and higher premiums but more privacy will begin.

You don’t need a crystal ball to tell which side will come out victorious in that battle. A quick glance at consumer behavior in the 21st century tells you all you need to know.

Only six companies have ever reached a $1 trillion valuation on U.S. exchanges. Two of them, Facebook and Alphabet (Google’s parent company), were built entirely on the premise that consumers will trade away their data for nonmonetary benefits.

When consumers are presented with a clear option of whether they’d like to sacrifice data privacy for cold, hard monetary benefits in the form of lower premiums … well, it doesn’t take an actuary to tell that the odds heavily favor the low-premium, low-privacy side winning out here.

Why can’t existing insurers offer both, and let the customer choose? They certainly can—and indeed, many of them do—but the problem lies in the ability of traditional insurers to collect enough unique high-quality data to profitably offer discounts. Progressive, for example, can’t track forward collision warnings, monitor unsafe following or incorporate forced Autopilot disengagement into actuarial tables like Tesla does. There isn’t an app for that.

And this is where things get scary for incumbents.

What might be

One can easily envision a future where wearables companies leverage their market share and consumer brand recognition to parlay into health care. Both Alphabet, which owns Fitbit, and Apple via its Apple Watch, are trillion-dollar-plus software companies with practically endless resources and ambition. Neither is afraid to employ a little disruption in service of the bottom line.

What if Google and Apple decided to use this wearables data to enter health insurance themselves? As with Tesla, no rival insurer would be able to collect the sort of data directly relevant to pricing policies—data like daily activity, fall detection sensors for seniors and heart arrhythmia monitoring.[30]

This hypothetical isn’t all that pie-in-the-sky, especially considering that major insurers Aetna and United Healthcare had already confirmed the utility of Apple Watch’s unique data as far back as 2016[31] and 2018,[32] respectively—the year each insurer first began offering subsidies for the watch.

By 2019, both insurers were already offering senior citizens subsidies for buying the Apple Watch due to its health care insights. Moreover, Apple CEO Tim Cook has said that in the future, people will look back and say, “Apple’s most important contribution to mankind has been in health.”

It’s not just health care and car insurance where the potential for disruption exists. Property insurance—particularly homeowners insurance—could be shaken up by the internet of things and smart home companies, should they choose to enter the field.

Offering discounts on homeowners insurance premiums is already a widespread practice in the industry, with haircuts between 5% and 20% fairly par for the course.[33] Even more insurers have programs that subsidize the purchase of certain smart home devices themselves, including smart thermostats, security systems and sensors, the Amazon Echo Dot, gas and water shutoff sensors, and of course smoke detectors.

The smart home arena is also bustling with multiple trillion-dollar companies: Alphabet owns the Nest line of smart home devices, Amazon has its Alexa-enabled devices and Ring security systems, and a long list of connected products work with Apple HomeKit.

If it’s already worth it for insurers to subsidize smart home products and offer premium discounts, at what point will these tech behemoths decide the same trade-off makes sense for them? Once these companies have enough market share—which insurers are helping to expand through subsidies—who’s to say Amazon doesn’t start offering homeowners insurance itself, offering subsidies for anyone who buys Amazon insurance? The company is notorious for seeing how certain products sell on its own site and then making its own version of the product and destroying the original innovators.

A 2020 study from LexisNexis Risk Solutions showed that 78% of smart home device owners are willing to share data with their insurers to help price their policies, although 65% of smart home device owners would only share their data with insurers in exchange for discounts.[34]

‘If You Can’t Beat ’Em, Join ’Em’

Though it’s an insurance company, Lemonade has been built from the ground up on the premise that technology and insurance are now inseparable—and the company is moving with the speed of a startup in its pursuit of market share. In November 2021, Lemonade made three moves in a matter of weeks that signified its ambitions to scale rapidly.

It hired Sean Burgess, a more than 25-year veteran of USAA who had served as senior vice president and chief claims officer, as chief claims officer at Lemonade.[35] And within a matter of days it entered the car insurance market in the U.S. and announced the acquisition of Metromile, a digital insurance platform that prices insurance by the mile based on driver behavior.[36]

Lemonade also makes a cogent point in its explanation for its pursuit of Metromile, noting that investing in real-time driver data now gives the company an advantage that will only compound over time as the use of certain proxies for risk—like credit score, gender, education and so on—are increasingly disallowed from being used in insurance pricing by state regulators.

Travel agents, booksellers, tax professionals, print media, taxis, cashiers—if legacy insurers don’t want to join the long list of industries and professions turned on their head by technology, it may be time to start aggressively pursuing some M&A of their own.

The Bottom Line

Tesla’s entry into auto insurance is emblematic of the changing, more technological, and increasingly competitive insurance landscape.

It shows the competition from two sides—from automakers themselves, and from tech companies—that’s looming. (Tesla just happens to be both.)

In today’s day and age, virtually nothing is more valuable than data, and with the spread of the internet of things, the insurance field is uniquely vulnerable to new competitors, largely coming from the firms behind the devices and software that collect live, real-world, comprehensive usage stats organically—in a way that traditional insurers can’t.

One 2017 quote from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos seems eerily relevant here:

“We know that customers want low prices, and I know that’s going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

“It’s impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, ‘Jeff, I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher.’ ‘I love Amazon; I just wish you’d deliver a little more slowly.’ Impossible.”[37]

These observations are true across sectors, across industries, and across time. And if legacy insurers can’t harness technology to price more fairly and make customer interactions more seamless, they will be in for a rude awakening.

JOHN DIVINE is a freelance writer based in Charlotte, N.C.

References

[1] “Tesla launches its own insurance program, claims up to 30% cheaper”; electrek; Aug. 28, 2019. [2] “Tesla Insurance expands to Texas next week , ‘aspirationally’ most of the US next year”; electrek; Oct. 8, 2021. [3] Ibid. [4] Ibid. [5] “Q3 2021 Update”; Tesla; Oct. 20, 2021. [6] “Safety Score Beta”; Tesla; 2021. [7] “Tesla (TSLA) Q3 2021 Earnings Call Transcript”; The Motley Fool; Oct. 21, 2021. [8] “Tesla Model 3 Gets Back its Safety Awards”; Kelley Blue Book; June 30, 2021. [9] “Model Y Achieves 5-Star Overall Safety Rating from NHTSA”; Tesla; Jan. 13, 2021. [10] “Design Your Model 3”; Tesla. [11] “Tesla (TSLA) Q3 2021 Earnings Call Transcript”; The Motley Fool; Oct. 21, 2021. [12] “Tesla Insurance”; Tesla. [13] “How Much Does Tesla Insurance Cost? How Does the Price Vary by Model?”; ValuePenguin; Dec. 7, 2021. [14] “Car Insurance: When Google Shrugged”; Strategy Analytics; April 12, 2021. [15] “How Do Those Car Insurance Tracking Devices Work?”; U.S. News & World Report; Aug. 27, 2021. [16] “Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Meeting Transcript – 2013”; Dropbox. [17] Ibid. [18] “Berkshire Hathaway’s GEICO launches first telematics program”; Reinsurance News; July 31, 2019. [19] “Berkshire Hathaway 2020 Annual Report”; Berkshire Hathaway; Feb. 27, 2021. [20] “Ajit Jain on Where GEICO Has Gone Wrong in Recent Years”; Yahoo!; May 14, 2021. [21] “NYC Emerges As The Capital Of Insurtech”; Forbes; Aug. 30, 2017. [22] “Insurtech—the threat that inspires”; McKinsey & Company; March 1, 2017. [23] “Insurtech Market to Garner $158.99 Bn, Globally, by 2030 at 32.7% CAGR: Allied Market Research”; PR Newswire; Aug. 17, 2021. [24] “Our Lemonade Stand: A letter from our cofounders”; Lemonade. [25] “World’s Only Public Benefit Insurance Company”; Lemonade. [26] “Lemonade Inc. – Hey investors, welcome home!”; Lemonade. [27] “Insurance Built for the 21st Century”; Lemonade. [28] “Q3 2021 Shareholder Letter”; Lemonade; Nov. 8, 2021. [29] “Lemonade & 12 more insurtech companies you should know in 2021”; Insider Intelligence; July 26, 2021. [30] “Do You Really Want Your Insurer Buying You An Apple Watch?”; Forbes; Jan. 16, 2019. [31] “Aetna insurance will subsidize the Apple Watch”; CNN Business; Sept. 28, 2016. [32] “A giant insurer is offering free Apple Watches to customers who meet walking goals”; CNBC; Nov. 14, 2018. [33] “Smart home insurance discounts”; Bankrate; June 4, 2021. [34] “New IoT Study From LexisNexis Risk Solutions Reveals 78% of Smart Home Device Owners Are Open to Sharing Their Data With Insurers”; PR Newswire; Feb. 12, 2020. [35] “USAA’s Chief Claims Officer Joins Lemonade”; Business Wire; Nov. 18, 2021. [36] “Lemonade to Acquire Metromile”; Lemonade; Nov. 8, 2021. [37] “20 Years Ago, Jeff Bezos Said This 1 Thing Separates People Who Achieve Lasting Success From Those Who Don’t”; Inc.; Nov. 6, 2017.