By Joe Allbright, Jonathan Callund, Andrea Cardoso, Jac Joubert, Walter Marsh, and Susan Mateja

Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a series of articles from the Health Practice International Committee on ideas from foreign models of health care that may assist the United States in finding cost-effective ways to deliver high-quality health care in an equitable and sustainable way.

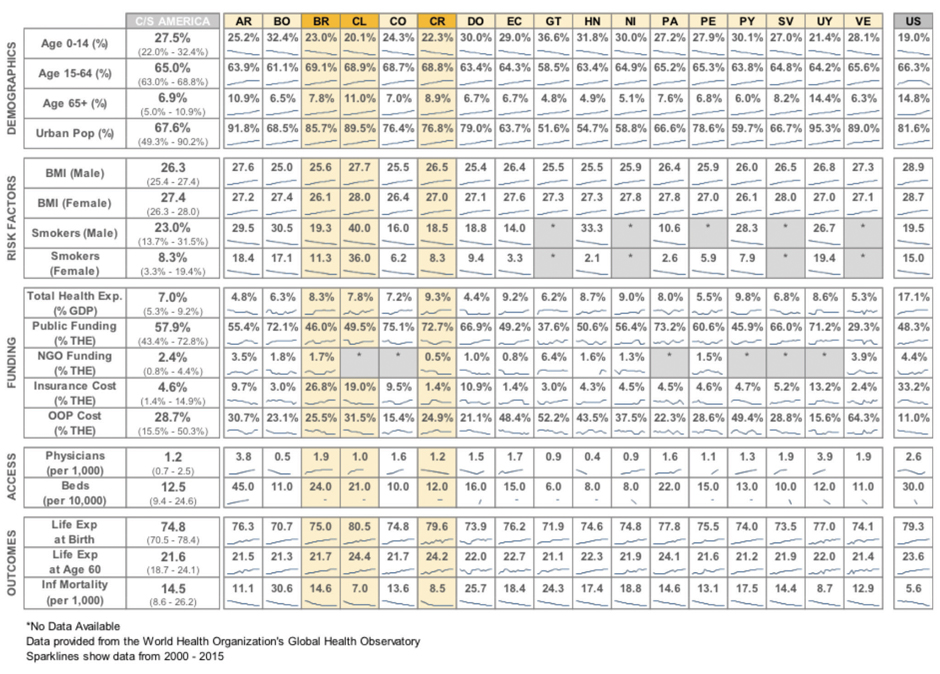

The nations of Central and South America vary widely in the size of their economies, the structure of their governments, and their perspectives on market-driven reforms versus social programs. Many, though, face similar challenges in providing health care: designing a system to work in an environment of significant income inequality; structural and geographic barriers to care in remote areas; the prevalence and emergence of communicable diseases; and the growing need to support the chronic illnesses of an aging population. In the following we detail how three countries in the region have approached health care.

Brazil

Health care in Brazil is a protected right; the constitution states: “Health is a right of all and an obligation of the State.” However, delivering health care on an equitable basis to all in the country is complicated by a number of dynamics. Brazil is a geographically expansive country, which presents challenges in health care access and infrastructure. Brazil has to deal both with infectious diseases, which have been the traditional driver of health care costs, as well as rapid growth in non-communicable diseases associated with lifestyle changes. Like many other nations across Central and South America, Brazil’s high level of income inequality requires a health system that can serve a financially and educationally diverse population with a wide range of care needs.

To deliver on the constitutional promise, the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) was founded in 1990. The SUS is a public delivery system funded through municipal, state, and federal taxes that provides universal health care access, free of charge, to all individuals.[1] One of the unique features of the Brazilian system is the Family Health Strategy, an approach to extend the reach of providers by supplementing the core primary care team of a physician and nurse with community health workers (CHWs). CHWs visit families on a regular basis and provide routine services such as medication monitoring and chronic disease management, health education, and pre- and postnatal care. Some 67 percent of Brazil’s population is served by 265,000 community health workers, who visit each household at least once a month. In addition to health education and monitoring, the CHWs also support infectious disease monitoring and prevention.[2]

Through the SUS and the Family Health Strategy, Brazil has seen dramatic improvements on a number of measures of national health. Between 2000 and 2015, life expectancy climbed from 70.5 years to 75.0 years and infant mortality was nearly halved.[3]Nonetheless, many Brazilians feel the SUS does not provide the level of quality and access they would like, citing issues of waiting times, travel times, availability of equipment, and choice.[4] In rural areas, access remains a particularly acute need even for primary care, which has led to the government investing in additional programs to draw more doctors to these areas. In urban centers, a number of private clinic-based and concierge-type provider solutions have sprung up to address the demand for care, providing enhanced access with reduced wait times.

While the SUS serves as a universal safety net, many Brazilians aspire to have private health care. With approximately 25 percent of the population (more than 50 million individuals) with private health coverage, Brazil is the world’s second largest private health insurance market after the United States. Private health coverage in Brazil is defined loosely as either “health plans” or “health insurance.” Health plans are closer to the United States’ HMO model, providing comprehensive coverage within a network of providers and within a specific geographic area with limited ability to select a provider. Health insurance is closer to a PPO model, providing a wider selection of providers and increased cost sharing, with lower associated premiums. The vast majority of private health coverage is employment-based coverage. High levels of regulation in the individual market, coupled with very consumer friendly interpretations of contract language by the judiciary, has affected the individual market negatively. Cost pressures remain, with increases in both premiums and out-of-pocket costs.

Chile

Chile’s health care structure is both private and public. The public system, currently financed and administered by Fondo Nacional de Salud (FONASA), was introduced in the 1950s. A second option was introduced in 1980 with the creation of the Instituciones de Salud Previsional (ISAPREs)—private sector health insurers who compete for employees’ social security health care contributions. As of December 2016, there were 13 for-profit ISAPREs that cover 3.4 million individuals (19 percent of the Chilean population), while FONASA covered 13.5 million individuals (76 percent). The remaining 5 percent of the population comprises the armed forces, which are covered under autonomous programs, and those without health insurance.

All employees and retirees in Chile are required to contribute 7 percent of their income (up to the social security ceiling) to health care coverage, which is collected as a pre-tax deduction from payroll. A member can decide whether this contribution will go to FONASA or to one of the ISAPRE insurers. Enrollment covers both the employee and his or her legal dependents. In the case of FONASA, there are no additional premiums. A direct government subsidy covers FONASA enrollees who are unemployed. Members of ISAPREs, however, may pay additional premiums on top of the minimum contribution to obtain a richer plan and/or coverage for additional family members. Unlike the 7 percent health contribution, these additional premiums are not on a pre-tax deduction basis.

Click to enlarge

FONASA has two means of offering health care access: an “institutional care” option that provides access to the public hospitals and providers and a “free choice” option that allows access to participating private providers. Depending on their income bracket, member cost sharing may be zero or 10 percent or 20 percent of costs. The ISAPREs offer a number of individual plans with a wide range of benefits tailored to the ages and family profiles of the members. All the ISAPREs offer their members access to closed preferred-provider networks with lower prices, often ensuring zero co-payment.

The ISAPREs system was created to help Chile focus its resources on the poorer segments of the population, leaving those able to provide for themselves to do so. The result has been segmentation of the population by income, age, and health status. The contributions to FONASA are the same 7 percent for all working individuals, while an ISAPRE may vary premiums to account for an individual’s risk based on age and sex. FONASA is state-funded when members are unable to contribute, whereas an ISAPRE is not. As a result, the ISAPRE system attracts the young, healthy, and more affluent, while the FONASA system covers an older and lower-income population. Over half of FONASA funds come from state subsidies rather than direct contributions.

The ISAPREs system was created to help Chile focus its resources on the poorer segments of the population, leaving those able to provide for themselves to do so. The result has been segmentation of the population by income, age, and health status. The contributions to FONASA are the same 7 percent for all working individuals, while an ISAPRE may vary premiums to account for an individual’s risk based on age and sex. FONASA is state-funded when members are unable to contribute, whereas an ISAPRE is not. As a result, the ISAPRE system attracts the young, healthy, and more affluent, while the FONASA system covers an older and lower-income population. Over half of FONASA funds come from state subsidies rather than direct contributions.

Chile’s health care system continues to evolve. In 2005, the Explicit Guarantee System (Acceso Universal con Garantías Explícitas, or AUGE) was established to ensure that all Chilean residents have access to timely treatment of necessary conditions. This has been the most important health care initiative in the country over the past two decades. Under this program, health care problems were ranked and protocols were developed to ensure standardized parameters for treatment, wait times, and out-of-pocket costs. The AUGE system places the obligation on both FONASA and the ISAPREs to ensure timely delivery of high-quality services for the 56 conditions outlined in the original legislation, which subsequently have been expanded to 80 conditions.[5]

Costa Rica

The constitution of Costa Rica defines workers’ protection against the risk of illness through social insurance as an inalienable right. Costa Rica has made strides in achieving universal health coverage, increasing the insured population from 87.6 percent in 2008 to 94.7 percent as of 2014.[6]

Costa Rica has a two-tiered health system; both a public and private sector system. The Ministry of Health governs both sectors, setting national policy on health care planning and promotion. The Ministry of Health delegated to the Costa Rican Social Security Administration (CCSS) the activities of prevention, recovery, and rehabilitation. Within the public sector, the CCSS administers direct employer-employee relationships and insurance for self-employed individuals, pensioners, the indirectly insured (family members and relatives), and those insured directly by the state. Health care is delivered in a standard, integrated fashion for each of these groups through the Equipos Básicos de Atención Integral en Salud, or EBIAS, which are primary care centers, clinics, or the national hospitals.

The public health care system is financed through a fund created by tripartite contributions based on workers’ salaries: Employers contribute 14.16 percent of salaries, representing about 62 percent of the fund; workers contribute 8.25 percent of their salaries, representing 36 percent of the fund; and the state contributes 0.5 percent of salaries, for about 2 percent. Private insurance is provided by five insurance companies, cooperatives, and self-management companies. Private medical services, private clinics, and private hospitals are available under this sector. The private sector is currently small, only representing about 2 percent of total health expenditures in 2014, but it is growing. Already this has put a strain on the public sector system as high-income individuals opt out of the system and their salaries aren’t included in the funding of the public sector system.

The cooperation of the Ministry of Health and the CCSS has created institutional stability around financing and planning as well as a well-differentiated provider arm with strong primary care at its base. The structure lends itself to effective dialogue between users of health services and managers to drive improvements at the local level. The collaboration promotes innovation and has contributed to raising the life expectancy in Costa Rica to 79.9 years, close to the OECD average of 80.6.

Costa Rica’s health care system is facing some challenges, however. While successful in controlling communicable diseases, as in many emerging economies there are rising rates of circulatory diseases, cancer, and diabetes that threaten the general health of the population. An increase in longevity coupled with a decrease in fertility had led to a smaller percentage of the population contributing to the health care system. Funding concerns are exacerbated further by constant migrant flow and increasing medical facility and personnel costs. There is dissatisfaction with the public system stemming from long waiting periods and lapses in the quality of services, creating a demand for private insurance among mid- to high-income individuals.[7]

Lessons for the United States

Brazil offers a number of lessons for the United States. Brazil illustrates the value of a universal public safety net in improving the health of the population, while also providing some indications of the limits of a public system in a geographically and financially diverse country. It provides a unique mechanism whereby private providers and insurers supplement government programs. The CHW program demonstrates a way to foster human-centric care and extend health care access. Brazil also provides evidence of the negative effect of lifestyle changes on health care costs and the need for wellness and prevention activities.

Chile’s experience has shown that regulated private insurers can work effectively alongside a public system to deliver competitive, high-quality services to a large segment of a population, offering overflow services to public system users when required. It also highlights the challenges of merging short-term incapacity/sick-pay coverage with the funding of preventive and curative medical care. The implementation of a system of major medical expense guarantees also has had a positive effect in both the public and private sectors.

Costa Rica provides an example of a highly integrated delivery system across three distinct levels of coverage. This integration of health care levels is a key component of sustaining universal health care. Costa Rica has embraced the notion that all people should receive appropriate care at an affordable cost. To achieve this, there must be equality between the public and private systems. There is a risk of a self-perpetuating cycle, however; if quality concerns drive wealthy individuals to a private market, the result will be less funding for the public sector and further reductions in quality.

THE AUTHORS are members of the Academy’s Health Practice International Committee.

Endnotes

[1] James Macinko and Matthew J. Harris; “Brazil’s Family Health Strategy—Delivering Community-Based Primary Care in a Universal Health System”; New England Journal of Medicine; June 4, 2015.

[2] Hester Wadge et al.; “Brazil’s Family Health Strategy: Using Community Health Care Workers to Provide Primary Care”; The Commonwealth Fund; December 13, 2016.

[3] World Health Organization; “Brazil: WHO Statistical Profile”; January 2015; http://www.who.int/gho/countries/bra.pdf.

[4] Célia Landman Szwarcwald et al.; “Perception of the Brazilian Population on Medical Health Care”; Ciência & Saúde Coletiva; February 2016.

[5] Thomas J. Bossert and Thomas Leisewitz; “Innovation and Change in the Chilean Health System”; New England Journal of Medicine; January 7, 2016.

[6] Maria del Rocío Sáenz, Juan Luis Bermúdez and Mónica Acosta; “Universal Coverage in a Middle Income Country: Costa Rica”; World Health Organization; 2010.