By Michael G. Malloy

Dog is said to be man’s best friend, and cats are notoriously curious … so what are we doing to make sure these curious, furry friends stay healthy throughout their lives?

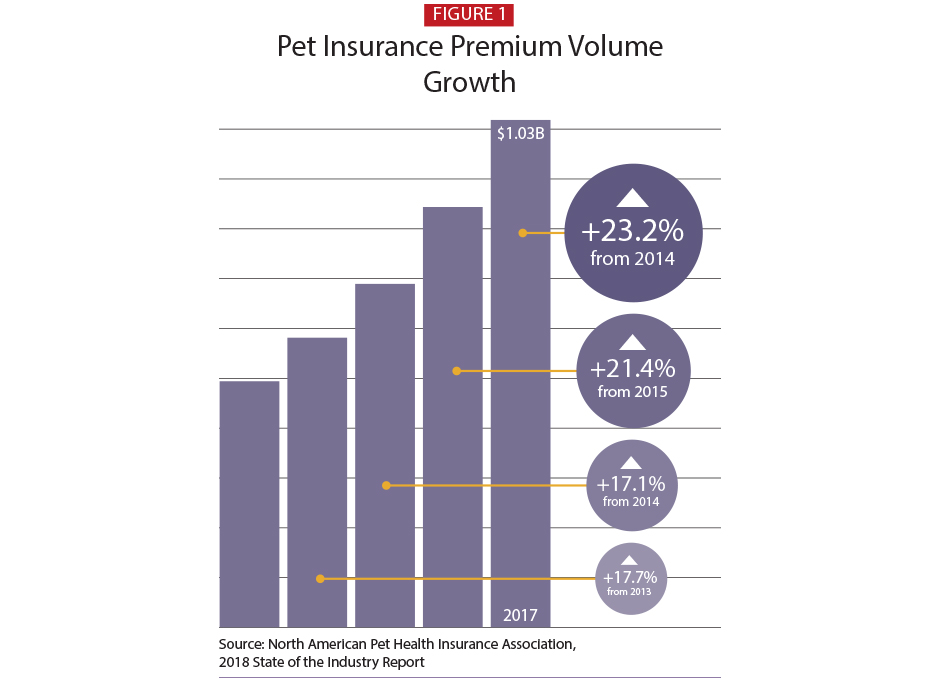

Insurance for pets, while a relatively small sector of the insurance industry, is showing signs of growth as pets become more integrated into people’s lives in a dog- and cat-crazed culture. Only 1 to 2 percent of pets in the United States are covered by insurance, according to the North American Pet Health Insurance Association (NAPHIA), but the growth has been steady in the past five years. NAPHIA’s 2018 state of the industry report, released earlier this year with data compiled by Willis Towers Watson, showed that about 2.07 million pet owners in North America carried insurance for their dogs and cats at the end of 2017, with most of those in the United States. That was up 16.8 percent from 2016, with U.S. premiums totaling $1.03 billion—double the $500 million comparable figures from 2013. Premium volumes were C$161.1 million in Canada last year, up from C$91 million five years ago.

“People see pet health insurance as a way to be able to afford some of the more expensive treatments for their animals,” said Lori Weyuker, lead actuary with Nationwide Pet Insurance.

“Pet insurance is becoming a hot topic—and right now, anything having to do with pets in the United States is a hot topic.”

NAPHIA Executive Director Kristen Lynch said pet insurance is and has been more established in other countries—notably in the United Kingdom and other European countries like Sweden, where the coverage level tops 30 percent—in part because it has been around much longer. While NAPHIA does not project industry growth, Lynch said pets being considered “part of the family” is a key factor in its increase, especially with people posting photos of their pets on social media, including the ubiquitous “cat videos” on Facebook and Twitter, and calling themselves “pet parents.”

“It’s about how much people value their pets, and how easy do they want to make it to not think twice about taking their pet into the vet,” she said. “As the human-animal bond grows, and it’s part of the culture and more accepted in society that pets are part of your family, you’ll see the expression in the animal-health world that pets have moved ‘from the barnyard, to the backyard, to the bedroom’—and that’s been in one generation. In places like the U.K., it’s been over many generations. Also, as we increasingly urbanize, our pets live closer to us and become more important. People walk to a café and sit with their dog, book day care for their dogs, and they become literally like extensions of our children,” which can be true for either empty-nesters or for people who may not have children, she said.

Lynch said when she first got involved in pet insurance about 10 years ago she was surprised it was becoming a viable product, but she soon saw that it had been around much longer in other countries. In many nations, insurance is not just regulated, it’s legislated—so in Europe, where pet insurance is more entrenched, liability coverage for pets is often required, which can lead to opportunities to offer pet insurance.

More employers are offering pet insurance too, Lynch said. NAPHIA found in a 2017 study that more than 6,500 companies in the United States and Canada—all but about 250 of those were in the United States—covered about 80,000 employees’ pets under such policies. It’s a “quirky market,” she said. “It requires so many different parts of the brain to understand how people relate to their pets. It’s not like your car—when someone’s buying pet insurance, it’s an emotional relationship. When someone’s making a claim, that’s an emotional relationship. And when they’re upset with you or when they’re happy with you, it’s an emotional conversation.”

Health vs. P/C Elements

From a regulatory perspective, pet insurance falls under the property/casualty area of insurance, because pets are, in effect, property. “It functions more like human health, but it’s underwritten like property and casualty,” Lynch said.

Pet health insurance falls under the regulatory category of property insurance, but “other aspects more closely resemble health insurance, because that’s really what it is,” Nationwide’s Weyuker said. “If you’re a pet insurance company and you’re trying to figure out what kind of actuary to hire, the best answer is to hire some of each. From a product design perspective, it is really health insurance—it’s not car insurance for dogs. So when you’re an actuary in a traditional pricing role in pet health insurance, your job really is pretty similar to what a human health insurance actuary does.”

Weyuker, who has a health actuarial background and previously worked for Kaiser Permanente, Anthem, and other health organizations, said Nationwide had a long relationship with Veterinary Pet Insurance (VPI), which began in 1982 as the first U.S. pet insurance company. It rebranded VPI to Nationwide pet insurance about four years ago, when Weyuker joined the company (see sidebar).

A notable difference for pet versus human health insurance is that pre-existing conditions for animals generally are not covered. This is to avoid a situation in which a pet owner could find out his dog or cat has cancer or another disease or condition requiring expensive treatment, and then tries to buy insurance to cover it.

“Insurance companies in the pet insurance business need to ensure that ongoing risk is sustainable,” Weyuker said. Pet insurance, being a purely optional purchase, “would encounter vast anti-selection unless there is a protocol to deal with pre-existing conditions in pets” if that were the case, she said. And the still-nascent pet health insurance industry is relatively unregulated—compared with human health insurance, which has pre-existing condition coverage generally mandated under the Affordable Care Act.

Plans offered by many insurance companies cover accident and illness, although some carriers have wellness plans that include things such as routine dental cleanings. And while most insurers only cover dogs and cats, Nationwide covers a range of exotic domesticated animals—birds, rabbits, snakes and other reptiles, pot-bellied pigs—although fish are excluded, Weyuker said.

Other more nontraditional treatments are available and could be covered by insurance too, including behavioral treatment—like humans, animals can develop anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder from being traumatized by a bad owner or attacked by another dog, for example. Weyuker noticed a number of alternative treatments at a veterinary conference earlier this year, including acupuncture, therapeutic massage—and even THC, the active ingredient in medical marijuana, which can be used to treat pain in some pets.

Policies have no face-value death benefit akin to life insurance, although they can cover euthanasia. Life insurance for a pet would very rarely make sense, with a notable exception: Nationwide’s predecessor company’s first policyholder was Lassie, the famous collie(s) who starred on TV and movies. “But unless you’re like Lassie, life insurance doesn’t make sense,” Weyuker said.

For an actuary designing pet health insurance plans, companies that want to sell their plans need to file with state insurance department P/C sections, and after signing an actuarial memo and giving the information to the department, the actuary communicates with it until the plan and rates are approved for sale in the state, she said.

Actuarial Enterprise

Laura Bennett, the first actuary in North America to work full-time on pet insurance, said that when she began in the early 2000s there were few if any actuaries in the field. “There was some work done but there was really no actuarial science applied to pet insurance work,” she said.

Noting the mesh of P/C and health, Bennett saw it as a good opportunity. Pet insurance companies were often “managing general agencies” that partnered with P/C insurance companies. And even though pet insurance did not fit naturally as a P/C concern and was “sort of squeezed between both worlds, it was a very interesting hybrid” that she enjoyed working on.

Bennett’s idea came out of a business-plan competition at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton business school, where she was working toward an MBA. After a friend got socked with $5,000 in expenses thanks to a sick cat, sparking the idea, Bennett and her three team partners won the 2003 competition. In developing their plan, they went to about eight veterinary practices, asking for client information. In exchange, the vets gave them consulting reports on the types of pet owners they had in their practices and where potential opportunities were.

When an actuary takes on a new line, an insurance company might see what others are doing and copy it, which can be typical in P/C practice, Bennett said. Originally from the United Kingdom and never having been a broker, “All of it was brand-new to me, so I said, ‘How am I going to get data?’” she said. They also asked for, and received, data from the University of Pennsylvania’s veterinary hospital, one of the largest in the country, and created a database. She and one of her team partners founded Embrace Pet Insurance, while the two others created Petplan Pet Insurance—those remain two of the major pet insurance players today.

“We basically combined the data to create a database of procedures and claims and built the pricing from the ground up,” Bennett said, throwing in a “smell test” about what else was on the market to make cost adjustments. “You have to scrub the data very carefully,” including such things as why people don’t bring cats to the vet as often as dogs. Bennett’s work evolved into developing customizable policies in which people got to pick and choose what kind of coverage they wanted and if they wanted wellness coverage.

Both Weyuker and Bennett said that being a pet health insurance actuary requires building a database of information. Unlike publicly available human mortality/morbidity tables—such as those easily accessible on the Social Security Administration’s website, for example—“there’s no such thing for pets, because that information is not publicly available,” Weyuker said. “If you’re an actuary working in this business, you have to create your own tables; everything that you do in your job, you have to create yourself. It’s very uncharted territory. If you’re a good actuary, you look at all the data you have and analyze which of these variables are correlated with risk.”

Bennett notes how far the niche industry has come in just a few years. “If you look now, 15 years later, the products have all gone upscale—many are full-coverage, with more ability to pick and choose” than what was available previously, she said. Typical coverages today can include exotic treatments such as acupuncture, chemotherapy, hydrotherapy, hyperbaric chamber treatments, oxygen treatments—“pretty much anything veterinarians prescribe as a medically necessary treatment, you can get covered,” she said.

“We created something from nothing as a general design, and once we started selling, we started to get some actual experience,” she said.

“The good news with pet insurance is it’s a large number of small policies with a large number of small claims. You can quickly gauge if your pricing is reasonable or not—certainly in the first two years, it will be very clear.”

Bennett described it as a “factor-driven” risk-based model, with things such as an animal’s age, sex, breed, location, and other components, along with deductibles and annual maximums. “It’s been a fascinating process because it wasn’t just the risk profile of the dog or the cat, but also the owner—the pet parent. We had to make some assumptions” about behavior, she said. For example, people behave differently with pet insurance than without it, getting tests or surgeries that they might not have otherwise.

Pet insurance has a high “moral hazard,” Bennett said, by which a party, in this case the owner, has control over treatments, which translates to costs. So determining owner behavior is also a key. And many plans are offered online, with owners able to pick and choose from a variety of coverage categories they want.

“That’s more subtle,” Bennett said. “How do you determine what kind of person it is? Are they going to claim a lot? Are they a first-time pet parent who doesn’t know dog costs? We found the customizable approach made the person tell us exactly what kind of person they were. Or, they might suspect their dog has something and want to get insurance with the hope they can get it paid for. You can’t build in every single thing, but the choices you make in your coverage tend to reflect what you want.”

And not surprisingly, different breeds have different risk levels, Bennett said. A larger dog like a Labrador, for example, has more risk than a smaller dog like a Jack Russell terrier, and premiums reflect that. “The breeds tend to be grouped,” she said, adding there might be eight groups among the 250 different dog breeds, depending on the company.

Growth Projections

John Volk, an analyst with Brakke Consulting in Chicago, a management consulting firm that specializes in the animal health market, noted the double-digit pace of growth of the industry in the past few years and that there is growing amount of private-equity investment in animal-health and veterinary practices.

Volk, who has worked in the animal-health field for about 20 years and has worked with NAPHIA, said there are about a dozen main companies in the pet insurance field. And while there is no universal pet census, he estimated that only about 2 percent of dogs that are regularly taken to veterinarian offices have pet insurance. (A partnership of four organizations announced in July it was undertaking a three-year “cat census” of Washington, D.C.’s feline population—www.dccatcount.org—that will cost $1.5 million.)

Noting NAPHIA’s report, he said that “even though it’s a small industry, it’s growing at a double-digit pace, and it seems like it’s [been] increasing over the past few years, so more and more pet owners are finding it valuable to them.”

But many people aren’t motivated to get pet insurance until they feel they need it. While pet health care can cover high-dollar treatments like cancer or surgery, “a lot of people roll the dice,” he said. Like Lynch, he noted that people increasingly see pets as members of their family. “I think we’re going to continue to see pet insurance grow. Over the next five to 10 years, it could get into the 7, 8, or 9 percent range” of pet owners, he said.

Veterinarians see a primary benefit of health insurance as compliance with responsible pet care, as those owners who have insurance are more likely to treat an injured pet and use their services—as opposed to euthanizing a pet—than those who don’t. “By far the most common pet health insurance in the U.S. is accident and illness insurance that typically insure against unforeseen health episodes—either illness, disease, or injury—and from that standpoint the primary function is to make sure there’s money there to treat a sick or injured animal,” Volk said.

One question a typical pet owner might ask is will having pet insurance save them money. NAPHIA’s Lynch said that many people will look at it from a return-on-investment point of view—will it even out over the years? “But you don’t expect a return on investment from an emotional product. We know at some point in our lifetime, our pets are going to get sick. They’re going to have some major incident, or a couple of them. For me, it’s about having confidence—I don’t worry, and when my pet is sick, I take them in. If you stay covered, you’ll get that back; if you don’t, you don’t.”

“The whole question of saving money intrigues me from an insurance standpoint,” Volk said. “When I insure my car—or my life—I’m hoping I won’t have a claim. So I find it a little ironic that people will talk about getting their money back. The concept is, over time, how likely is it over time that your pet is going to have some episode that will be several hundred—perhaps several thousand—dollars, and that’s not uncommon for pets. The basic idea is to have that money there for non-routine expenses.”

One such pet owner is Courtney Estep, of Alexandria, Va., who had a purebred dachshund named Brody who died in January this year at the age of 10. With their familiar hot-dog-shaped bodies, dachshunds are often susceptible to spinal issues, including one called intervertebral disk disease (IVDD). Estep said she got a plan from Embrace Pet Insurance to cover Brody, with the foreknowledge that he might be susceptible to IVDD. Four operations of $8,000 to $10,000 apiece later, she was glad she had it.

Her plan’s monthly premiums rose from $30 to $50 to more than $100 over time but covered 90 percent of costs of up to $10,000 a year, with a $200 deductible. “To say I got my money’s worth out of the policy would be an understatement,” Estep said. “For the first five years, I thought they’re just raising the rates,” she said—prices typically rise as a dog or cat gets older. But when Brody had his first IVDD incident at about age 5, “it was well worth it,” she said. “It was the comfort of going to the vet. Brody typically had an annual visit—even if was for eating something he shouldn’t or getting hurt chasing a squirrel—and and I never had to worry about if I would treat him because of cost.”

Owner Attitudes

A 2015 study by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) in conjunction with Mississippi State University’s Department of Agricultural Economics found that such things as insurance premiums, reimbursement levels, unlimited benefits, and wellness plans all have significant effects on pet owners’ purchase decisions.

“We found that if there was a wellness plan included, consumers were more likely to visit the veterinarian more frequently than those without a wellness plan,” said Bridgette Bain, an economist and AVMA’s associate director of analytics.

The study found that, after certain price points, those who spend more on their pets, spend more on vet visits, regardless of whether they have insurance, Bain said. The survey of 526 people showed that 75 percent viewed pets as a member of their family as opposed to property, and that almost 60 percent allowed their pets to sleep in their bedroom, either on their bed or the floor. It also found that the average spent on a pet in 2014, including food and vet bills, was $676.60, while the average spent on medical treatment was $248.

Risk factors also played in to people’s perceptions, though the study reported a majority—a little over half—reported themselves as being risk-neutral (see tables), and Bain said that according to the study, younger people were more likely to have pet insurance than the older generation.

“If people feel their pet is more likely to become ill, or the price of veterinary treatment is increasing, they’re more likely to buy pet insurance. But it’s not a black-and-white picture where folks who have pet insurance spend more,” she said. “It’s dependent on the type of insurance and the relationship between the owner and their pet. The more the owner views their pet as part of the family, the more likely they are to spend more. If they view their pet as property, they’re less likely to spend more.”

Surgical Corrections

Pets sometimes require surgery akin to cosmetic surgery for humans—called corrective surgery in veterinary practices, said Jennifer Maniet, a staff veterinarian with Petplan Pet Insurance. Such procedures can include everything from trimming eyelids to widening an animal’s nostrils and nasal cavity so they can breathe easier, typically seen in breeds with “smooshed-in faces” like pugs and bulldogs, she said.

“Corrective surgery is primarily to relieve the pain and discomfort in the pet,” Maniet said. Entropion or ectropion surgery—to correct conditions where, respectively, a dog’s eyelids roll inward toward its cornea or outward—are among the more common conditions and can generally be covered by insurance plans if related to a medical condition. “The corrective surgery is to avoid the causes of irritation, scratches, ulcers, infections, and ultimately pain in the eye,” she said.

In line with pre-existing condition exclusions, the first item on Petplan’s pet insurance “checklist” is a waiting period, which can vary based on past or current injuries, illnesses, or conditions. “In pet insurance, a lot of companies have waiting periods,” Maniet said. “If there are pre-existing conditions in those periods—either medical illnesses or injuries—then anything related to those conditions occurring within the policy may not be covered, depending on the carrier.” Petplan’s standard waiting periods are five days for injury, 15 days for illness, and six months for knee conditions.

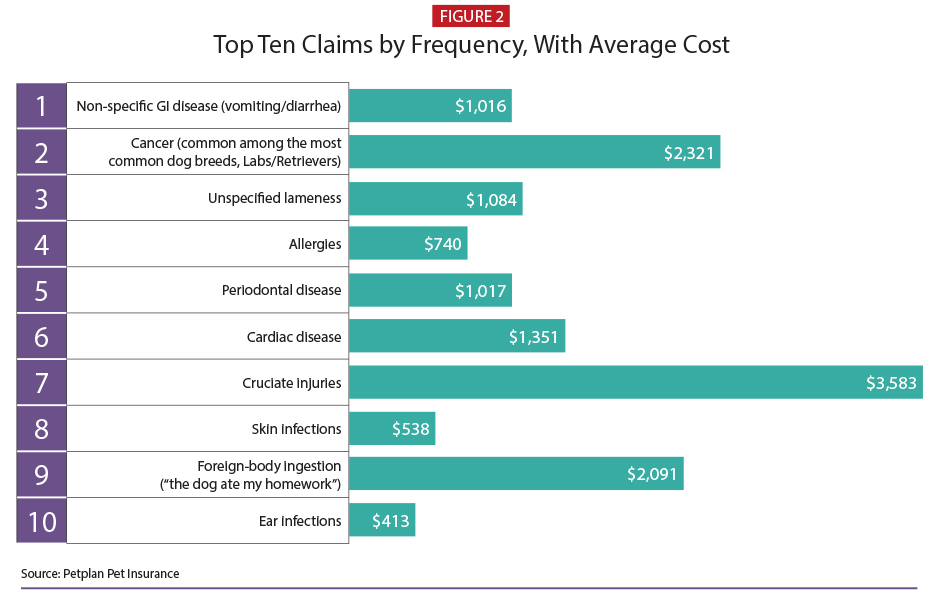

Other checklist items for potential buyers to consider include policy exclusions, what is considered standard coverage, cancer and dental illness, and if prescriptions and alternative therapies like acupuncture are covered. Common conditions and diseases for both dogs and cats also include gastrointestinal disease and cancer (see sidebar), while cruciate injuries are less common for cats. Allergies—both food and environmental—are also becoming more common in both, Maniet said.

But not every procedure is medically necessary, she noted, and thus not covered by pet insurance. Giving male dogs who have been neutered artificial testicles—known as neuticles—was a consumer fad that trended for a while but is generally not medically necessary, she said.

Vets See Growth

Veterinarian Lloyd Meisels, owner of Coral Springs Animal Hospital in South Florida, said he has seen an upward trend in ownership of pet insurance. Coral Springs, which Meisels began as a practice 40 years ago, has grown to include 24-hour emergency service with specialists in several areas, and today has 37 doctors and 120 support staff and treated about 54,000 animals last year. “What we love about pet insurance, particularly in a large emergency room, is it takes away the consternation the owner might have about how they are going to pay” for treatment, he said.

As specialty procedures emerged out of universities in the 1990s, insurance coverage was limited, he said, and many people would finance their non-insured medical needs through CareCredit, a type of credit card that can be used for non-insured medical needs, either pet or human. Today, many more alternative treatments are covered by pet insurance plans. Coral Springs has a “K-9 rehabilitation” specialist who uses sports medicine for athletic dogs and has others who practice acupuncture and Chinese medicine in addition to traditional treatments. Meisels said he first saw acupuncture used on horses when he was in veterinary school in the 1970s and thought if it works on horses, it could work on other animals, too.

“There’s no question it works on animals; it does have a scientific basis,” he said. “Treatments like that—laser treatments and other things being used by humans—are being used more, and demanded by the public.” Dogs can go from knee surgeries right into physical rehabilitation on water treadmills, “and they’re walking within two weeks,” he said. Such treatments “do work, they are beneficial, and they decrease pain and healing time.”

Patty Khuly, a veterinarian owner of Sunset Medical Clinic in Miami, a practice with four vets who treat 10 to 20 pets each per day and generates about $3 million in revenue annually, also said she’s seen an increase in the use of pet insurance.

“In my practice, it’s grown about 1,000 percent in the past 10 years. It took about a full dog’s lifetime for my pet owners to become excited about it, because that’s how long it took for their dogs to have a problem where they wished they had insurance. I planted a seed, they didn’t get it, they wish they’d gotten it—and now they’re getting it for their second pet,” Khuly said.

“Veterinarians had a healthy fear of the [pet insurance] industry at the outset that hampered its adoption tremendously in the U.S.,” in part because of concerns about a potential managed-care environment, she said.

“Now we’re seeing veterinarians more interested in the product—they see how it can help their bottom line, help them practice the kind of medicine that they want to, are not constrained by the dollar figures as much as they once were, and can recommend the best kind of treatments.”

And while only about 10 percent of her clients have pet insurance, she talks to owners when they bring in their new puppy or kitten and sees those who have insurance more frequently. “They’re getting better care that they previously had,” she said. Some plans that straddle between accident/illness and wellness plans can lead to more regular treatments, even if they have higher premiums but lower deductibles, she said.

One drawback can be that those pet owners who use insurance the most are more educated and less likely to need the peace of mind, or the “backstop of insurance to get some of the procedures done to keep their pets healthy,” Khuly said, while other clients may forego procedures like knee surgeries or other potentially expensive treatments.

“Veterinarians are on the front lines of marketing this product,” she said. “Pets are getting better care than they had previously, and when we don’t recommend it, or offer pamphlets or brochures, or discuss it during the first puppy visits, then it doesn’t happen,” she said. Pet insurance companies “have not had a major marketing presence in the United States, and that’s what’s kept them back. The fact that they’ve relied on going through veterinarians has not been the best strategy.”

Insurance companies are addressing the reimbursement process to make it more seamless for users, Khuly said, and plans can cover a wide range of items, including potentially expensive food for special diets of dogs or cats with allergies, for example. Sunset treats about 65 percent dogs versus cats, but Khuly said the insurance ratio at her practice is about 90 percent dogs. And like Meisels, she recommends and utilizes acupuncture and rehabilitation, among other specialized services.

“I always tell them you hope you lose on pet insurance. You’re only paying for peace of mind; you’re not playing to win. The house is always going to win on this one. You don’t want to have to use it. I ask them, ‘What’s the peace of mind worth to you?’”

One such pet owner is Katy Watkins, of Alexandria, Va., who got pet insurance for Felice, a rescue dog she estimates at about seven years old, after Felice developed breathing issues shortly after Watkins and her husband, Eric, adopted the Chihuahua mix about three years ago. They could not get insurance for that episode because it was a pre-existing condition, but after that traumatic event, they reassessed.

“I always thought if we had a dog that had cancer, and it was an older dog who only had a 25 percent chance of living, and we had to spend 30 grand on dog-cancer treatment, we’re not going to do that,” Watkins said. “But this was a perfectly healthy dog in the prime of life who was having a breathing crisis, and I was thinking, ‘What I am going to do?’”

She said that while bringing Felice to the veterinarian it ran through her mind that costs could run up, but told the vet “to do whatever you have to do to save my dog.” The episode turned out to be about the cost of an emergency visit—a few hundred dollars. After that, she and her husband got a premium pet insurance policy from Nationwide, with wellness coverage that costs about $100 a month, which she said covers 80 percent of meds and treatment, with a $300 annual deductible. And once Felice’s malady, which turned out to be sinusitis, cleared up, Watkins said that after a waiting period, any subsequent similar situation would not be considered a pre-existing condition and would be covered.

She was glad she had the policy when, after taking Felice to work with her, the dog ate an ibuprofen pill a coworker dropped and ended up in the hospital for two days. “There was no issue with that claim,” Watkins said. Felice’s first teeth-cleaning was considered a pre-existing condition and not covered, but since then the cleanings have been covered at 80 percent. “It’s paid for itself every year that we’ve had it,” Watkins said. “If you get your dog’s teeth cleaned and they have to do even one extraction, you’re looking at hundreds of dollars.”

Bennett, who is not at Embrace Pet Insurance any longer, said the experience was a good example of actuaries putting their skills to a new field or venture. “There are always going to be new types of insurances out there,” she said.

“It encourages actuaries to be very open-minded, because we tend to learn techniques and approaches that fit a certain circumstance. Just having new thinking about how they can approach this, even if it’s from scratch, is always a good exercise, even if it’s your own project. Actuaries are being asked to do more.”

MICHAEL G. MALLOY is the Academy’s managing editor for member content.

My Experience as a Pet Insurance Actuary |

|---|

| By Lori Weyuker

Health insurance for pets? In my years as an actuary, I had never come across this idea. With a background as a healthcare and employee benefit actuary (both rapidly evolving areas), I was no stranger to working in genres one step removed from traditional actuarial health insurance endeavors. My earlier experience included international health care consulting as well as health care predictive modeling. I had even worked with several health care start-ups prior to this, so there was some evidence that I enjoy endeavors a bit outside the box. One day while researching new insurance business ideas, an actuarial opportunity in “pet health insurance” arose. After my first reaction—I laughed!—intrigued, I pursued the idea. Three-and-a-half years later, I’ve become an quite well versed in the business, leading Nationwide Insurance Company’s Pet Actuarial Team. There are several unusual aspects to being a practicing pet health insurance actuary practicing in the United States. First, there is a blending of two distinct actuarial protocols: health/benefits and general insurance. From a pricing and product design perspective, pet health insurance is very similar to health and benefits actuarial thinking. After all, it is health insurance—but as applied to a pet, rather than to a human. From a regulatory perspective, the main influence is general insurance actuarial techniques. I’m not aware of many types of insurance that require this distinct blending of protocols. Second, pet health insurance in the U.S. is, for the most part, a new and dynamic business. With Nationwide pet insurance (formerly known as Veterinary Pet Insurance) being the first U.S. pet health insurance business commencing in the 1980s, this makes it a relatively young line of insurance. Given that, it is not overly regulated, which allows for a certain amount of creativity in product and plan design. Third, the types of claims encountered can be quite unusual. Pet health insurance claims can include items that look like what one would encounter in human health; i.e., for illnesses. For accident-related claims, however, they can range from everything from a pet stuck inside a recliner chair (and needing to be rescued), to removing a swallowed tennis ball. In another example, a dog attempting to protect its owner from an armed burglar was stabbed—surviving the ordeal but requiring sutures and a vet visit afterward. A Day in the Life of a Pet Insurance Actuary A typical day on the job might look like this: Pricing and product design. With our background as experts in ascertaining insurance risk, the responsibility of a pet insurance actuary is to design products as well as create/adjust pricing. The sources of risk to evaluate are many. In addition to the typical risks to keep in mind, we are aware of the unique aspects connected to pet health, as well as consumer behavior. Veterinarian influence. Our business is focused on the pets we insure. Regular discussions with veterinarians and other industry experts inform on the latest pet medical treatments as well as animal-specific diseases. As with human health care, alternative care is becoming more popular. Modalities for pets includes pet acupuncture, Reiki massage, aromatherapy, behavioral modification therapy, osteopathy, naturopathy, homeopathy, chiropractic—even medical marijuana, for pain. Furthermore, there are medical devices made specifically for pets. As device vendors create new equipment for pet diagnoses, veterinarians keep us up to date. In addition to medical-practice developments, pets we insure also change over time. Our block of business includes birds, reptiles, bunnies, and of course, dogs and cats. New breeds of pets continue to emerge, with their own unique health risks and corresponding treatment protocols. Consequently, it is crucial to keep current with the ever-evolving risk factors of the business. Actuarial team. As in many insurance organizations, we have an actuarial team whose members are going through the actuarial exam process. Managing each team member’s professional progression is essential to the team’s success. A unique facet to a pet insurance business’s actuarial team includes having both health insurance and property/casualty actuaries. As such, managing a team of actuaries, some of whom are training in actuarial healthcare methods, while others are within the property/casualty discipline, is unique to this business. Consideration on how to optimally blend these requires some outside-the-box thinking on the part of the team leader. We also encounter two distinct sets of actuarial vocabulary, specific to these two actuarial backgrounds. It can be a challenge ensuring that we all speak the same language with understanding. The role of a pet health insurance actuary is unique and dynamic. There’s a positive energy around helping people keep their beloved pets healthy. With this thought in mind, it is a fulfilling—and although challenging—meaningful line to be working in. |