By James Palmier and Brian Lanzrath

The data presented in this article were collected by ExamOne, a provider of paramedical and laboratory testing for life insurance companies.

Applicants’ self-disclosed Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) status as well as body mass index (BMI) are important risk factors for morbidity and mortality in both accelerated and traditional (full) underwriting processes. In combination with self-disclosed smoking and medical history (diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, high cholesterol), which was discussed in a previous issue of Contingencies,[1] these conditions constitute a majority of the leading medical inputs to the risk-assessment process.

Body weight and height were measured directly in the course of the paramedical exam and the BMI (kg/m2) was calculated. HIV and HCV status were confirmed with laboratory blood tests.All applicants were questioned explicitly on their current height and weight as well as their HIV and HCV status during a routine telephone interview preceding the paramedical exam. The nondisclosure rate was defined as the percentage of confirmed positive applicants who denied the relevant condition in the course of the tele-interview. The data does not allow us to definitively distinguish intentional nondisclosure (in which the applicant is aware of his or her condition) from unintentional nondisclosure (characterized by a sincere lack of knowledge or diagnosis). It is reasonable to assume that an applicant is less likely to be genuinely unaware of their height and weight than of a potentially asymptomatic viral infection.

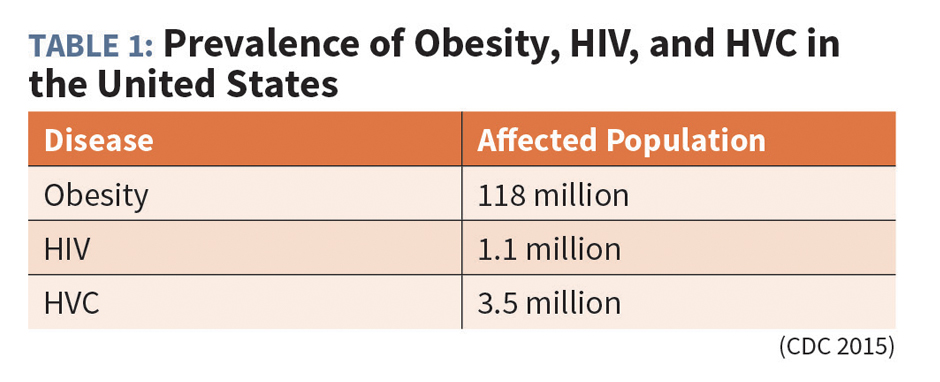

Prevalence and Risk of Obesity, HIV, and HCV in the General Population

Obesity is defined as a BMI of greater than 30. As seen in Table 1, more than one-third (36.5 percent) of all United States adults are obese. Geographically, the southern U.S. has the highest prevalence of obesity, while the western U.S. has the lowest prevalence. Obesity rates peak in middle age, with a prevalence of 32.3 percent among those between age 20 and 29 and 40.2 percent among those age 40–59, before declining modestly among adults age 60 and older.[2]

Obesity, including mild, moderate, and severe obesity, is correlated strongly with serious medical conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as excess mortality in general.[3,4] In the U.S. alone, obesity contributes to more than $147 billion in medical costs each year due to a related increase in diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic diseases.[5]

Clinically, HIV positivity is defined as the presence of an HIV infection, regardless of the stage of the disease (with stage 3 classified as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome [AIDS]). There are approximately 1.1 million individuals with HIV and AIDS in the U.S.[6] Although HIV/AIDS affects people across all age groups, geographic regions, and ethnicities, the highest prevalence is in Americans age 20–29, African Americans and Hispanics, and those residing in Florida, California, Texas, and New York.

Individuals with an HIV infection have a greater probability of future morbidity and compromised mortality. However, given treatment with current combination antiretroviral therapy, both morbidity and mortality due to HIV/AIDS have decreased substantially from the extreme levels of the 1980s and early 1990s.[7]

HCV is a blood-borne virus that infects the liver. Most new infections originate from sharing needles or other devices for intravenous drug use, although historically (prior to 1990) blood transfusions were the major source of infection. HCV infection can become a chronic, long-term condition that can severely damage the liver. Among those infected with HCV, approximately 75 to 85 percent will develop a chronic infection. Approximately 3.5 million individuals in the U.S. have chronic HCV, although many individuals with chronic HCV infection do not know they have the disease until its later stages. Consequences of chronic HCV infection include cirrhosis of the liver, cancer, and death.[8] As with HIV, however, new antiviral medicines are dramatically altering the prognosis of chronic HCV infection.

Applicant Obesity Nondisclosure

We analyzed 40,354 applicants between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2016, who completed a self-reported medical history tele-interview, which included a question regarding their height and weight, followed by a paramedical examination that confirmed the two values. Applicants were placed into one of four weight classes depending on their BMI:

- Normal BMI (< 25)

- Overweight (25.0–29.9)

- Obese (30.0–39.9)

- Morbidly Obese (40+)

For the purposes of this study, nondisclosure was defined as the proportion of applicants with a confirmed obese or morbidly obese BMI (≥30) who claimed a height and weight equating to a BMI of below 30. A total of 13,362 (33.1 percent) of study applicants met our criteria for obesity or morbid obesity, only slightly below the 36.5 percent prevalence estimated for the general U.S. population.

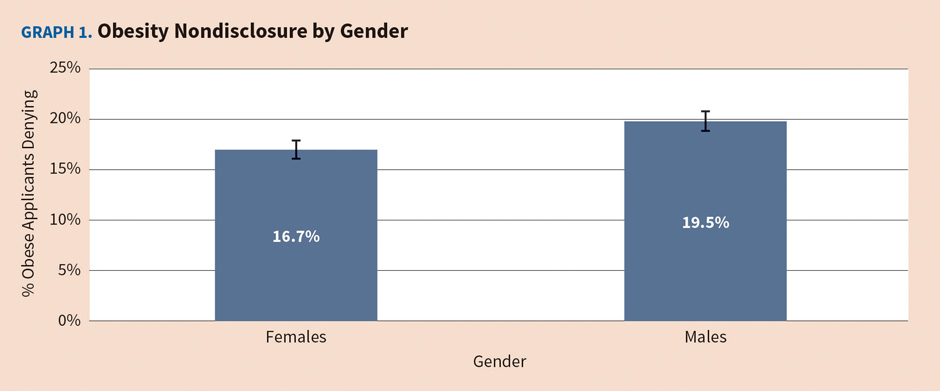

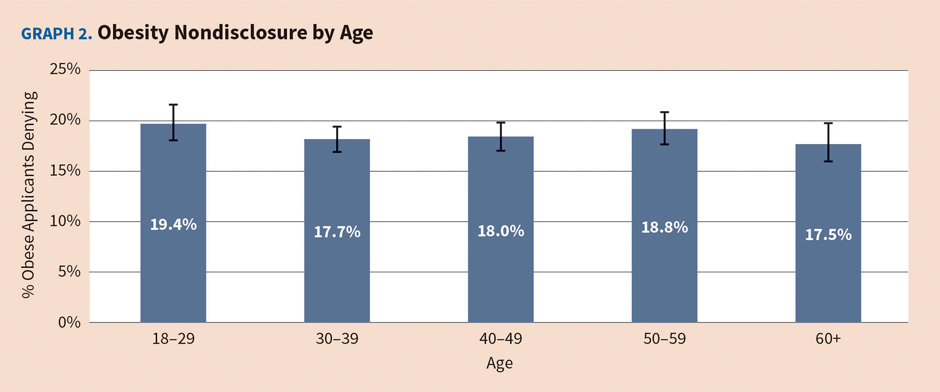

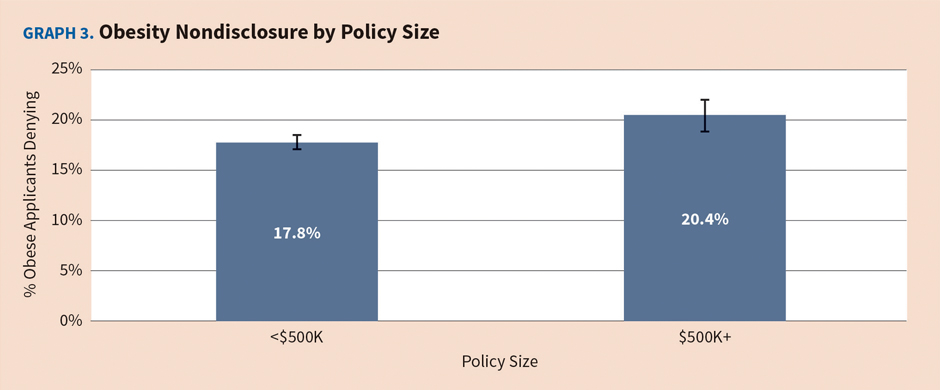

The percentage of obese (BMI>=30) applicants who claimed a BMI of less than 30 in the course of their tele-interview was 18.2 percent. Males were slightly less likely to disclose obesity, with a nondisclosure rate of 19.5 percent, as compared to 16.7 percent for females (see Graph 1). Nondisclosure was similar among all age groups, with the highest rate occurring among those 18–29 and the lowest in the 60+ population (see Graph 2). The effect of policy size was moderate, albeit statistically significant, with nondisclosure among policies of $500,000 or more exceeding that of smaller amounts by approximately 15 percent (see Graph 3).

Although our primary nondisclosure metric focused on the clinically significant BMI 30 threshold, morbidly obese (BMI 40+) individuals who misrepresent themselves as obese (BMI 30–39.9) also are of significance in mortality risk assessment. If this population is included among the nondisclosure counts, the overall population rate rises from 18.2 percent to 22.2 percent. More broadly still, if nondisclosure is defined as the under-representation of one’s BMI by at least one class, then nondisclosure was 33.6 percent in the morbidly obese, 20.7 percent in the obese, and 12.6 percent in the overweight.

Applicant HIV Nondisclosure

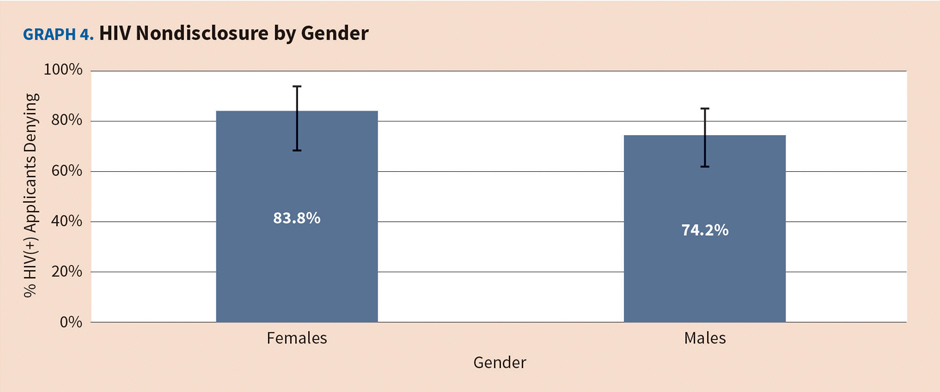

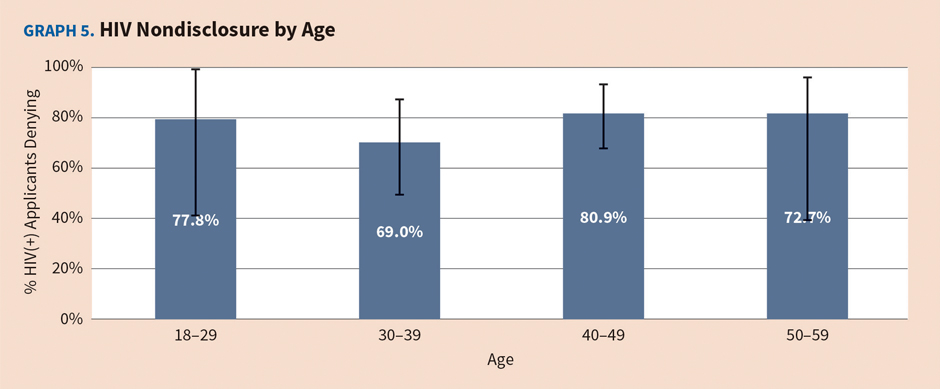

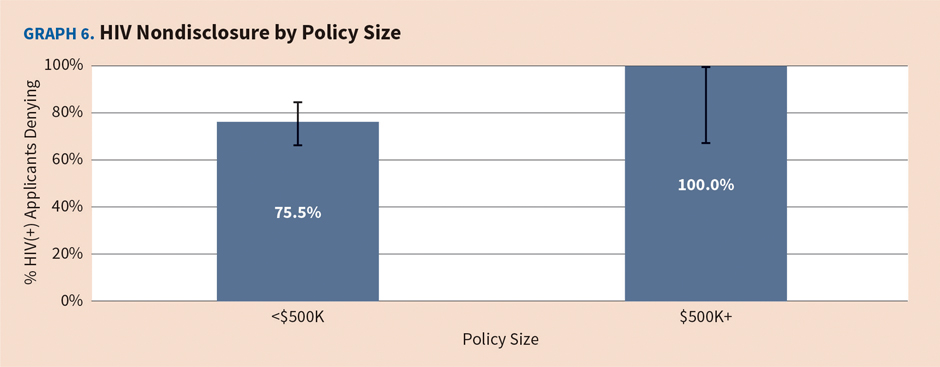

We analyzed 142,130 applicants between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2016, who completed a self-reported medical history tele-interview, which included a question regarding HIV status, followed by a paramedical examination that included insurance laboratory testing for HIV. Only 103 (0.07 percent) applicants tested positive for HIV, representing the effective sample size for nondisclosure analysis. The overall nondisclosure rate was very high at 78 percent (CI: 68.4–85.3 percent), while the difference between male (74.2 percent) and female (83.8 percent) nondisclosure rates was not statistically significant (see Graph 4). Sample size limitations restrict the power of our analysis to discern differences among age groups, but the available data do not suggest a substantial age effect (see Graph 5). A full 91 percent (94 out of 103) of HIV+ individuals applied for policies under $500,000, so policy size effects are particularly elusive. The nondisclosure rate for individuals applying for policies of less than $500,000 was near the population rate at 75.5 percent, while none of the nine HIV+ applicants applying for amounts of $500,000 or above disclosed their HIV+ status (CI: 66.4–100 percent) (see Graph 6).

Applicant Hepatitis C Nondisclosure

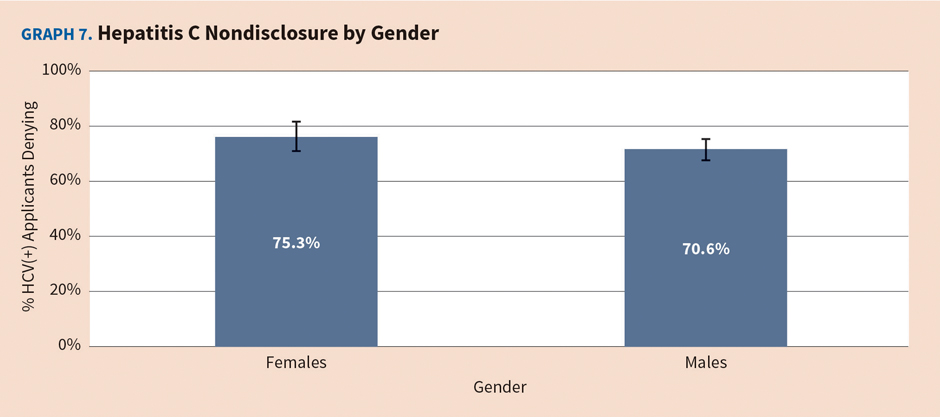

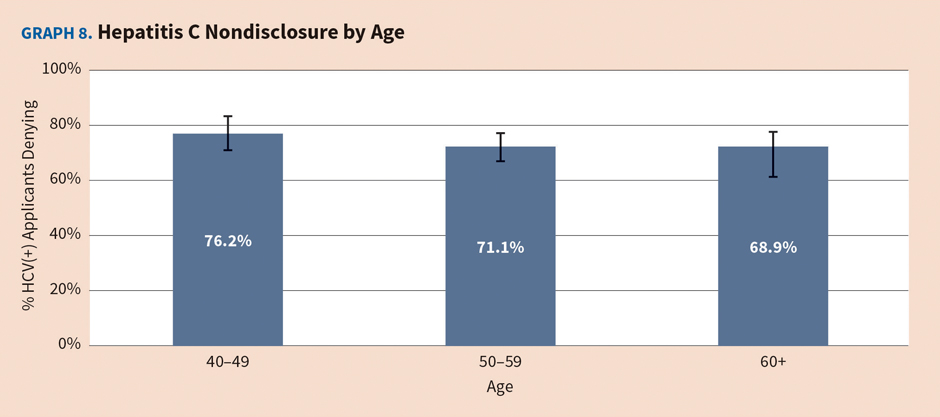

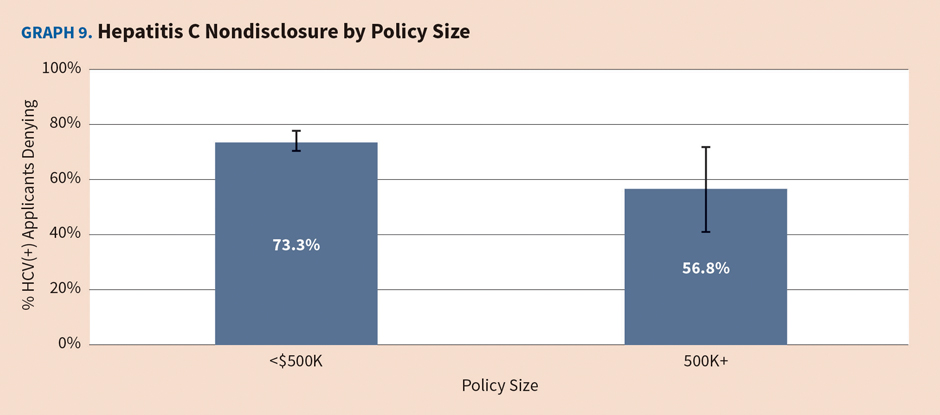

We analyzed 92,885 applicants between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2016, who completed a self-reported medical history tele-interview, which included a question regarding HCV status, followed by a paramedical examination that included insurance laboratory testing for HCV. A total of 752 (0.8%) applicants tested positive for HCV, representing the effective sample size for nondisclosure analysis. The overall nondisclosure rate was very high at 72 percent (CI: 69.0–75.5 percent), while the difference between male (70.6 percent) and female (75.3 percent) nondisclosure rates was not statistically significant (see Graph 7). Age effects were weak, but nondisclosure does appear to decline modestly with age, with rates peaking in the youngest (40–49) cohort and declining thereafter. A total of 94.1 percent (708 out of 752) of HCV+ individuals applied for policies under $500,000, but the higher policy amount sample size was sufficient to render the policy size effect statistically significant (see Graph 9).

Summary

The prevalence of conditions such as obesity, HIV infection, and HCV infection that are correlated with increased morbidity and mortality in the general population continues to be a significant factor in life insurance risk assessment. Accurate and reliable applicant self-reporting and confirmation of medical history is critical to the proper underwriting of applicant and population-level risks. Very high nondisclosure rates and information asymmetry appear to be taking place within the existing fully underwritten life market. Although the effects of reduced testing requirements envisioned in emerging paradigms such as accelerated underwriting cannot be completely understood, it seems reasonable to assume that any reduction in the probability of detection could increase the likelihood of nondisclosure.

JAMES PALMIER, MD, MPH, MBA, FLMI, is vice president and medical director for ExamOne.

BRIAN LANZRATH, MBA, is director of analytics for ExamOne.

Endnotes

[1] Palmier J and Lanzrath B; “Applicant medical and smoking history nondisclosure in the life insurance marketplace”; Contingencies; November/December 2016. [2] Ogden CL, et al.; “Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014”; NCHS Data Brief; November 2015. [3] Flegal KM and Graubard BI; “Estimates of excess deaths associated with body mass index and other anthropometric variables”; American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; April 2009. [4] Freedman DS, et al.; “Relation of body mass index and skinfold thicknesses to cardiovascular disease risk factors in children: the Bogalusa Heart Study”; American Journal of Clinical Nutrition; July 2009. [5] Finkelstein EA, et al.; “Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates”; Health Affairs; September/October 2009. [6] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; “HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas”; www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf. [7] Mirani G, et al.; “Changing trends in complications and mortality rates among U.S. youth and young adults with HIV infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy”; Clinical Infectious Diseases; December 2015. [8] Allison RD, et al.; “Increased incidence of cancer and cancer-related mortality among persons with chronic hepatitis C infection, 2006–2010”; Journal of Hepatology; October 2015.