By Wes Edwards

It was widely reported earlier this year that the so-called Doomsday Clock was moved closer to midnight by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.[1] It is 2½ minutes till midnight “largely because of the statements of a single person … the new president of the United States,” board members reported, closer than at any point since 1953—and so, according to the Bulletin, we are closer to doomsday and the end of human period on Earth.

Doomsday as a scenario is not of much interest to insurers. No one is willing to pay a premium for a benefit for which no one would be left to receive. Thus, there is little point in assigning a dollar value to it. Yet such a scenario is arguably more important than any risk facing the Earth.

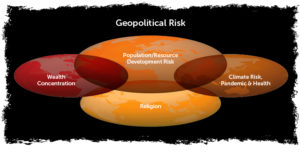

While atomic and nuclear destruction have been the focus of the Doomsday Clock and its Bulletin technicians, the world has increasingly recognized other emerging threats to humanity. Geopolitics, overpopulation, religious fanaticism, wealth concentration, pandemic/health care risks, climate change/global warming—all are threats to humanity. These forces are not likely to destroy the world, but each of these risks has the potential to destabilize the planet in ways that increase the threat of nuclear annihilation. Furthermore, a convolution of these risk factors may increase risk in unforeseen ways.

As an actuary, the risks we evaluate daily have a direct bearing on political discussion, and therefore on the risk of global destabilization and doomsday. What follows is a brief summary of those risks and how they might destabilize the planet such that a doomsday scenario becomes possible.

Geopolitics

The election of nationalist and populist leaders by electorates that view immigrants and outsiders as threats to their own well-being and prosperity threatens diplomacy and cooperation among nations. Since Machiavelli wrote The Prince in the 16th century, the balance of diplomacy and war has tipped toward diplomacy, though not without notable steps backward. But the advent of the atomic age in 1945 has raised the stakes for humanity. I believe the new nationalistic fervor—especially in developed countries and world powers—is the single most significant non-weapon-related factor already considered by those keeping the Doomsday Clock.[2]

How could it not be, given the impact on treaties, ongoing wars, and foreign relations?

When the smallest, poorest, and most undemocratic of nations have nuclear weapons with the ability to deliver them anywhere, the calculus of doomsday risk has clearly changed. Those nations are now in a position to impose demands on the rest of the world and expect that those who have more to lose will be less willing to “call their bluff.” The likelihood is increasing that a bluff called or a bluff overplayed will result in cataclysm.

Population

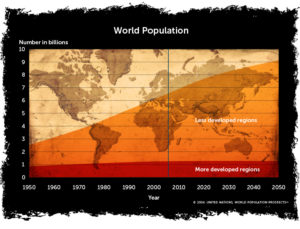

The world’s population has continued its rapid growth, but the growth has not been equally distributed. The table on page 31 from the United Nations shows that developing regions have experienced the lion’s share of the population growth, with more outsized growth projected in the coming decades.

Most of the “hot spots” in the world where civil war, revolution, and religious conflicts exist are found in developing nations. Not surprisingly, this correlation points to growing population as a risk factor as populations with differing political, religious, and cultural attitudes bump up against each other, resulting in conflict.

Furthermore, even small localized conflicts have proven capable of rapidly expanding to neighboring areas and populations as alliances and religious and cultural ties link the indirectly impacted to those in the hot spot. World War I was the classic example of a localized conflict ultimately embroiling the world. It is not difficult to envision that mutual self-defense organizations such as NATO, which are structured to deter war by raising the consequences of attack on one member, could turn a regional conflict into a cataclysm. This risk is greater if an aggressor doubts the willingness of members to truly come to one another’s aid if attacked.

Religion

Without a doubt, the intent of the world’s major religions is to bring peace and spiritual fulfillment throughout the world. However, collectively they have not prioritized the ability for each religion to reconcile the means of achieving that intent with the goals and means of other faiths. Since the Crusades, differences between religious groups have been a source of conflict, and this dynamic continues today. The nuclear states of Pakistan and India represent another example of national religious differences driving military conflict that has greater potential ramifications than 20 years ago.

Another religious risk factor, ironically, is the decline of religion in the developed world. As reported by National Geographic:

The religiously unaffiliated, called “nones,” are growing significantly. They’re the second largest religious group in North America and most of Europe. In the United States, nones make up almost a quarter of the population. In the past decade, U.S. nones have overtaken Catholics, mainline Protestants, and all followers of non-Christian faiths. …

But nones aren’t inheriting the Earth just yet. In many parts of the world—sub-Saharan Africa in particular—religion is growing so fast that nones’ share of the global population will actually shrink in 25 years as the world turns into what one researcher has described as “the secularizing West and the rapidly growing rest.”[4]

What are the implications of the growing atheistic, agnostic, secular, nonreligious population in Europe and America in the face of a religious less developed world?

Wealth

The concentration of wealth and the influence of wealth and business have continued to emerge as a global force. Some political corners and consumer forces pressure wealth to be “responsible,” but the economic appeal of new low-cost sources for labor as input and beckoning markets of consumers for output mean capital will seek the highest return on investment. The aforementioned nonreligious European and North Americans represent less than 15 percent of the world population but control over half of its wealth.

Extremist organizations appealing to religious beliefs constitute evidence of dissatisfaction in the wealth and power status quo that spill over with destabilizing effect on the developed world. The destabilization may be in the form of terrorism, refugees, and migration crises. The likelihood appears great that these forces and similar events will continue in frequency and magnitude given that wealth concentration and religious and secular sentiment against it continue to grow.

Pandemic and Climate Change

Since before the millennium, actuaries have discussed climate change on the pages of Contingencies, in professional meetings, and within insurance companies. The consensus has been that there is sufficient evidence to conclude that “a risk” exists.[5] The debate continues, but differences of opinion are mostly about the timetable and geopolitical implications of climate-related events.

In 2005, the avian flu epidemic drew comparison to the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918.[6] Whether a version of Ebola, Zika, or avian flu—or some unforeseen new disease—takes the form of a rapidly spreading and uncontainable pandemic, we know that history shows nature’s capacity for disease to periodically manifest in unpredictable ways with which medical science is not always able to contend. In addition, the complicating risk factors of human and animal population density and proximity are growing with population and wealth concentration growth.[7]

High-quality public sanitation and health care are dependent upon wealth, and the divergence of wealth from areas with the greatest fertility rates and therefore the greatest changes in population density further point us toward risk where pandemics and resulting political instability are most likely to arise. From the Black Death of the Middle Ages to influenza in the early 20th century to Ebola and Zika today, the connection between public health and geopolitical events is well documented.[8]

Risk Factor Interaction

Understanding the interaction of risk factors is a critical step toward mitigating the threats that they pose. Geopolitics both influences and is influenced by all of the other factors due to the increasingly global nature of the threats and impact of each. The economic impact of business is global; migration of populations means population and resource development differences are global and that religious differences are ever-present; and the impact of pollutants and emissions in one part of the world is readily shown to have an impact, often unexpectedly, in other neighboring and distant parts of the world.

With regard to wealth and its concentration, doomsday risk management requires:

- An understanding of how it impacts religious leadership and doctrine;

- A thoughtful approach to climate risk—where wealth concentration is low, the poor have no ability to reduce carbon footprint; where it is high, we find disproportionate consumption; and

- Conscious mitigation of its impact on health care, family planning, population movement, and resource development risk.

- Regarding destabilizing pandemic/health factors, the risk posed is very challenging to quantify, but epidemiologists insist there are threats to materialize globally, despite the recent containment of avian flu and Ebola. More awareness and attention is needed on the past and possible future implications of:

- Global pandemics as clearly destabilizing threats to social order filled by violence, looting, and public unrest, as seen during the 20th-century influenza and 14th-century plague;

- The impact on stability from religious precepts in the face of death on a vast scale; and

- Disproportionate impact of regional (nonglobal) pandemic that may impact regional stability and geopolitics.

Climate change is already affecting population migration, resource allocation, and development in the form of extended droughts, famine, and resource decline—and resultant record numbers of displaced people, refugees, and migrants. One study presciently suggested in 2013 that the Arab Spring could be reversed due to failure to address the resource challenges from climate change. The report cites climate models that show warming will occur faster in the Middle East-North Africa region, exacerbating regional water scarcity.[9] If population outlet valves are closed and climate change mitigation efforts are unsuccessful, geopolitical stability may be expected to deteriorate.

Population growth—the sheer impact of human numbers in a finite location—is sufficient to tip population density to a point where stressed agricultural, mineral, and forestry resources cannot support humanity. At this point, disease and sanitary health risks grow and pandemic risk increases. Even without population growth in a region, the impact of climate change driven by human behavior in the rest of the world may dictate a decline in the regional population. These events are obviously destabilizing, with potential geopolitical ramifications.

Conclusion

This is by no means a complete list of risk factors, nor a full description of each, nor does this discussion begin to explore the interactions of the listed risk factors. What seems clear from a brief view of the risk landscape, though, is that the number and magnitude of risk factors are continuing to grow and to compound each other, while the willingness—if not the ability—to address them is not keeping pace with that growth.

Each of the risk factors identified here is greater today than when the Doomsday Clock was created. The consequences are high, and the need to model and understand the risks is great. While actuaries may be able to do more to quantify and publicize the nature of these risks, true leadership will be required to mitigate them. Without such modeling, discussion, and leadership, doomsday—once solely rooted in the dystopias of science fiction—is by no means inconceivable.

WES EDWARDS, MAAA, FSA, is a principal at Mercer based in Louisville, Ky.

Endnotes

[1] “Doomsday Clock Moves Closer to Midnight”; New York Times, Jan. 26, 2017.

[2] “Timeline”; Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists website. Accessed at thebulletin.org/timeline on Aug. 15, 2017.

[3] “World Population to 2300”; United Nations’ Economic & Social Affairs; 2004.

[4] “The World’s Newest Major Religion: No Religion”; National Geographic; April 22, 2016.

[5] “The Global Warming Debate Heats Up”; Contingencies; November/December 2000.

[6] “Pandemic—The Cost of Avian Influenza”; Contingencies; September/October 2005.

[7] “What 11 Billion People Mean for Disease Outbreaks”; Scientific American; Nov. 26, 2013.

[8] The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History; John M. Barry; 2004.

[9] Underpinning the MENA Democratic Transition—Delivering Climate, Energy and Resource Security; E3G; February 2013.