By Sam Gutterman

In these days of a pandemic, climate change, super-high unemployment, and low interest rates, it can be difficult to maintain that future events can be represented by probability distributions. Shocks due to unanticipated disruptions and not-well-behaved trends contribute to this skepticism.

Outlier events will always occur. I remember my intense running days, for example, when in Peoria, Ill., a 100-kilometer race reached -60oF windchill, or a Milwaukee marathon on a 95 day (95o and 95% humidity)—or when, as president of the Chicago Area Runners Association, I had to call off a 5K corporate team race with more than 5,000 runners due to health concerns on a 90 oF day. The race’s medical director and I thought the event would be too dangerous for some of the 60-year-old out-of-shape CEOs.

Frequency, severity, timing, and preparedness—all important factors to consider, both individually and in aggregate.

Some disruptions are sudden, like a pandemic, or slow-moving, like sea-level rise. We are pretty sure the latter will occur, but its timing and severity are uncertain.

Some of the most difficult conditions are affected by human behavior or actions, notoriously difficult to model—such as the rapid introduction of e-cigarettes or the slow but seemingly inexorable increase in obesity prevalence. Some systems are seriously complex and nonlinear, with a chance of disruption.

Of course, not every contingency that actuaries face is subject to such disruption, but many are. I recall a book on risk that stated that there is no uncertainty in mortality. In contrast, I think mortality forecasting over the long term is hugely complex. It can be difficult to understand our current situation, let alone the future. Although I respect many mortality models, none of them that I am aware of picked up the slowdown in mortality rates in many countries between 2010 and 2018—was this period a blip or a discontinuity? Another example is the difficulty in attributing many deaths to COVID-19; developing a case fatality rate is dependent on the accuracy of the number of reported COVID-19 cases, as well as proper attribution of deaths to cause.

For many years, I floored my interest rate probability distributions at zero or a small number, As I presumed that the frequency of negative interest rates would be insignificant, and even then, only applicable to short-term instruments. In May, there were 3-year negative UK bond yields, and the Fed chair had to publicly state he was not in favor of negative interest rates to assuage financial markets.

Especially after COVID-19, life doesn’t seem as controllable or estimable as it did. Complacence and reliance on inertia no longer feel like “best practice.” We can no longer deny possibilities out-of-hand, even if we can’t determine with much confidence the probabilities involved. Stockpiling food against something disastrous may no longer seem ridiculous.

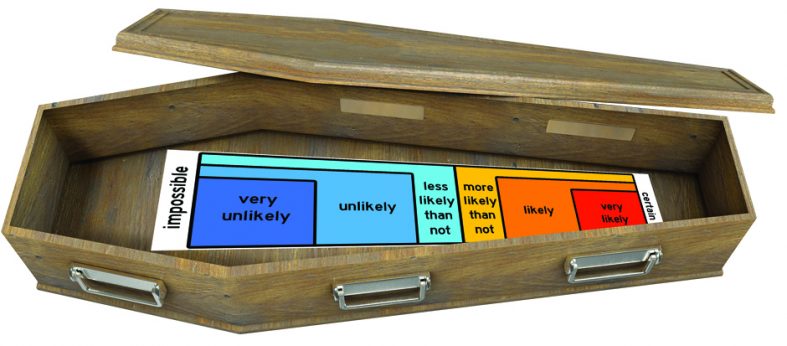

So far, I have ranted about disruptive outcomes, but isn’t there anything to be said for the use of probability distributions? I do believe that some issues can be adequately explored through probabilistic models (risk), while others that seemingly cannot be assigned probabilities need more, such as scenario or sensitivity analysis.[1] A qualitative assessment is always needed, driven by an understanding of the risks and their interactions involved. Risk tolerance and an assessment of possible countermeasures (e.g., mitigation and adaptation) are necessary components of any such analysis. Remember the old adage: If you can’t measure something, measure it anyway.

We as actuaries need to examine and understand possible drivers and consequences of the tail in these distributions. Our current understanding of the tail is usually inadequate. Tail scenarios should not be ignored; in many cases, a rigorous sensitivity analysis is called for—possible threats must be managed. Yet a price for risk and uncertainty needs to be assessed (e.g., in insurance financial reporting and project analysis) and a risk adjustment is needed, possibly by means of a combination of a statistical technique and consideration of the effect of alternative scenarios, including the disruptive effects of a pandemic or environmental disaster. We need to reassess all of the risks we or our clients undertake to distinguish between risk and uncertainty and the best methods to address each. Although the use of probability is not really dead, its limitations need to be recognized.

Reference

[1] For a much longer discussion, see Sam Gutterman, “Risk and Uncertainty,” a chapter in the International Actuarial Association’s Risk Book..