By David Ingram

What do you think? Has the coronavirus rubbed our noses in it again? “It” being our inability to effectively identify and plan for the real risks.

Mega-catastrophes keep happening. We have lived through a tsunami that triggered a nuclear event, a 95%-plus drop in the market for tech stocks, an earthquake that leveled an entire city, a financial crisis that left large international banks afraid to trade with each other, and another that froze the markets of most of Asia.

Now, we face the trifecta of a deadly disease, self-imposed depression-like business closings and unemployment, and financial market meltdowns.

What these events all have in common is that they all have extreme consequences and they do not happen frequently enough for any of our beloved statistical techniques to apply.

When faced with these types of events, we would do well to retreat to Frank Knight’s famous distinction between risk and uncertainty—namely, quantifiability.[1] Much more recently, John Kay and Mervyn King “replace the distinction between risk and uncertainty deployed by Knight and Keynes with a distinction between resolvable and radical uncertainty.”[2]

But starting in the 1970s, psychologists and some economists have been telling us that we humans are poorly equipped to make any rational decisions about risk and uncertainty.[3] The new study of behavioral economics has shown that there are many biases and incorrect heuristics that govern our decision-making about risk.[4]

But we must be able to face everyday risk and resolvable uncertainty as well as radical uncertainty. And I believe that we can do that in a way that will provide us with acceptable, if not optimal, outcomes. To accomplish that, we need to cultivate and utilize risk intelligence.

“Our biggest problem as humans is ignorance, not malevolence. Ignorance is an entirely curable disease.”

—Jon Stewart

To define “risk intelligence,” I adapted a standard definition of intelligence:[5]

Risk intelligence is the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience in matters involving risk and uncertainty.

It reflects a capability for comprehending risk and uncertainty in our surroundings—“catching on,” “making sense” of things, or “figuring out” what to do in the face of both present and emerging risks.

Risk-intelligent people and organizations would:

- know when something is risky.

- know how to systematically determine drivers and parameters of risk.

- understand that those parameters do not fully define a risk. They identify a point on a gain-and-loss continuum.

A person with risk intelligence who works in a risk-taking organization:

- is able to identify the handful of risks that make up 90% of the risk profile (key risks) of an organization.

- understands the mechanisms that the company uses to maintain a consistent rate of risk for each key risk.

- can help to make sure that those mechanisms are maintained and only expect that there will be deliberately agreed changes to the rate of risk for any key risk.

- is able to understand risk/reward analysis and cost/benefit analysis where the trade-offs are often a certain reduction in earnings vs. an uncertain reduction in future losses.

- is aware of which risks the company is exploiting because he or she has the expertise and opportunity to make a good profit for the amount of risk taken and is able to notice when the opportunity to exploit has passed.

- is aware of which risks the company is accepting and carefully managing to achieve a reasonable profit while avoiding unacceptable losses.

- is aware of the risks that are unavoidable but that create little or no profits and that should be minimized at an acceptable cost.

- understands that people are generally optimistic and need to test plans against alternate future adverse scenarios.

Risk intelligence is what allows us to be able to assess danger from risk—as distinct from fear of risk. This is one of the most important aspects of risk intelligence that allows us to overcome some of the biases identified by psychologists.[6]

“Our intelligence helps us regulate our emotions. Fear, for example, is based on mistrust and a lack of self-confidence. If, on the other hand, we remain honest and truthful, open and tolerant, we will have greater self-confidence and overcome fear.”

—Dalai Lama

Risk intelligence also has a bias toward reality. As A. Conan Doyle put it:

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”[7]

The risk-intelligent will abandon an answer—and perhaps the model that led to the answer—when reality intrudes and presents solid evidence that the answer is incorrect.

“Risk intelligence is the strategic reincarnation of risk management.”

—Leo Tilman

As actuaries, we would classify ourselves as people with the capability to overcome fears and biases that might lead other people to make poor decisions about risk and uncertainty. Actuaries often possess risk intelligence. But not always.

People are not born with risk intelligence. It is acquired, sometimes as a byproduct of other activities but often deliberately cultivated. To produce the insights and capabilities listed above, risk intelligence needs to incorporate three elements: education, experience, and analysis. For risk intelligence that is needed to deal appropriately with radical uncertainty and the types of unexpected extreme events mentioned at the top of this article, a person or organization would need to bring all three elements.

Risk Education

There are two ways that education can help a person to develop risk intelligence and they relate to the two other elements. Risk education can provide information about the experiences of others with risks. While emotionally not anywhere near as powerful as own experiences, education (via case studies) is a far less expensive way to learn about ways that organizations can end up experiencing unexpected losses and other disappointments.

Some of the stories that you will likely hear are becoming cautionary legends that fill a similar place to stories like Aesop’s fables. One example is the story of the downfall of Barings bank.

Nick Leeson, the bank’s then 28-year-old head of derivatives in Singapore, gambled more than $1 billion in unhedged, unauthorized speculative trades, an amount which dwarfed the venerable merchant bank’s cash reserves.

He had made vast sums for the bank in previous years, at one stage accounting for 10% of its entire profits, but the downturn in the Japanese market following the Kobe earthquake on January 17, 1995 rapidly unraveled his unhedged positions.

Through manipulating internal accounting systems, Leeson was able to misrepresent his losses and falsify trading records.

This enabled him to keep the bank’s London headquarters, and the financial markets, in the dark until a confession letter to Barings Chairman Peter Baring on February 23, 1995, at which point Leeson fled Singapore and kickstarted an international manhunt. Three days later, Britain’s oldest merchant bank, founded in 1762, ceased to exist.[8]

This story has been told over and over in the past 25 years as a cautionary tale, just like the old fairy tales that cautioned European children for centuries.

The second way that risk education helps with risk intelligence is to teach analytical techniques. The best education to support analysis would include when an analytical technique is appropriate to use as well as the shortcomings of techniques under a variety of situations.

Risk education can be obtained in either formal or informal processes. A formal program is usually offered by an educational institution; completion of the program usually results in the conferring of a designation.

For example, Columbia University offers a Master of Science in Enterprise Risk Management. This program, founded and led by an actuary, Sim Segal, offers courses in management and assessment of financial, insurance, operational and strategic risk, including ERM framework, risk governance, and the full risk management cycle (identification, quantification, decision-making, and communication). It also provides a comprehensive look at a very wide range of risks, including insurance, financial, operational, and strategic. Segal will tell you that “60% of the big threats to firms relate to strategic risks.”

The actuarial profession’s Global CERA credential is another example. To obtain the CERA, actuaries must learn about seven areas of risk management:

- ERM concept and framework

- ERM process (structure of the ERM function and best practices)

- Risk categories and identification

- Risk modelling and aggregation of risks

- Risk measures

- Risk management tools and techniques

- Capital assessment and allocation[9]

In both programs, learning about how to analyze risks is an important component. In the Columbia program, risk evaluation is centered on the idea of the value of the organization. Segal, the director of the Columbia program, says that choosing the right risk metric is extremely important. He suggests using a “value-based ERM approach—a synthesis of value-based management and ERM—which measures risk as deviation from what the organization values, such as company value for corporations. This generates buy-in and aligns ERM with strategic planning and decision-making in general.”

In addition, the Columbia program employs almost all experienced practitioners as professors, who can pass along their versions of the stories and legends of famous risk management misadventures.

Risk Experience

“You don’t learn to walk by following rules. You learn by doing, and by falling over.”

—Richard Branson

“All men make mistakes, but only wise men learn from their mistakes.”

—Winston Churchill

ERM is growing out of a sort of settlers vs. pioneers situation. Pioneer chief risk officers (CROs) were the first to have that position at their companies. They had nowhere to learn their craft except through the school of hard knocks. ERM was a new discipline and they were inventing it as they went along. And if you would ask many in that first generation of CROs, they would tell you that is the only way to learn the job—by hard experiences.

There is a lot to be said for this argument. You certainly read about the problems in financial markets when the generation who lived through the last bear market all retire and leave the floor to youngsters who have no fear.

And while behavioral economics has garnered an economics Nobel Prize for dissecting the problems with human financial decision-making, you have to understand experimental psychological methods to realize that what they are describing are the mistakes of the totally inexperienced. They usually work to minimize the “Practice Effect”:

“Sources of practice effects include deliberate rehearsal, incidental learning, procedural learning, changes in an examinee’s conceptualization of a task, shift in strategy, or increased familiarity with the test-taking environment and/or paradigm (i.e., ‘test-wiseness’).”[10]

So as you would think, it is likely that experience (i.e., practice) would be one way of avoiding the behavioral economics problems.

Other psychologists, most notably Gigerenzer and Klein, see the glass as much more than half-full. They each see that good heuristics are a major source of the hegemony of humankind over the globe. Klein studied decision-making of experts and observed an approach that can serve as a good general model of how an expert brings their experience into decision-making in his book Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Klein discovered that experts do not typically use a slow, rational process that is taught in decision-making and logic classes. Their “natural” process is to study the problem against one solution quickly selected from their mental “library,” which has been constructed over years of experience. If, upon closer examination, that solution appears unworkable, they seek to improve it or identify another solution that would pass the test that the original solution failed. At the end of their analysis, they have a solution that works under all the conditions that their study anticipated.

Risk Analysis

I am not at all sure when models and risk assessment became synonymous with risk management. Certainly Peter Bernstein in his very popular book Against the Gods in 1998 equated the development of mathematical, statistical models of risk with the advancement of risk management. Certainly there are many situations, especially those that are encountered by financial institutions and insurers, where a pretty high degree of analysis is needed just to see what the actual problem might be.

When I was the ERM specialist for Standard & Poor’s in 2005, at least 25% of the insurance risk managers who I talked with told me that at their company, ERM was synonymous with ECM (economic capital model).

Evans states that “the ability to estimate probabilities accurately[11] is risk intelligence in his book by that title.

Proper risk analysis is important because risk is often complicated. Kahneman talks of slow System 2 systems that avoid some of the biases commonly found in fast System 1 thinking.[12] Actuaries are trained to always use System 2 thinking, which may produce a higher chance of a correct conclusion, but the slow System 2 analysis and thinking process might mean that conclusion is not available until after a business decision has been made.

The current COVID-19 pandemic provides examples of the value of risk analysis. Aggregate total figures for number of people infected and deaths from the pandemic are regularly reported and widely quoted. But after some weeks of almost global quarantine of mostly well, uninfected people, complaints started to emerge. I was sitting in New York, in the town of New Rochelle, the first place in the U.S. to go under a sort of quarantine order and the restrictions all seemed reasonable to me (using System 1 thinking). But when I engaged System 2 and found state-by-state data, I realized that things were very different in different places. My analytical training told me to dig further, though, and I started looking at COVID-19 cases per capita and found that some of the states with low case counts had low populations and higher-than-average per capita case counts.

Analysis of risk involves deconstruction of a problem into its components and determining the drivers of each component and eventually the range of possible inputs and outputs from each component. But it also involves recognizing how those components all work together—the systems aspects of the situations.[13]

Criticisms

There are many criticisms of each of these three aspects of risk intelligence. Above, I mentioned the settler vs. pioneer issue. The pioneers are often very critical of the unrealistic book knowledge of those who come to a risk management job with a degree or certificate and no experience. Some of this issue can be tracked back to an academic community that sometimes provides education in a theoretical bubble without sufficient grounding in the real world.

A simple example of this is the Nobel Prize-winning Black-Scholes-Merton model. Many, many texts and academic papers say that it is used to price derivatives. But for many years, only rarely was it mentioned that the key parameter for such pricing is implied volatility, which is determined by examining market prices. So BSM has been used more to extend market prices from observed prices to similar securities, a much smaller lift. And when practitioners found that it sometimes missed systematically, they invented the “volatility smile” to fix the BSM results.

Complex risk models are criticized by Kay and King, who suggest that “the world of economics, business and finance is ‘non-stationary.’”[2] And they suggest that all of the extreme events such as those at the top of this story are all unique events that are never repeated and are different enough that statistical techniques are not helpful.

COVID-19—Relying Upon Education

The current situation, in the middle of a pandemic, provides an example. Complex statistical risk capital models are widely used in ERM programs to provide consistent measurement of a wide variety of risk exposures separately and in combination under a very wide range of situations. We know exactly how to model the course of a pandemic, but in our current situation, we do not yet know the correct parameters for COVID-19. Analysis can provide some hints, but the data available is corrupted by political concerns and resource issues.

Experience also provides little help, because the last major pandemic was over 100 years ago.

But because we allow for three sources of risk intelligence, we are left with education—and there we find some help. The year 1918 is not just like 2020, but we can find some useful stories to help us make choices.

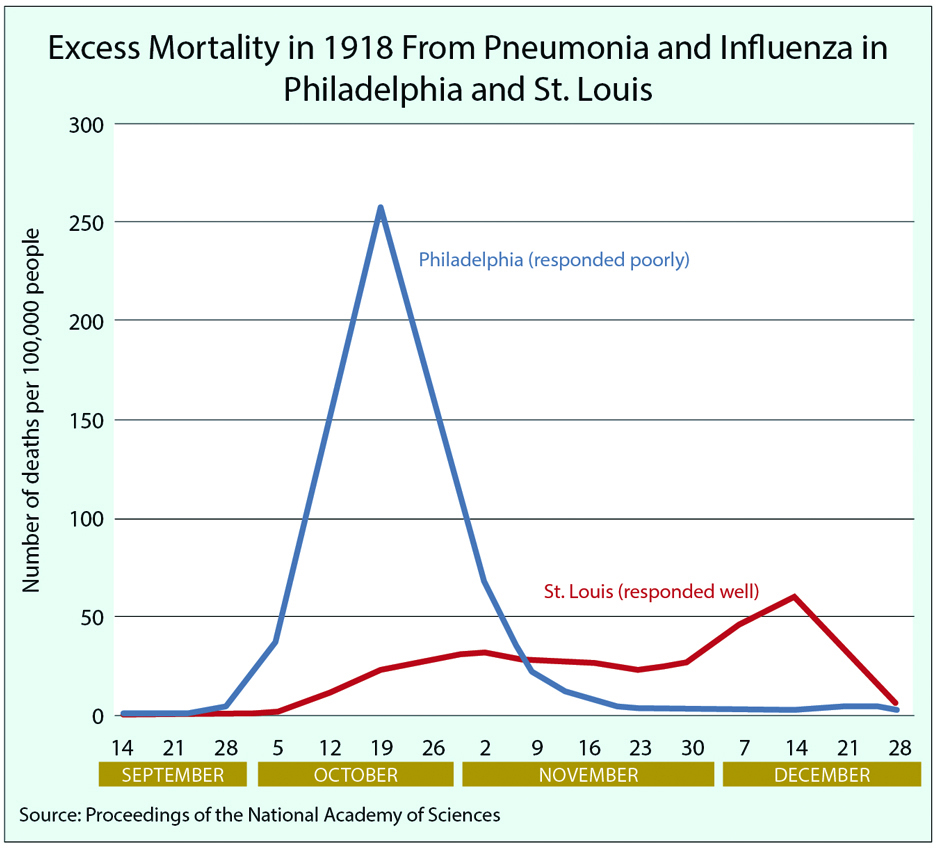

For example, there is the story of how Philadelphia and St. Louis celebrated the end of World War I. Philadelphia had a parade attended by hundreds of thousands of citizens, while St. Louis chose to institute a “social distancing” program. Incidence of influenza was much lower in St. Louis.[14]

COVID-19—Relying on Analysis

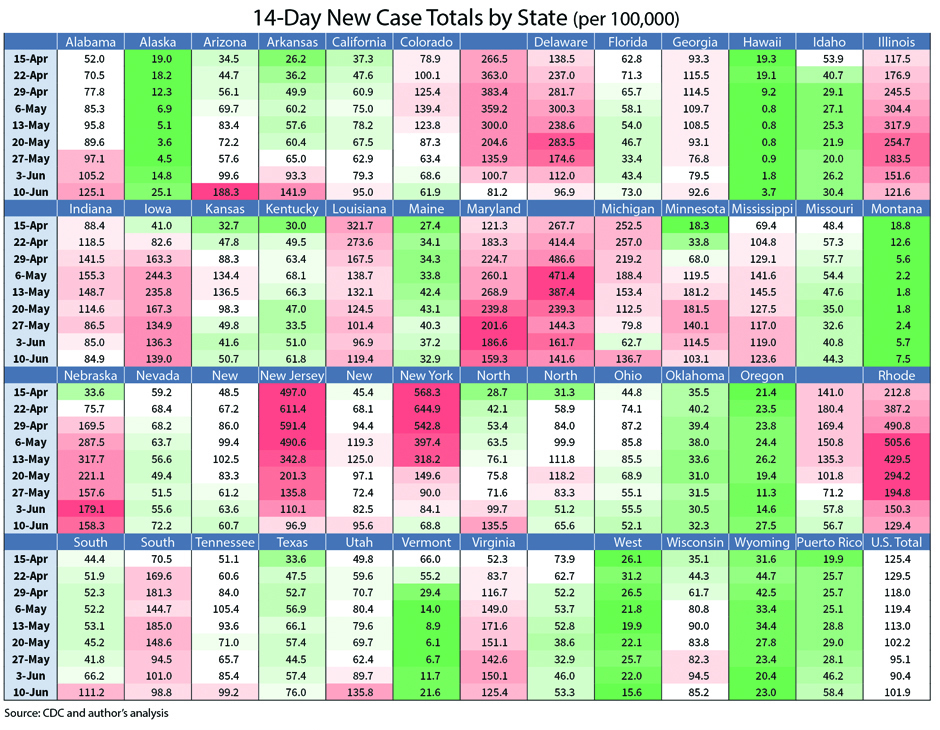

While we do not have the reliable data to predict outcomes for COVID-19, analysis can still play an important role in managing that risk. Analysis is necessary when the situation is too complex for the human mind to keep all the aspects straight in our heads. An example of this is the way that we initially sought to apply the exact same treatment—closure of schools and businesses with a stay-at-home order—throughout the country. Anecdotal evidence suggested that this might be overkill in some places. Analysis can show that there is quite a significant difference in the incidence of infection in different states.

With 50 states, some with improving experience and others deteriorating, careful analysis is needed to see the actual situation. The table on page 18 shows weekly values for new cases from the prior 14 days at each point, per 100,000 population in the state. That last part—putting the values on a consistent basis, instead of focusing only on case counts—has only been available from the CDC since late May. And at least 10 states that have stayed green (meaning that their new case totals are among the lowest of the 50 states) for the nine weeks of this study. Other states have been in the red for the entire time.

This analysis shows a drastically different level of COVID-19 infections in different states. Many states have used numerical criteria to decide when to lift the stay-at-home rules. It is likely that it would have been valid to have applied the same sort of criteria when deciding to close the state.

COVID-19—Relying on Experience

When we refer to relying on experience for risk management, what usually comes to mind is relying upon Kahneman’s System 1 thinking, more commonly called “gut instincts.” In the case of COVID-19, there are few experiences that would provide the basis for the “from the gut” decisions, so those types of conclusions should be viewed with caution. But an experienced risk manager will have a different “gut reaction.” Their experience will tell them that management of a risk, even a risk with “radical uncertainty,” needs to be done with a careful feedback loop. The risk manager will plan mitigation activities; set plans for risk taking and expectations for outcomes; implement a system of tracking experience; periodically review the outcomes; and make adjustments for the next period to mitigations, risk-taking plans, and expectations for outcomes based upon emerging experience. This is the fundamental basis of risk management, and the experience of the risk manager tells them that it can be applied to COVID-19.

In the tables on page 18, there are several states where the shading changes over the nine weeks. Sometimes git goes from red to white (neutral). In other cases, the experience goes from green or white to red. In those cases, the risk manager needs what Tilman and Jacoby call …

Risk Intelligence and Risk Culture

Some of the sources that have been mentioned talk about risk intelligence as an individual trait, but others talk about it as an organizational characteristic. Another way of saying that it is an organizational characteristic is to say that it is a part of the culture—that the culture values each of education, analysis, and experience and has the custom of examining situations from all three perspectives.

“Business communications and interaction skills are really critical to making you a successful ERM professional.”

—Sim Segal

To keep risk intelligence as an important part of the culture, the risk manager needs to constantly communicate about the basis for the risk-related decisions as well as the findings and adjustments that come from the risk feedback loop. Communications skills are key to making that process work.

Ultimately, if the culture does not support and value risk intelligence, then decisions will be made that go against risk intelligence but that support other values that are important to the organization.

DAVID INGRAM, MAAA, FSA, CERA, is executive vice president with Willis Re in New York.

Endnotes

[1] Knight, Risk Uncertainty and Profit, 1921. [2] Kay & King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020 [3] Kahneman & Tversky, Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk, 1979 (Among many others) [4] Stavenson, Predictably Irrational—Applying behavioral economics to actuarial science, Contingencies, 2019 [5] Gotfredson et al, Mainstream Science on Intelligence, 1994 [6] Stevenson, Predictably Irrational, Contingencies, Jan/Feb 2020 [7] Doyle, Sign of Four, 1890 [8] Smith, The Barings collapse 25 years on: What the industry learned after one man broke a bank, CNBC, 2020. [9] CERA Global Association website, Syllabus, accessed 29 May, 2020. [10] McCabe D., Langer K.G., Borod J.C., Bender H.A. (2011) Practice Effects. In: Kreutzer J.S., DeLuca J., Caplan B. (eds) Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. Springer, New York, NY. [11] Evans, Risk Intelligence, 20125 [12] Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow, 2011 [13] Cantle, Ingram, Actuarial Thinking, The Actuary, 2012 [14] Richard Smith, The BMJ, 2007.