By Andrea Huckaba Rome | Illustration by Bruce Macpherson

In August 2019, Netflix introduced a documentary series called Diagnosis. In each episode, the viewer is introduced to a patient with serious medical symptoms—symptoms that are a mystery to local doctors. In the first episode, the long-suffering patient, a young woman named Angel from Las Vegas, had been searching for answers to an unknown malady for years. She had incurred enormous medical debt and was no closer to understanding or managing her debilitating pain.

Enter Dr. Lisa Sanders, a Yale New Haven Hospital physician with a long-running New York Times Magazine column on mysterious medical symptoms and their ultimate diagnosis. She explains that a correct diagnosis is critical because “you’ll never get the treatment right if you don’t have the right diagnosis.”

In the series, Dr. Sanders provides case details of her selected patient and encourages response from her New York Times readers—“the crowd.” In episode 1, she details why this method works:

“One of the tools that doctors use are the other doctors in the room. And whether you’re going to get a diagnosis or not really depends on who’s in that room, and who might see something that they recognize and understand and then identify it. So what we’re doing is just making the room that much bigger. More people, more experience.”

The response from readers is overwhelming. The column receives replies from physicians and ordinary folks all over the globe. The basic pattern of responses was:

- “Sounds like you have what I have. I was diagnosed with—”

- “My family member has this. We can’t figure it out either, but the doctors have it narrowed down to these diagnoses:—”

- “I am a physician in the field of —, and it sounds like you might have something in the — family of diseases.”

- “Based on a cursory internet search, I think you have—”

- “I have no idea what you have, but I wish you well, and hope you find an answer.”

Ultimately, Angel was invited to Italy to be diagnosed by a team of specialists who had responded to Dr. Sanders’ description. They ran the tests for no charge, courtesy of the Italian medical system, which is mostly publicly funded. The final diagnosis was a rare genetic metabolic disease that many nonphysician respondents had identified in response to Dr. Sanders’ initial query. This diagnosis was good news: Angel’s symptoms could be managed with a change in her diet.

This seems a fairy-tale ending to a medical mystery. Credits are scrolling. Autoplay is counting down to the next episode and my husband is reaching for more popcorn. But in my actuarial brain, there are more questions:

- How much money could have been saved if the diagnosis had been made nine years sooner?

- Why had this woman’s doctors not done more for her? Had the U.S. medical system failed her?

- How widespread is crowdsourcing in medicine? Does it have a high success rate?

- How large should the crowd be to be effective? Should the respondents have medical expertise?

- Is crowdsourcing covered by insurance? Should it be? How would actuaries rate for it? Would respondents be compensated?

- What are the legal issues? Privacy concerns? Malpractice woes?

Let’s dive into what we know.

Current Medical Crowdsourcing

CrowdMed

A brief search revealed that Dr. Sanders is not the only physician experimenting with the brave new world of internet diagnosis. An online service called CrowdMed[1] offers a similar approach. Patients seeking a diagnosis to a mystery ailment can upload information about their medical history and current symptoms. In return they receive a list of potential diagnoses, ranked from most to least probable based on an algorithmic assessment and crowd opinion. The goal with CrowdMed is to expedite the time it takes to find a correct diagnosis.

CrowdMed is accessed through a tiered payment system for patients that ranges from $149/month to $749/month for the service. A discount is provided if the patient uploads current medical records and/or images. The higher tiers offer a greater number of opinions and limit responses to those from higher-ranked physicians. The patient is also encouraged to offer additional dollar incentives to attract physicians to their case. This service can be provided to employees as an employee benefit, and is also an eligible health care expense using a Health Savings Account (HSA) or a Flexible Spending Account (FSA).

On the other side of the equation, licensed physicians, medical students, physician assistants, chiropractors, scientists, naturopaths, and health care aficionados can sign up to be medical detectives. They review the uploaded cases and offer their assessments. If they are a successful detective who provides useful information, they are paid for their efforts. As their “wins” increase, they are invited to participate in more complex cases—and compensation increases.

According to CrowdMed stats from 2019 FAQs, the detectives are predominantly male, 60% work in or study medicine, and the average age is 36.

So, does it really work? According to Dr. Sanders, getting more detectives “in the room” will increase the likelihood of a correct diagnosis, especially in difficult cases. Does CrowdMed data support this theory also?

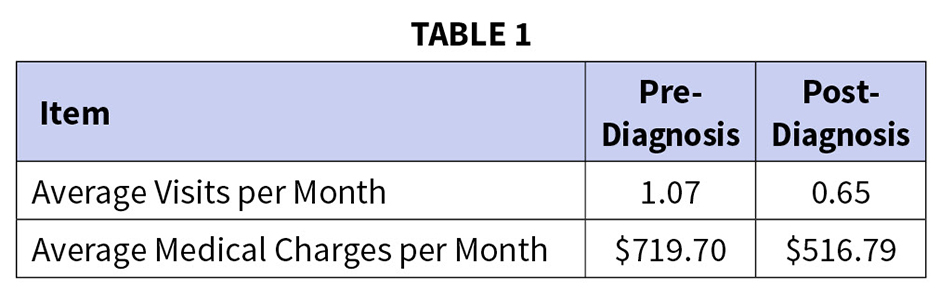

A paper was published[2] in 2016 examining the impact of a correct diagnosis on health care visits and overall cost incurred by the patient. The study reviewed claims data for patients who used CrowdMed, before and after a correct diagnosis. It found that frequency of provider visits was significantly lower after resolution of a case on CrowdMed. The study also found that medical charges were lower after case resolution. See Table 1 for the study’s findings.

This study only had a small number of participants, so it should be regarded only as a case study. Similar studies using CrowdMed data have returned directionally similar results.

CrowdMed cites its own success. It claims that, of the resolved cases, 60% of patients were led closer to a correct diagnosis or cure. Additionally, 75% of medically diagnosed patients had their CrowdMed diagnosis confirmed by their physician.

Other Crowdsourcing

Apart from the methodologies used above for finding a diagnosis, there are many other crowdsourcing techniques being used in medicine currently. A few are highlighted below. The full list was in a review of medical crowdsourcing published by the Journal of Global Health in 2018.[3]

The chart highlights just a few of the many examples of crowdsourcing being implemented. Some observations from the review article:

The crowd, on average, is more accurate if there is a gaming element. This is true even if the crowd is comprised of “experts.” Similarly, crowdsourcing competitions, including those using machine learning tools, are generally successful.

The crowd is more accurate if it is more diverse. One particular method in the review article did not perform well when all the respondents were from the same university.

It is important to evaluate crowd responses using a threshold of correctness, or a degree of trustworthiness. Such controls remove noise and crowd members who are not reliable.

Benefits and Drawbacks

Some benefits of crowdsourcing:

- Increasing the number of experts in the room. Rarely does medicine have a single “right” answer. Gaining multiple (qualified) perspectives on a case is similar to obtaining a second opinion. It may be less time-consuming, it may be less expensive, and it may help physicians avoid costly medical errors due to misdiagnosis.

- More options for underserved areas. There are many places around the globe that do not have the right medical experts to treat certain conditions. Crowdsourcing can provide a mechanism for diagnosis in the absence of specialists.

- Speedier diagnosis. For difficult cases, a quick diagnosis may save spare the patient additional expense and unnecessary suffering. It may also save the physician unnecessary work and could save money for insurance companies.

- Speedier data collection and analysis. Crowdsourcing has been used to collect health care data and identify trends much quicker than could be done using traditional methods. This could lead to more effective treatments and greater accuracy in public health information.

- Additional income for physicians. When reimbursed at a fair level, physicians could add another source of income that may offer an equivalent or better return than seeing patients in person.

Drawbacks of crowdsourcing:

- Crowd adequacy. The crowd may not have the appropriate qualifications. Even if they do, the crowd may not have enough information to provide a response with any degree of certainty, causing inaccurate or incomplete results. This problem is being mitigated via ranking systems, qualification requirements, moderators, and the ability of the crowd to seek further information before responding.

- Physician mistrust. Crowdsourcing results may not be respected by the patient’s physician and could lead to resentment if these mechanisms are reimbursed similarly to the physician’s own services.

- Legal concerns. Medical crowdsourcing has the potential to violate health privacy laws. There is a high potential for data breach. The crowd or service could be liable if it provides an incorrect diagnosis that causes harm to the patient. If a physician acts on a crowdsourced diagnosis, does malpractice insurance cover any adverse outcomes? There are a whole morass of legal issues that might need to be resolved before crowdsourcing could be widely implemented. For now, it appears that these services simply have a robust waiver the patient signs before participating.

- Inequality concerns. Although many services are crowdsourced blind, there may still be some discrimination that affects these services. Some conditions that are more attributed to minority populations may receive less attention from the crowd. Provided demographic information like gender and age may cause some bias from the crowd. There is a chance that these issues would be less pronounced in a crowdsourcing environment than in a traditional physician environment. Further, concrete data would be available to determine whether the crowd is less successful at diagnosing certain groups.

- Inequality concerns, part 2. The financial structure of these services falls into one of two camps:

- Lottery winners. Dr. Sanders selects cases from many applicants seeking help and is sure to find a good solution for the lucky selectees. All other patients are simply out of luck. This inequality also applies in cases where underdeveloped areas are selected for a test program using these techniques.

- Pay-to-play. CrowdMed promises more attention and higher-rated detectives depending on how much money you contribute to your own diagnosis. This system will work a lot better for patients with the means to seek the top tier of diagnosis.

Insurance, if universal coverage were a reality, might equalize costs—but fair

compensation would need to be determined.

Where We Are Headed

To Physicians:

This is a new world that may seem loose and uncertain after the rigors of your own training. You need to decide whether to participate. If you are unable to diagnose your patient, will you consider a crowdsourcing method? If a patient arrives with a printout of likely diagnoses from these services, will you consider the suggestions?

By what process will you validate crowdsourced diagnoses? You have to decide how to determine the legitimacy of the crowdsourcing service used. Should you vet each service yourself or rely on industry recommendations? How should these services be vetted—by the underlying credentials of the crowd? By the probability that results are accurate? What should that success threshold be?

Are there any processes that could be reliably crowdsourced? Do you work in an underserved region that might benefit from quick diagnosis from a crowd for certain conditions?

Finally, you must decide whether you will participate as part of the crowd. Do you enjoy the detective work involved in diagnosis? What is reasonable compensation for your participation? Does participating in crowdsourcing (with the subsequent feedback of correct or incorrect diagnosis) help you hone your diagnosis skills?

To Insurance Companies and Actuaries:

This is a new world that feels fraught with risk. You must decide whether to offer crowdsourcing as a benefit to members. The initial question is, is this a cost-effective service to offer members? This question requires further studies. What is the annual cost of your members with symptoms, but no diagnosis? What is the cost for members with the same symptoms with a diagnosis? Alternately, you could look at costs for members before and after their diagnosis. How long does diagnosis usually take? How long would a crowdsourcing solution take? Could it lead to more claims if the member does not have an appropriate physician or care manager guiding them through their list of diagnoses? Would members use the service for every ache and pain, possibly leading to overuse? If so, what gatekeepers need to be put in place before these services are encouraged?

Are there members in your database who could benefit from these services right now? Should you flag them and reach out? How do you identify these members?

How would compensation for these services work? Would it be covered like a second opinion, or a new category entirely? Should a member copay be included to prevent overuse? Should you incentivize your in-network physicians to participate as a medical detective?

Would offering coverage for crowdsourcing invite lawsuits? There are numerous gray areas where the insurance company might have concerns about being sued by the crowdsourcing services, by physicians, and by members. These might include contracting and compensation fairness, appeals to cover these services from members, and requests for records that would then be shared with the crowdsourcing solution.

Conclusion

Crowdsourcing combines the difficulties of medical thought work and the technological gains of being able to communicate with experts around the globe. It is one of many exciting applications of our more-connected world.

Based on the potential gains, and when appropriate guardrails are in place, it could be a useful part of the health care system in the U.S.—if insurance companies and physicians are willing to embrace it. If either of these parties is not in agreement, then it will be very difficult both to pay for the services and to follow up on crowdsourced recommendations.

When the crowd is appropriate and appropriately incentivized, then we have found a useful pathway for patients without a clear diagnosis. Further, crowdsourcing provides new avenues for enhanced research, accurate surveillance, and improved public health. Based on the initial review and the favorable outcomes reported, crowdsourcing of medicine seems to me like it is here to stay—doctors, insurance companies, and actuaries would be wise to consider the emerging questions about this promising practice now.

ANDREA HUCKABA ROME, MAAA, FSA, CERA, is vice president at Lewis & Ellis, Inc.

References

[1] www.crowdmed.com.

[2] Juusola JL, Quisel TR, Foschini L, Ladapo JA; “The Impact of an Online Crowdsourcing Diagnostic Tool on Health Care Utilization: A Case Study Using a Novel Approach to Retrospective Claims Analysis”; J Med Internet Res 2016;18(6):e127.

[3] Wazny, Kerri; “Applications of crowdsourcing in health: an overview”; Journal of Global Health vol. 8,1 (2018): 010502. doi:10.7189/jogh.08.010502.