By Ivan J. Houston with Gordon Cohn

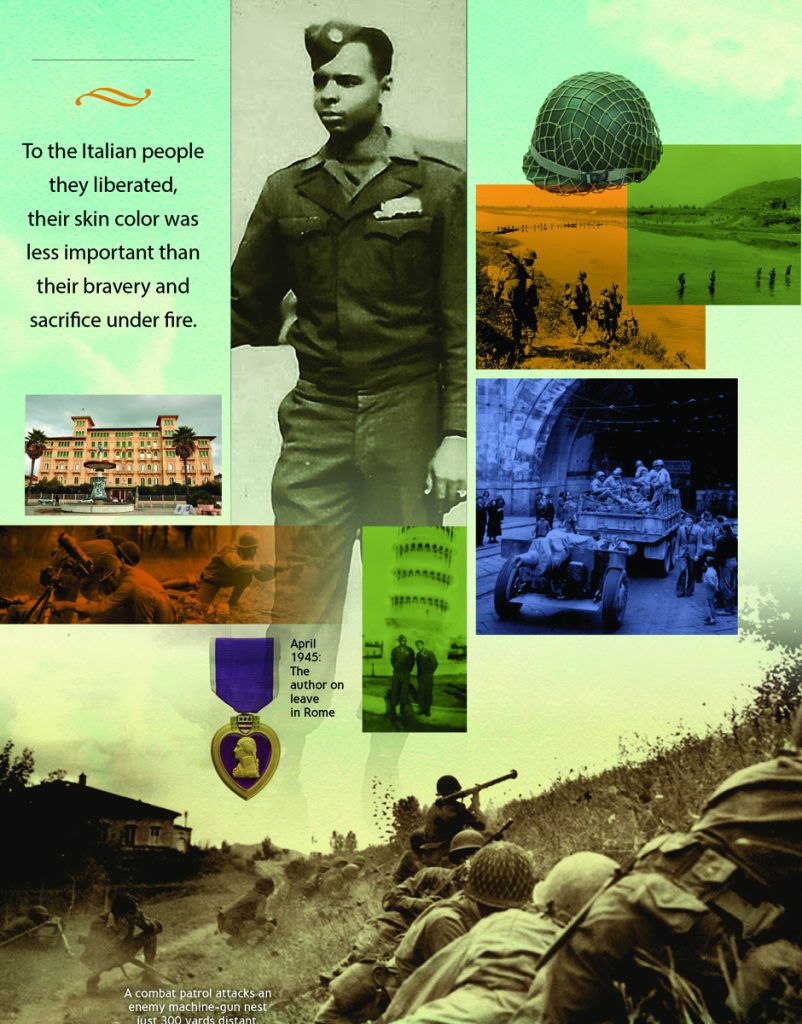

Editor’s Note: Academy member Ivan J. Houston enlisted in the U.S. Army at the age of 17 in 1943 and served as a member of Combat Team 370 of the 92nd Infantry Division of the U.S. 5th Army. Also known as the Buffalo Soldiers, it was the only African-American division to fight in Europe during World War II. Houston, who was chief executive officer of Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Co. from 1970 until his retirement in 1990, wrote about his experiences as a Buffalo Soldier in his book, Black Warriors: The Buffalo Soldiers of World War II (iUniverse, 2009). What follows is excerpted from that book. Houston died this year at the age of 94. Contingencies is republishing this piece, originally published in May/June 2014, in his memory.

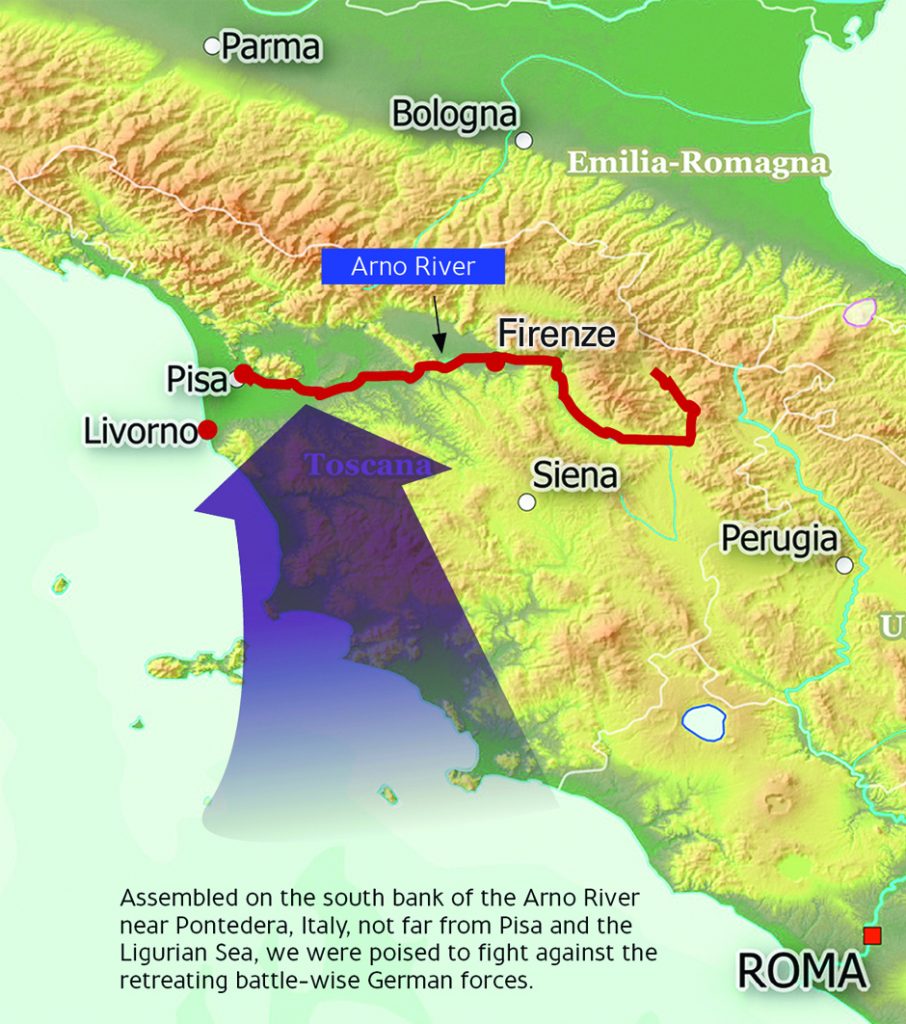

No surviving member of Combat Team 370 of the 92nd Buffalo Division will ever forget Aug. 23–24, 1944, the night we prepared to enter combat for the first time. Assembled on the south bank of the Arno River near Pontedera, Italy, not far from Pisa and the Ligurian Sea, we were a single untested African-American infantry regiment in a racially segregated U.S. Army, poised to fight against the retreating battle-wise forces of Germany’s 16th Panzergrenadier Reichsfuehrer Division under the overall command of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring. Once Hermann Göring’s deputy, “Smiling Albert” had commanded Germany’s air fleets during the invasion of France and the Battle of Britain in 1940 and later served as Gen. Erwin Rommel’s co-director of Germany’s North African campaign. Acknowledged as one of the ablest strategists in the German high command, Kesselring was in Italy to direct a last-ditch defensive effort for a dying army. The Germans had lost Rome to the Allies just 60 days before and had retreated north to a deeply fortified position known as the Gothic Line; this position stretched 170 miles from the Ligurian Sea east across the Apennine mountains that form the spine of Italy to the Adriatic.

Our objective as the 370th Regimental Combat Team was to cross the Arno River and break through the Germans’ Gothic Line, Field Marshal Kesselring’s last major line of defense in northern Italy.

The move to the front through small villages was quite emotional. The Italians knew we were going to fight the dreaded Germans and that some of us would not come back. They threw flowers at our vehicles. They handed flowers and wine to those of us riding in the vehicles.

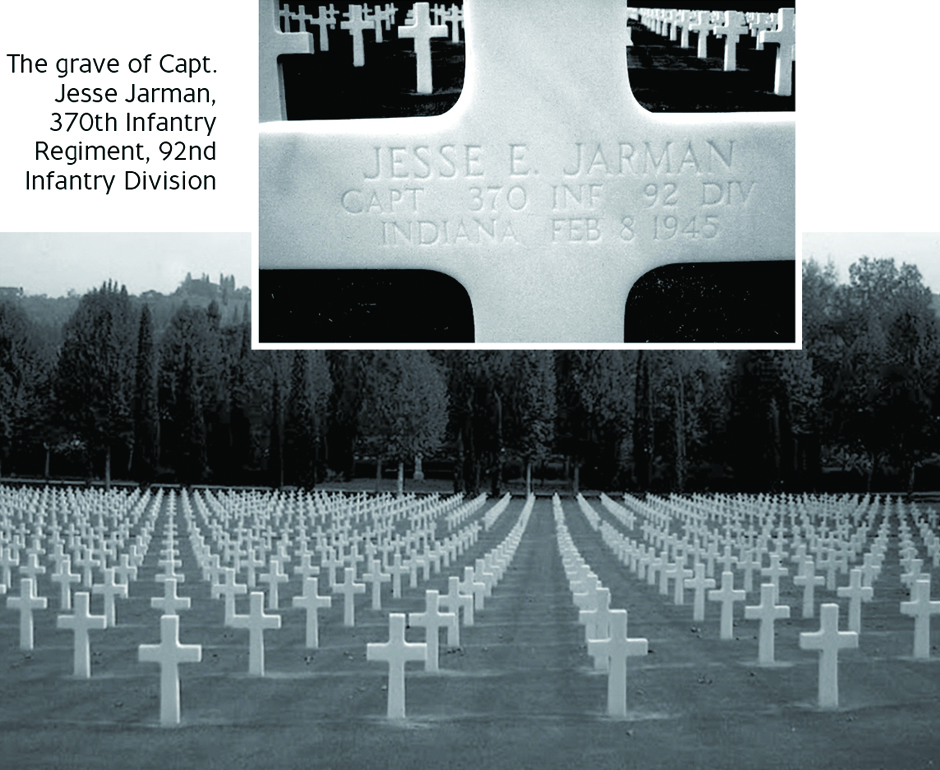

Company I, under its commander, Lt. Jesse Jarman, on the left, with its command post at Cascina, reported enemy activity around an area designated Outpost 4. In the firing that followed, Platoon Sgt. James E. Reid of Company I, with whom I had played cards and passed idle hours only days before as we crossed the Atlantic, was wounded and later died, thus becoming the first fatality of the 3rd Battalion, the first battle casualty of the 92nd Division, and the first African-American in the European theater of war to die in infantry combat. Just like that, someone I had known was gone. There was much confusion during our first night in combat. A password to be used each night was given to every member of the 5th Army, but an American woman named Mildred Gillars, who broadcast German propaganda to the American troops each night as Axis Sally, also had the password somehow. Her revelations enabled the Germans to infiltrate American positions. Axis Sally was to play music for us every night—jazz—and if the Germans had taken any prisoners from our unit, she was certain to announce it. She would say things like, “Give up your arms,” and “Why are you fighting?” We found her jabber entertaining, never demoralizing.

Viva Americani!

On Sept. 1, 1944, Combat Team 370 crossed the Arno River, which flows between Pisa, with its famous leaning tower, and the Renaissance city of Florence.

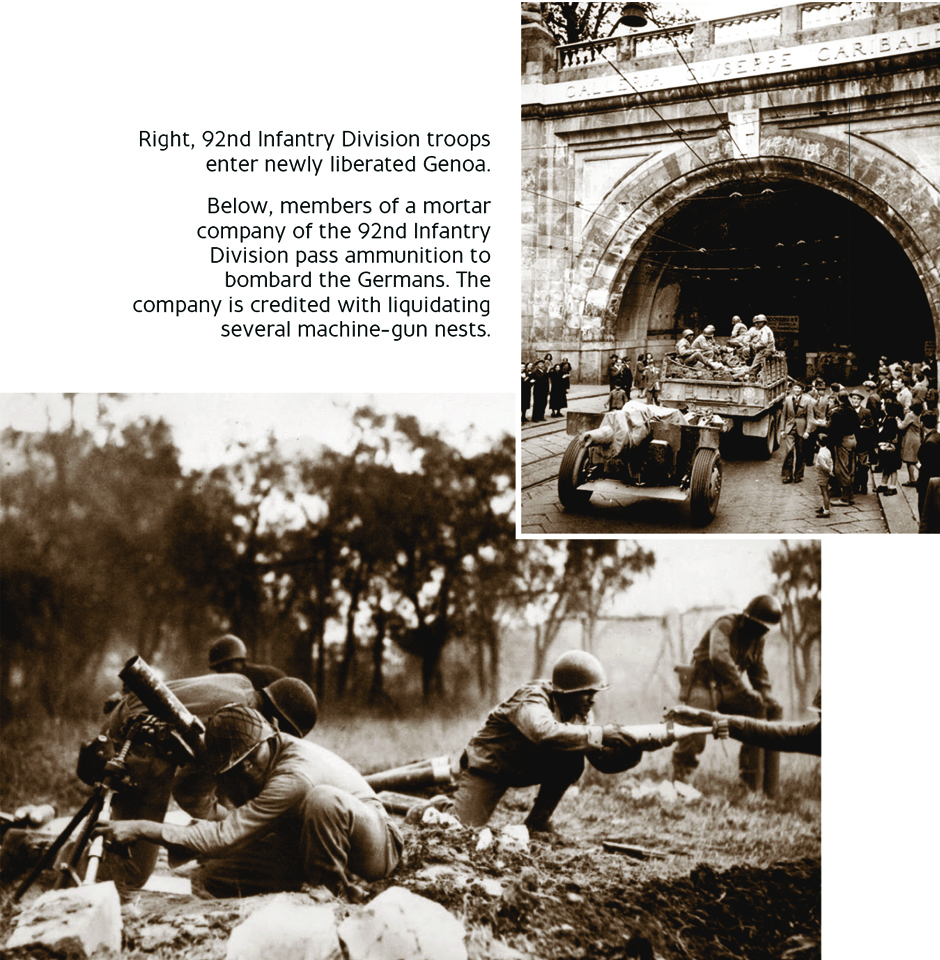

As the 3rd Battalion began its offensive, we moved through the villages and towns of Lugnano, Uliveto, Caprona, and Asciano, all on the north side of the river east of Pisa. All along the way, hundreds of starving and cheering Italians surrounded our vehicles. They threw flowers at us and shouted, “Viva Americani!” They had been living behind German lines for months without adequate food. Even though they were allies of the Germans, they did not like the Tedeschi, the Italian word for Germans. Except for a few fascists, most of the people we encountered were truly happy to see us: They were free. Celebrations in each community seemed to grow as the morning progressed. At a hamlet just north of the Arno, the citizens greeted us with more cries of “Viva Americani!” “Buongiorno!” and phrases that were beyond our limited vocabulary. Others just waved happily. Some of the women could be seen crying. The excited civilians clung to our vehicles and showered the soldiers with grapes, flowers, and fruit. Some ran along, pouring wine for all who would accept it, while others of both sexes and all ages paid their tribute with hearty kisses. They had every guy in the column feeling like a conquering hero. Even today I smile and feel good when I recall those scenes. Here were white Italians greeting African-Americans as liberators and showering us with love, while in our own country we remained second-class in all respects.

It was during the assault on Ripafratta on Sept. 4 that we learned that the noise and dust generated by our tanks were the cause of the heavy German fire. Infantrymen learned to stay away from our advancing tanks. As soon as our tanks appeared, we knew that we had to get some shelter because the Germans were going to start firing at the tanks. They could hear them from a considerable distance or probably see their dust. All kinds of artillery would come flying in if a tank was anywhere near us. This created a dilemma for those troops attacking with tanks since tanks and infantry attacked as a team. The death of Maj. Aubrey Biggs, the executive offer who was with Company I as it assaulted Ripafratta, was a consequence of this kind of teamwork. Major Briggs was the first white officer killed in battle. Also, during the battle for Ripafratta, Jumbo Joe Fry, 1st sergeant of Company K, showed outstanding leadership and later received a battlefield commission. Fry was from Pennsylvania.

Our entire battalion felt the weight of enemy artillery fire that day. We took more than 500 rounds. I don’t think there was an hour that passed from the time we went on line in August until the war ended when there was not artillery fire coming in or going out. We could always hear the artillery passing overhead and the hissing of the incoming shell. Then, of course, there was the explosion, and sometimes when it was close we could feel the debris from it. Mortars were different: You never knew where they were coming from. They would just start exploding around you. My father had been an officer in the 92nd Division artillery in France during World War I. He had told me that artillery fire overhead sounded like a freight train. He was right.

I was in the temporary command post in a very large villa when we were shelled 127 times (I counted), hits and near misses, by German artillery. Two very large rounds from German 11- or 15-inch railroad guns at Punta Bianca, a few miles to the northwest, fell on the soft ground in front of the house but did not explode. When the shelling stopped, I went outside and saw the cylindrical holes the shells had created. Had they exploded, everyone inside would have been killed.

By 0900 hours a handful of brave men of Company L fought their way uphill to the castle. One of them, Sgt. Charles “Schoolboy” Patterson of Fort Wayne, Ind., rushed from cover, throwing hand grenades. He tossed a grenade into a machine-gun emplacement and then snatched a German machine gun from the site. Two other guns were destroyed, but fire was still coming from above the castle. Company K could not assist because they were pinned down by five machine guns hidden in deep emplacements on the crest of the hill. Patterson, who won a Silver Star for his gallantry, was an ASTP alumnus, the Army Specialized Training Program that sent enlisted men who scored high on the Army’s General Classification Test back to college to become engineers, doctors, etc. The army stopped this program in March 1944, sending all of us to infantry divisions. After the war, Patterson moved to the San Francisco–Oakland area and became a successful businessman.

The next day a company of Brazilians arrived, and after a linguistic tangle that involved everyone in the command post, we agreed—in English, Portuguese, Italian, and Spanish—that this company would relieve Company K.

Relief by the Brazilians was almost comic. I was the only member of the battalion headquarters staff who spoke some Spanish and a little Italian. The Brazilian commander spoke a little Spanish, a little Italian, and Portuguese. The Brazilian commander and I talked and finally clarified our situation.

Mounting Casualties

The 3rd Battalion had succeeded in breaching the famed German fortifications of the Gothic (sometimes called Green) Line. The men of the 3rd Battalion moved quickly and pressed the retreating Germans. We surprised them with our ability to move fast and maneuver our vehicles over impossible terrain. The Germans continued to demolish the road before us.

After just over five weeks of combat, Combat Team 370 had suffered 263 casualties: 19 dead, 225 wounded, and 19 missing. There were also a number of noncombat casualties, including the sick and those who were otherwise injured.

At the north end of Pietrasanta, near a town called Querceta, there was a factory housing huge slabs of Carrara marble that had been quarried from the mountains above. As I headed to the battalion outpost just north of Querceta, the Germans began shelling. I ducked into the factory as the shelling continued. When the slabs of marble began getting hit, the shards of stone struck like shrapnel and the shelling became even more dangerous. I got out of there in a hurry.

In Pietrasanta we relieved a British unit during a period of heavy shelling by the Germans. It was afternoon, and despite the bombardment, the British paused for tea. I was invited to join them as the area around us seemed to explode, yet none of us was hurt or even excited during that curious and surreal respite.

Mount Cauala dominated Seravezza, and every move that our troops made in the shattered town was visible to the enemy in the hills above. Medium and heavy artillery raked the buildings at regular intervals, and small-arms fire swept the streets if men appeared. Careful reconnaissance was made for observation posts and approaches to the river crossing, and company commanders were given the plan of attack. Company I would attack Mount Cauala on the right, Company L in the center, and Company K on the left. K Company would lead out, carrying the telephone wire for communication.

With the coming of daybreak, the Germans had begun to counterattack on the mountain. Bill Rich, a corporal I knew in K Company, told me when he came off the hill later that morning, the Germans had kept coming despite our heavy fire. He thought they were fanatics.

German mortar fire and grenades could not dislodge our men, and they stuck to their position throughout the afternoon despite dwindling ammunition supplies. Pvt. Jake McInnis of Company K was one of the mainstays in this defense, personally killing over a dozen Germans with his Browning automatic rifle before being knocked out by a concussion grenade. He was taken to the rear but returned days later. His stand that day earned him the Silver Star.

I had volunteered for the ammunition supply detail with about a dozen men. I carried a metal box of ammunition in each hand. The boxes were rectangular and weighed about 25 pounds each. I loosened the sling on my M-1 rifle and slung it over my back. The first time I saw the Germans up close and shooting at us was at Seravezza. As we approached the hill, we looked up and could see a German machine gun raking our position. There were two German soldiers manning the gun, and our fire hit one. The other carried him away, and we continued toward our goal. When we reached the base of the hill, the Germans unleashed a tremendous artillery barrage. We crouched for a time and then continued on our way. Halfway up the hill we encountered more machine-gun fire and mortars. Shrapnel was flying all around, and some of it, quite hot, landed on my clothes, burning through to the skin. Some in our detail were hit. The detail could not continue and returned to the base of the hill. We had failed in our mission to supply ammunition, and soon other men from the rifle companies were coming off the hill. It became a mess. I will never forget the smell of burning gunpowder as the shells exploded all around us. I lost my appetite for several weeks after this experience. For a while I thought I had been gassed; however, it was the burning cordite that came from the exploding shells that had made me ill.

During the battle for Seravezza a large number of the battalion’s officers and enlisted men were killed, wounded, or listed as missing in action. Most of those listed as missing were later confirmed as killed in action. Lt. Lionel Ladmirault of Company I, an African-American from Louisiana with blue eyes, blond hair, and white skin; Lt. Ralph Skinner of Company L; and Pfc. Hugh Portee were killed in action. Lt. Skinner, although mortally wounded, continued to lead his men against a German counterattack until he died. He was awarded the Silver Star posthumously. Pfc. Portee was near me during our effort to supply ammunition at Seravezza. I knew he had been hit in a period of heavy fire, but I was unaware until later that he had died. The battalion suffered 70 casualties in just one day, and there were scores of men suffering from battle shock and fatigue. I was probably in shock but did not know it.

Official Recognition

On Oct. 17, the regimental commanding officer reported that Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond would inspect the battalion at 1300 hours. Maj. Gen. Almond (1892-1979), who was the commanding officer of the 92nd Infantry Division, believed in segregation and opposed integration of the armed forces.

Maj. Gen. Almond appeared promptly and marched up and down our formations. Col. Clarence W. Daugette and each company commander went with him. The general stopped in front of me and asked how long I had been with the battalion. He talked to my commanding officer, Capt. Hugh D. Shires, and with Col. Daugette and ordered them to award me the Combat Infantryman’s Badge “for exemplary conduct in action.” I guess the award was for trying to get ammunition onto the hill above Seravezza and for surviving almost two months of continuous combat. At any rate, I did receive the much-sought-after badge and $10 more in pay each month. After the war, all who had received the Combat Infantryman’s Badge were entitled to a Bronze Star upon request. I received my Bronze Star medal years later from the War Department.

On Nov. 4, 1944, Combat Team 370 was dissolved and returned to the 92nd Infantry Division. Col. R.G. Sherman, commanding officer of the combat team, issued the following General Order:

As this Combat Team passes into history, I, who have had the privilege of commanding it, desire to review, with you, some of the highlights of its brief, but extremely active life. Consisting of selected officers and men, this Combat Team was designated for immediate combat duty in an active theater and sailed from the United States, 15 July 1944, for the Italian Theater. In addition to its Combat Mission, Combat Team 370 was charged with the duty of preparing the way for the remainder of the 92nd Infantry Division, soon to follow in our footsteps.

Three weeks after landing in Italy, Combat Team 370, then a member of the famous 5th Army, found itself fighting at the front as a team-mate of the old and experienced 1st Armored Division. Never have two units worked more in harmony or with better results—across the Arno River—over Mount Pisano—into the Gothic Line defenses near Bagni di Lucca—armor, infantry and artillery, each assisting the other, while their respective supply units, also working together, kept the assault echelons well cared for in food, ammunition and other essentials to combat.

The record made by Combat Team 370 is enviable and is one to which we, as the first colored Combat Team in the European Theater, can well point with pride.

Men who were killed in action and could be identified became the responsibility of the regiment’s graves registration officer. His responsibility was to arrange for temporary burial. There would be every effort to identify the body and to send it back to temporary burial sites well behind the lines. Later those men who had died in action were gathered, and their burial place became the U.S. Military Cemetery in Florence.

Today, that cemetery honors 4,402 soldiers, sailors, and airmen. I have been there three times, most recently in 2013. Few places I know of are more beautiful than Tuscany, and in a tiny corner of that stunning region of Italy lie 400 African-Americans, descendants of slaves, who marched, fought, and died fighting and defeating the great evil of Nazi Germany. The blood of Buffalo Soldiers mingles in historic soil with the blood of the ancient Romans.

The names of another 1,409 men fill a Wall of the Missing. One of them was the last African-American infantry officer killed during our tenure in combat. Why his body is listed as missing in action I don’t know. That was Lt. John M. Madison from Company I, winner of the Silver Star, Bronze Star, and Purple Heart. He is listed on the wall as missing in action, yet he appears in our battalion journal as wounded then killed on April 5, 1945.

My last visit to the Florence cemetery occurred in the process of making a documentary film about my book and the remarkable gratitude the Italian people of Tuscany have shown toward the Buffalo Soldiers (see left).

Unheralded Heroism

The early days of December were clear and cold. The 3rd Battalion was ordered almost 30 miles east and attached to the 6th South African Armored Division’s 11th Armored Brigade at Castel di Casio. This sector was deep in the Apennines, northwest of Florence and north of Pistoia along Highway 64.

The South Africans had fought with the British 8th Army and defeated Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps in the North African desert in 1943. We remained alongside the South Africans through December and January. At first we were housed in a castle, but we later moved to a small factory and then to a farmhouse in the mountains.

The 3rd Battalion was now operating alongside Brazilians and South Africans as part of an international force.

On Dec. 23, we saw the first heavy snow cover the North Apennines, and the air was cold and windy. Some of our troops were issued white snow uniforms. It seemed unreal to me that African-American troops from the American South were wearing snow-white uniforms and fighting in 10-foot-deep snowdrifts.

From our position 30 miles to the east, along Highway 64 leading to Bologna, we learned that the Germans had attacked our division before dawn on Dec. 26 at several points on a six-mile front along the Serchio River.

During a German attack that day, 26-year-old Lt. John R. Fox, an artillery observer with the 366th Infantry’s Cannon Company, was killed after calling down artillery fire on his observation post, the second floor of a house in Sommocolonia. The 366th Infantry was the regiment commanded by African-American officers that Maj. Gen. Almond did not want to accept into the 92nd Division. Fox was recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross at the time, but his widow did not receive it until May 15, 1982—38 years later! The posthumous citation noted that his body was found among those of “approximately 100 German soldiers.” Another 15 years passed before President Bill Clinton awarded him the Medal of Honor.

There were many other instances of heroism. On April 7, we established battalion headquarters at Querceta; the 3rd Battalion was put in regimental reserve. We heard that Lt. Vernon Baker, Company C, 370th Infantry, in leading his weapons platoon on April 5 and 6, had encountered the enemy near Massa and, in a series of heroic actions, had killed nine German soldiers; destroyed three enemy machine-gun positions, an observation post, and a dugout; then covered the evacuation of several of his wounded comrades. Later we learned that Lt. Baker had actually fought his way into Massa and radioed headquarters that he was there. He was not believed and had to fight his way back to our lines. For his action that day, Baker received the Distinguished Service Cross. Fifty-two years later, he was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Bill Clinton.

Early on the morning of April 9, I moved with other battalion headquarters personnel by truck across the Cinquale Canal. We crossed on a Bailey bridge built by our engineers and moved into a very large villa. As we approached the villa, we saw fresh vehicle tracks, and inside we found food still on the table. Apparently the Germans had left only minutes before. As I was standing in the doorway, facing inward, a loud explosion blew me 10 feet inside. Explosions continued all around. I was on the floor and felt my entire back stinging. I slowly examined myself. All my arms and legs were still in place, but I discovered that a small piece of shrapnel had entered my right shoulder. The battalion medical staff was close by, so I took myself to the medical officer, Capt. Young. He took off my combat jacket, shirt, and undershirt, gave me a shot of tetanus, and poured sulfa powder over the wound after removing the shrapnel. Then he wrapped me up and told me to get dressed. I looked around the large medical aid station and saw wounded men lying all over the floor. They had been brought to the aid station and just left there. The more seriously wounded were later evacuated while others like me were sent back to their units. That day I looked out from the aid station and was amazed to see the Ligurian Sea. We had fought very close to the sea for many months, but I did not know it was right there. Viareggio is on the Ligurian Sea, and I went through the city several times without noticing the water. As a result of the shrapnel wound, I was awarded the Purple Heart.

Fighting Fascism and Jim Crow

At 1920 hours on May 2, the battalion received word that the war in Italy was over. The battalion journal notes, “Finito la Guerra in Italy.” The night the war ended, there was much celebration in battalion headquarters and even more out in the streets of Pontremoli. Partisans and others were firing guns, and crowds were drinking wine. The whole scene was wild. The Italian citizens of Pontremoli called for our commanding officer, Col. Daugette, to come out onto the balcony of our headquarters and greet the civilians. The colonel was somewhat reluctant to do that because the Italians were really wild at the end of the war and were shooting everywhere in their jubilation. In fact, some of them shot against walls, and the bullets ricocheted and hit the person who had fired. However, Col. Daugette did eventually step out onto the balcony, where he was cheered passionately by the Italians. Just a few days later, on May 7, at 1630 hours, I noted in the battalion journal, “The war in Europe is over!”

During the war, the performance of the 92nd Infantry Division had been criticized by senior officers. That criticism was answered by Lt. Col. Marcus H. Ray, who commanded the 600th Field Artillery Battalion. Ray, an African-American, in speaking of young African-American officers said, “Therefore, I feel that those who performed in a superior manner and those who died in the proper performance of their assigned duties are our men of the decade and all honor should be paid them. They were Americans before all else. Racially, we have been the victims of an unfortunate chain of circumstances backgrounded by the unchanged American attitude as regards the proper ‘place’ of the Negro [sic]. . . .”

I believe Col. Ray’s comments are an excellent summary of what happened to the 92nd Division. However, the colonel wrote as an artillery officer, and I write as a (then) corporal in the infantry who was present when the actions that resulted in much of the criticism occurred. Ray lays much of the blame on the “unchanged American attitude” concerning the proper place of African-Americans.

His comment is correct but polite. I agree with those African-American leaders at the time who said it was Jim Crow and not a lack of education or adequate training that affected our division’s performance. We were fighting the Nazis and Italian Fascists with one hand and Jim Crow with the other. Many of us from the North, East, and West had never before encountered the kind of racial discrimination and segregation we faced in the army. Soldiers from the South knew what segregation and discrimination were really about, and many of those rural young men with low test scores who formed our ranks felt they were often being sent on suicide missions. We were hobbled by stragglers, yes, but we fought on and in the last weeks of the war achieved a remarkable victory with our 65-mile march through the Apennines from Barga to Pontremoli. We defeated the Nazis and Italian Fascists, causing thousands of them to surrender, but we did not conquer Jim Crow.

In 1978, Philippa, my wife, and I visited Italy for the first time since the end of the war. We rented a car in Paris and drove to Italy. Naturally we stayed in Viareggio, since that had been the headquarters of the 92nd Division.

Walking in the little shops that dot the beachside, we came to an artist’s studio. Philippa, an artist herself, said, “Let’s go in.” The artist was there; and as we looked around, I said to him in Italian, “I was here in 1944 and 1945.” He was a big, gruff-looking Italian, and he said, “Tu Buffalo.” I said, “Si.” He started hugging and kissing me with the great emotion common to Italians. He opened his wallet and pulled out an old card that identified him as a partisan. His name was Bruno Tintori, and he described how he had helped us carry ammunition over the mountains. He took us next door to a bar, introduced us to his friends, and we talked and drank grappa the rest of the afternoon.

Bruno Tintori is now dead, but I later learned that he had become one of Italy’s most famous contemporary artists. Bruno Tintori’s expression of gratitude for what the Buffalo Soldiers had done for Italy, fighting in the rugged North Apennine mountains and freeing them from the yoke of Fascism and Nazism, will always be remembered. To the Italians we were first class. To the Italians we were heroes.

IVAN J. HOUSTON, a member of the Academy, retired in 1990 as the chairman of Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Co., in Los Angeles. He is the author of Black Warriors: The Buffalo Soldiers of World War II.

After graduating from college, you went to work at Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Co., which was founded in the 1920s to assist African-Americans who were unable to purchase life insurance. Describe some of the changes that you witnessed over the course of a long career in insurance.

The changes that I have witnessed since joining the company in 1948 have been truly amazing. Nearly all of our policyholders were African-Americans, working-class individuals who were serviced by agents going door to door in segregated communities

Yet until the late 1960s, African-Americans were employed by life insurers mostly for marginal jobs—janitor, messenger, etc. (New York and some of the New England states with Fair Employment Practices Commissions may have been the exception.) At Golden State, all of our employees were African-American, and most had a college education. Our operation was well run and highly efficient.

In 1948, when I started my career, the only major insurance association that admitted black companies was the Life Office Management Association, which was then headquartered in New York. It wasn’t until the late 1950s and into the 1960s that African-American insurers were admitted to the other major life insurance trade associations.

During the 1950s, there were about 60 black life insurance companies of various sizes. Most were in the South. These companies had formed the National Negro Insurance Association (NNIA) in 1922 (the name was later changed to the National Insurance Association). The NNIA met annually at the home office of one of its larger member companies, and until about 1960, the hosting company would have to struggle to find housing for meeting delegates because hotels refused to accept African-American customers. (The National Insurance Association no longer exists, and most of the companies that were a part of that organization have been merged into larger companies in the industry.)

With the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, major life insurance companies began to hire black employees and agents. While this was good for them, our company began to lose outstanding recruits and other employees. It was difficult to maintain competitive wages and benefits. To maintain a quality workforce, we even undertook reverse integration.

You qualified as an actuary at a time when the profession wasn’t particularly diverse. What changes have you seen in the actuarial profession over the course of your career?

When I first got involved in professional actuarial organizations, I saw few women and hardly any African-Americans. That has changed, especially for women, but I still don’t see a significant number of African-Americans.

The International Association of Black Actuaries, of which I am a member, is making a real effort to recruit African-Americans to the profession. I received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Association of Black Actuaries in 2008 because I was among the earliest black actuaries in this country. They flew me to their convention in Washington to receive the award. The room was full of African-American actuaries and actuarial students. It gave me a wonderful feeling just to see their numbers and to know that these professionals and young students are pursuing what I think is a great career.

How did your experiences fighting in Italy help you as

you moved forward in a long and successful career as

an -African-American businessman?

Fighting as an African-American soldier in the infantry in Italy was an experience that is forever engraved in my mind. I have said to my family and friends that nothing worse could ever happen to me. Yet, for some crazy reason, I learned much about people, about suffering, about being happy, and about being proud of accomplishments in the face of tremendous odds. You learn there is always a way of attaining your goal.

You’ve been active in numerous civic and religious organizations, particularly in Los Angeles. To what do you attribute your lifelong involvement in public service?

There are many reasons for becoming involved in civic and religious organizations. First you must like the organization and its mission. You must also determine what you have to offer and what you can gain from being involved.

I was active in life insurance industry organizations, even serving as chairman of the Life Office Management Association (LOMA), because they were a great professional resource for me and my employees. At one time I was president of the Los Angeles Actuarial Club because I felt I had something to offer as a company actuary. I volunteered with the Los Angeles Urban League because it was devoted to preparing African-Americans for jobs. I was involved in the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce and the California Chamber of Commerce because they were engaged in the politics of the city and the state in which I worked, and political decisions always have an effect on business.

Since my retirement, I’ve become a member of the board of trustees of Catholic Charities of Los Angeles. Since I no longer have a company to be concerned about, I can now focus on those who are in much need—the poor and the homeless.

In his book, Black Warriors: The Buffalo Soldiers of World War II, Ivan Houston describes his battalion’s Sept. 4, 1944 capture and liberation of the 15th-century Villa Orsini. The current owner of the villa, Mattea Piazzesi, came across Houston’s book when she was updating the website for the bed and breakfast that she runs there. Piazzesi contacted Houston about using excerpts from his book and invited him to visit the villa, now named the Villa LaDogana. Houston took her up on the offer and, accompanied by his family, returned to Lucca in September 2012. He was honored in nine towns and villages that his division had liberated in World War II.

“I was astounded at the reception and gratitude given to me by the Italians in many villages and towns in Tuscany,” Houston said. “They kept saying that the Buffalo Soldiers—African-American infantry troops—gave them their freedom!”

During that trip, Houston discovered that the city of Lucca commemorates its World War II liberation by Buffalo Soldiers every year in September. In 2013, Houston returned to lead the celebratory procession.

Accompanying him on that trip was a filmmaker, who shot footage for a documentary about the Buffalo Soldiers of World War II. A 12-minute trailer for the documentary, which is expected to be completed in 2014, can be viewed at www.pacificfilmfoundation.org.

“The armed forces in which I served relegated most African-Americans to service units in support of the combat forces but never really wanted to place them in direct combat. We of the 92nd Infantry Division were one of the few exceptions. We fought the Nazis and the Fascists with honor, face-to-face in the rugged mountains of Italy. We suffered hundreds of casualties and in the end defeated the Nazi proponents of a master race and their allies. Yet the heart of America did not change toward its African-American soldiers or its African-American citizens. When we returned, we encountered the same segregation and discrimination that had existed since the end of the Civil War. Nothing had changed.”

—Ivan Houston—Black Warriors